1930s L.A. Illustrated: Angel's Flight, the Old Plaza, A Secret Garden and More

In November 1935, Los Angeles Times reporter Timothy Turner and staff artist Charles Owens began a year-long ramble through the historic core of downtown. The Times — better known for boosting suburban real estate and denouncing unions — published more than 40 vignettes of the city's aging Victorian mansions, derelict theaters and other survivals of the 19th century. Owens illustrated them with evocative pencil sketches.

Turner had worked the "hotel beat," a long-ago newspaper assignment that covered the comings and goings of notable guests to the city's hotels. Turner remembered the hotels when they were at their grandest. He worked those recollections into his essays when the guests were mostly tired old men.

Owens was a mostly self-taught artist who had joined the Times in the 1910s. He was best known for full-page drawings of the huge projects of early 20th century Los Angeles: dams, highways, bridges and harbors. But for Turner's pieces, the view is almost always intimate and often impressionistic. Owens remembered what an art director had told him early in his career, "A pencil moved by a man's heart can catch life that no camera will ever see."

Turner's brief essays are sometimes condescending to the marginalized men and women making a hard life in Depression-era Los Angeles, but the best of his pieces have the wistful gentility of an essay by Joseph Mitchell, who wandered in — and wrote wisely about — the nondescript parts of New York in the 1930s.

Finding Stories

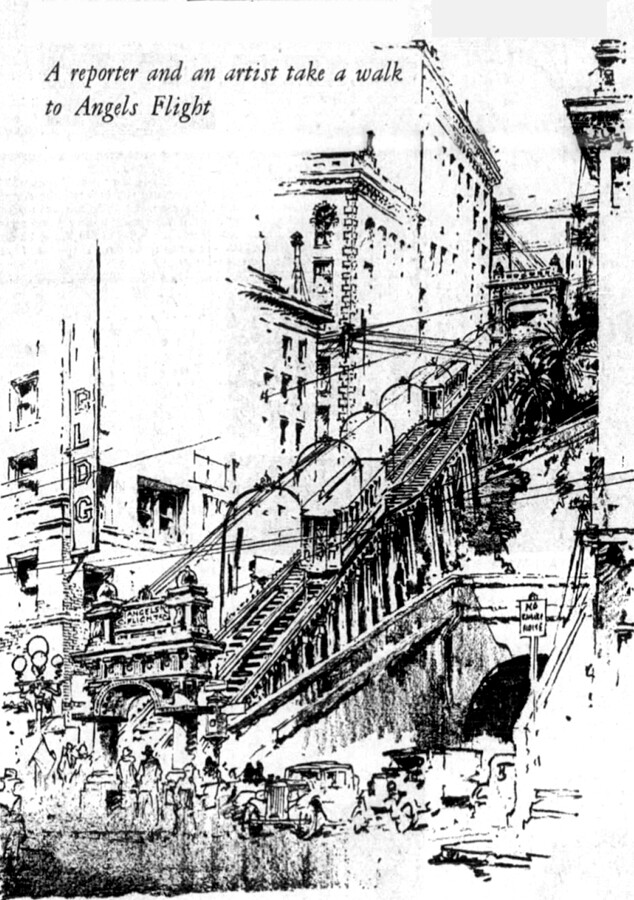

Reporter and illustrator didn't stray far from the Times building on Spring Street. Just as Instagramming tourists do today, Turner and Owens stopped at the Angel's Flight funicular that still carries riders to the top of Bunker Hill. Turner wondered why downtown ignored its stately hill, which he thought should have had the apartment buildings and hotels that crowned San Francisco's Nob Hill.

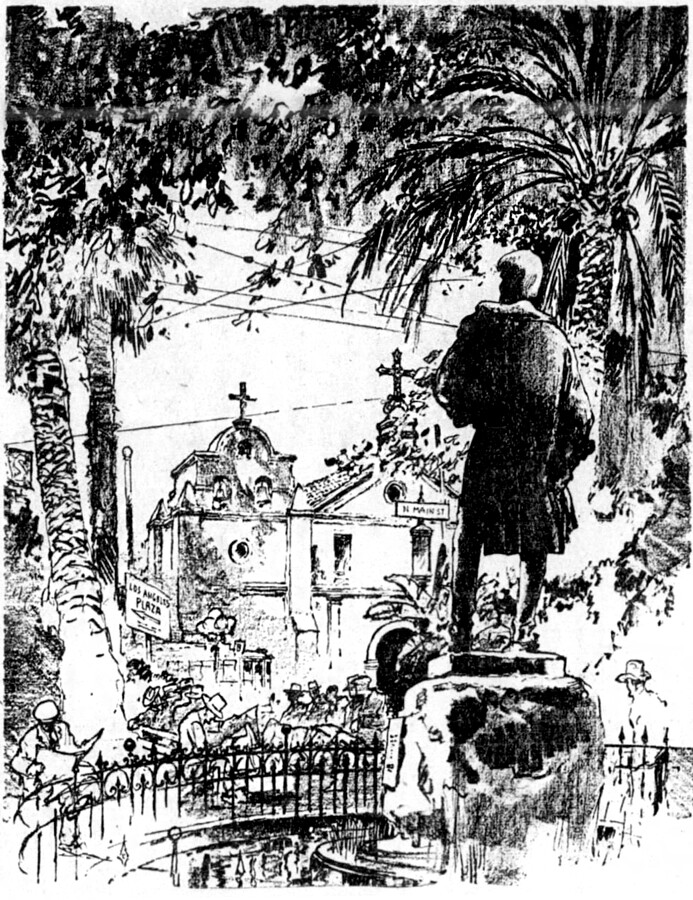

Later, Turner sat among Latino laborers in the old plaza and listened to their conversations. He preferred their company to the Anglo haranguers of Pershing Square. "Everybody minds his own business in the Plaza, one of the few places in town where this quaint old notion holds sway."

Turner found his stories in what he called Old Town. Much of what he saw and Owens illustrated was on the cusp of demolition. Los Angeles was modernizing, erasing the past and, Turner thought, something of its urban life.

Turner watched as one of the last games of rebote (handball) was played against the side of the Pyrenees Hotel at Aliso and Alameda streets. Rebote is the simplest form of the sport. All that's needed is a rubber ball and a wall. The side of the hotel had been that wall for 60 years. "Sixty years is a long time," Turner wrote, "for anything to be done in the same place in a … city that is supposed to be new. But now no longer will the balls bang against the wall of a Saturday or Sunday or saint's day."

Even as the ball smacked high on the wall in Owens sketch, the old hotel was being taken down to clear the way for Union Station.

Secret Garden

Turner also wandered into the former Masonic Hall next to the Pico House at the old plaza. The ground floor had become a barbershop and a Mexican café; upstairs was a sign painter's shop with a wrought-iron balcony overlooking the street. "One can stand on the little balcony … and look up and down Main Street, once Calle Principal," Turner wrote. "It is a good view into the past, into Los Angeles as it was, almost without a detail of change, forty, fifty, sixty years ago."

In his encounters with places like the Masonic Hall, Turner recovered a city that moved more slowly, that grated less on his ear, that still had gracious things if you went looking for them. Among the places Turner visited, the Masonic Hall is one of the few that still remain. Today, it's part of El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument.

Other places were harder to find. "One must go up alleys and through the back doors of little shops to find many things, now curious, now beautiful, in Old Town," Turner advised his readers.

One of those beautiful things was behind a flower shop on San Pedro Street just north of 1st Street. Mr. Toyo Y. Maeda, the shop's owner, had cleared part of a parking lot and laid out a Japanese garden. "You can stand there right in the heart of old Los Angeles, with streetcars and motor trucks jammed on all sides, and hear birds sing and look up at the blue square of sky and write a poem or … commune with nature, according to your desires."

Owens' drawing shows the garden's torii gate, a bridge over the koi pond and the tea pavilion beyond.

Toshiyuki and Chiharu Okamura purchased the Toyo Florist and Nursery in 1940. In early 1942, the Okamuras lost their home and their shop and were forced with their three children into the Manzanar internment camp, along with thousands of other Japanese Americans.

The garden is gone now, replaced by a sunken parking lot and a plaza that honors the Reverend Noboru Toriumi, a Little Tokyo community leader. "Sweeps" of Toriumi Plaza since 2020 have periodically removed encampments of homeless Angelenos.

Places of Memory

Turner's fondness for places of memory led him to devote a year to just looking around. In a Times profile in 1936, Turner said he had no other reason except he wanted to do it.

The Times offered its own reasons in an editorial note that headed Turner's first essay. Turner and Owens, the Times wrote, had "an eye for romance in the commonplace" and for "landmarks almost forgotten in the march of progress." These sketches and the stories "may be the only record left of many interesting and curious things."

Nostalgia for "interesting and curious things" wasn't the Times' usual editorial position. Perhaps the paper (which did so much to make Los Angeles a "city of tomorrow") reacted to the onrush of modernity, symbolized by Union Station, or by the mere fact that much of old Los Angeles was about to be covered by the station's tracks and parking lots.

It is a good view into the past, into Los Angeles as it was, almost without a detail of change, forty, fifty, sixty years ago.Timothy Turner, on Los Angeles' Main Street circa 1935

There's something deeper in Turner's stories—a realization that his sense of place was at risk because of unstoppable progress, that he would soon have only memories of the things that made the past real to him. Owens and Turner represented a generation of Angelenos (Turner was 51, Owens 55 in 1936) who would grow old in a post-war "city of tomorrow" that would have little interest in the modest landmarks Turner's words and Owens' pencil brought to life.

Sources

Turner's "Rediscovering Los Angeles" essays and Owens' illustrations are behind a paywall at Newspapers.com.