Should California's El Camino Real Become a UNESCO Landmark?

It’s been called the “Royal Road of the motor tourist.” The El Camino Real, in current times, stretches from San Diego past Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, all the way to San Francisco and Sonoma, meandering along well-known modern highways. In Spanish colonies, historians say, since everything was owned by the king of Spain, the roads would have been considered royal.

More on El Camino Real

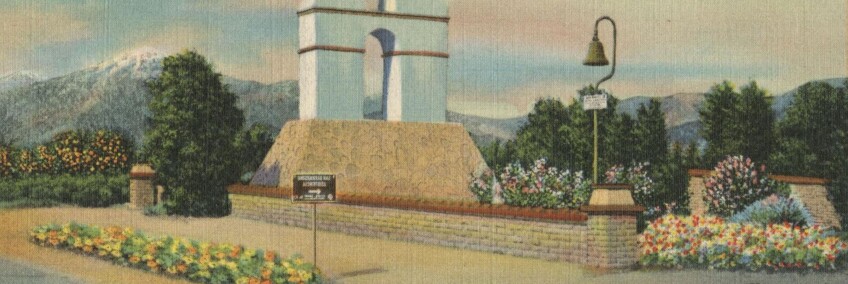

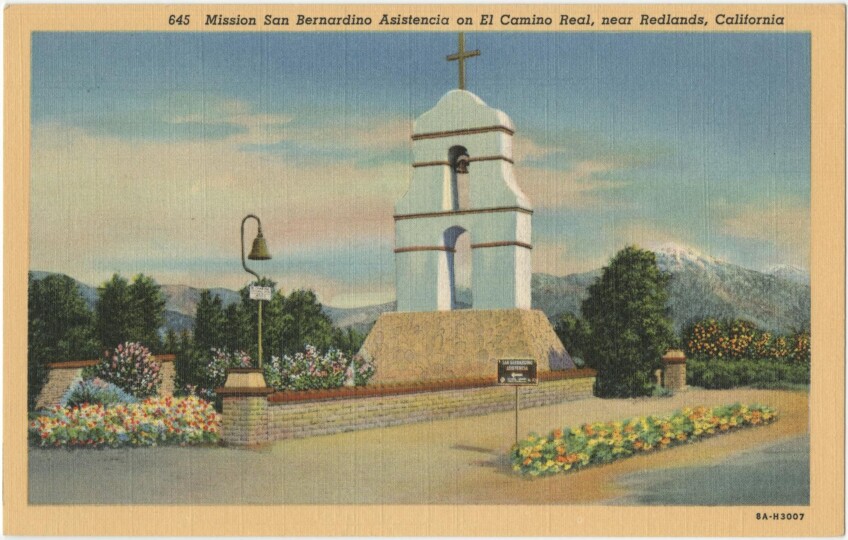

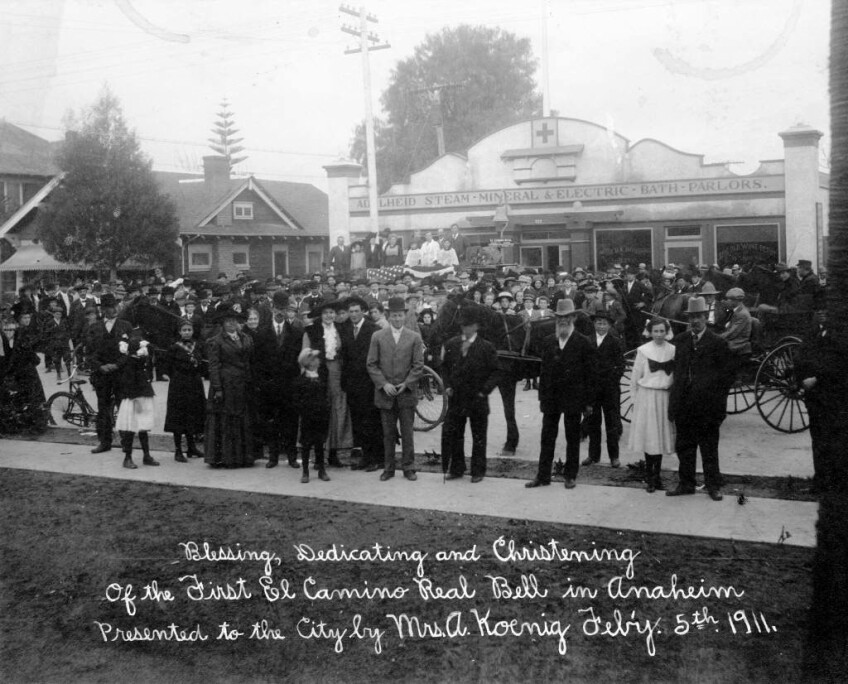

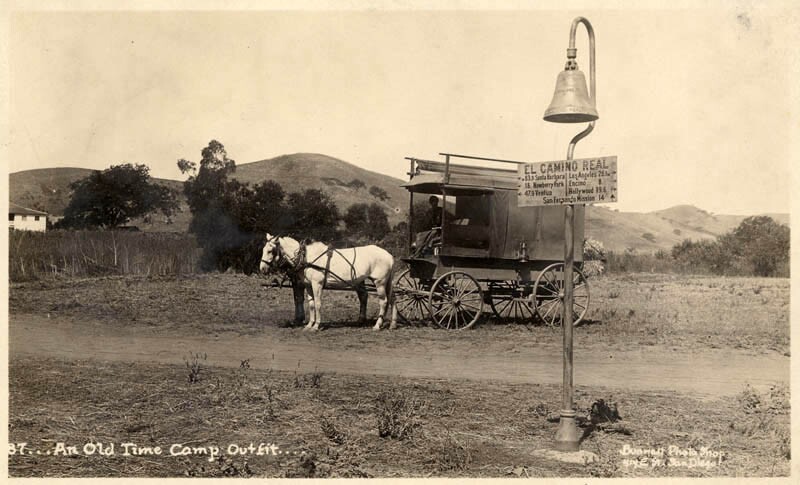

The road connected 21 missions up and down the coast of Alta California. In the 1900s, the Camino Real Association began to mark the road with replica mission bells, which it placed along the highway.

El Camino Real is as much part of California’s history – echoing a time when missionaries spread the word of God to native Californians – as it is a modern myth, a romanticized relic from the past that was reimagined in the 20th century as a way to boost tourism and entice people to travel.

Since last year, the California Missions Foundation, along with Mexico-based Corredor Histórico CAREM, A.C., is looking to designate the El Camino Real as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site. The foundation is dedicated to preserving the landmark California missions. The plans for this multi-year, multi-national initiative include partnering with government agencies in both the U.S. and Mexico, as well as California State Parks, the National Parks Service, Native American groups, and other organizations.

World Heritage designation by UNESCO signifies that a site possesses special cultural or physical significance. There are nearly 1,000 designated sites worldwide, including 33 in Mexico and 23 in the United States – and, in California, places like Redwood and Yosemite national parks.

Ty Smith, chair of the California Missions Foundation, said the foundation is a diverse organization that seeks to be inclusive and respect a variety of opinions. He said no formal application has been submitted to UNESCO, adding it’s a multi-year process. The designation includes not only the El Camino Real but also the 21 missions; the presidios, or fortified military bases; and many of the key pueblos, or civil settlements that Spain founded between 1769 and 1823. He said the route is still being shaped.

“It is important to understand the camino not as the highway that it is today, but as a historic corridor that connected the people and places of early California,” he said. “We are in the exploration phases...what is this corridor and what does it mean then and now? The designation is not meant to celebrate the colonial past, but represents an effort to shed light on the camino’s complex and important history. At the moment, we are gathering input and thinking of the best way to frame the corridor concept.”

Smith said for many folks, a designation would be helpful in driving international tourism to the various sites. He said a lot of historians understand the El Camino Real as a “braided corridor” that wasn’t just one route but many. He said when people hear “El Camino Real,” they envision Highway 1 or Highway 101 and each mission being located exactly a day’s travel apart.

“That’s all part of the mythology but at the same time having a broader perception of that corridor, that movement of people, has a longer history than even the missions,” he said. “It was a colonial project that included presidios, pueblos and to understand it wasn’t just a land route, there is a maritime component to talk about.”

Like Smith, some historians have said the El Camino Real is a myth, it doesn’t exist nor did it ever exist dating back to the colonial period of California’s history.

During the colonial period, maritime transportation was far more important than over land transportation, according to historian Matthew Roth of the Automobile Club of Southern California Archives.

“How much did overland transport matter in the mission period? Given the inferential questions about the colonial period, I still think the way it became of the central part of the projected culture of Southern California in the early 20th century was significant,” Roth said.

He said the question becomes “who thought this road was important and then there’s a pretty clear answer.”

The answer lies in the early 20th century and the booster period, or when tourism became popular in Southern California.

“Another aspect of this boosterism is ‘come to Los Angeles’ and the question is why? What’s the story they are telling? Part of it is around the climate and there’s a whole genre on America’s Mediterranean shore,” Roth said.

When the request came from the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West, a group dedicated to historic preservation within the state, in 1907, the Auto Club was just beginning to post directional signs on the region’s highways, the first activity that required paid staff rather than volunteers, Roth said.

“Plus the Auto Club paid for the signs themselves. They were in the early stages of working out how to do all that without over-committing the organization, and I think that was behind the decision to decline participation in the bell project,” Roth said. He said the club did agree to maintain the bells.

As to whether the road should be designated as a UNESCO site, Roth said its association with the booster period – a significant historical episode in its own right – might be a reason enough to apply for a listing.

Phoebe S. K. Young, associate professor of history at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said she tackled the El Camino Real as a subject in her book “California Vieja: Culture and Memory in a Modern American Place” because it was an interesting opportunity to see how Anglo Southern California came to decide there was something interesting, valuable, and advertisable about the Spanish past.

“The El Camino Real is an example where you see the boosters saying, ‘No this is a good thing. Let’s advertise and talk about it,’” Young said. “It was an opportunity to see how Anglos were shifting the Spanish past in the working out of this road and what it meant and how to align what they found interesting from the history with modern needs – in this case, the automobile.”

She said there is a period in history where the road is forgotten but it’s re-popularized during the early 20th century.

“From there it became lobbying from different towns because it would bring more people to their town,” she said of the El Camino Real. “All this to say they knew they were making up the route as they best they could, subject to a variety of modern factors as well as historical research. … It made sense other than the fact they were trying to present it as an authentic road.”

Romantic Notions

Steven Hackel, professor of history at the University of California at Riverside, agreed that El Camino Real was a 20th century reinvention. There were roads in 18th-century California, but the romantic notion of one single camino is not historically accurate, he said.

“To many people a UNESCO World Heritage site recognition, by definition, is a statement that what happened in a place was positive and good and represents the highest ideals of western civilization. But this is not necessarily the case,” Hackel said. “UNESCO has recognized places that were instrumental to the transatlantic slave trade because it considers those places to be exemplary as sites of human tragedy and loss.”

He said “there was no ‘El Camino Real’ [in California] as there was in New Mexico.”

“Supplies came by sea, not by land,” he said. “It’s difficult to talk about something that didn’t exist. It’s a fiction created in the 20th century to promote automobile tourism up and down the coast of California. When people think of the El Camino, they think of the King’s Highway from Mexico City to all these borderlands, and that didn’t exist in California.”

Jim Sandos, Farquhar Professor of the American Southwest at the University of Redlands, recalled how Junipero Serra, who established the missions as colonial religious institutions, said was a priest could spend every third night in a mission along the trail and the missions were not built one day apart.

“There’s no one single road that connects them all,” Sandos said. “Missions were being built, hop scotched all over, they were not sequential.”

Smith, of the California Missions Foundation, said the reason one should restore and maintain the missions, not in spite of the fact they represented unhappy places for native people, but because of them.

“The reason we should maintain them [the missions] is to tell a native American story. Native Americans lived there and we should tell their stories. That is part of the complexity that a World Heritage Site designation would shed light on. The reality is to maintain the historic place, you need people to visit them so they understand them, care them and protect them.”