Shootout at Temple & Main: The LAPD’s Violent Beginnings

Will the Los Angeles Police Department ever outgrow its violent origins?

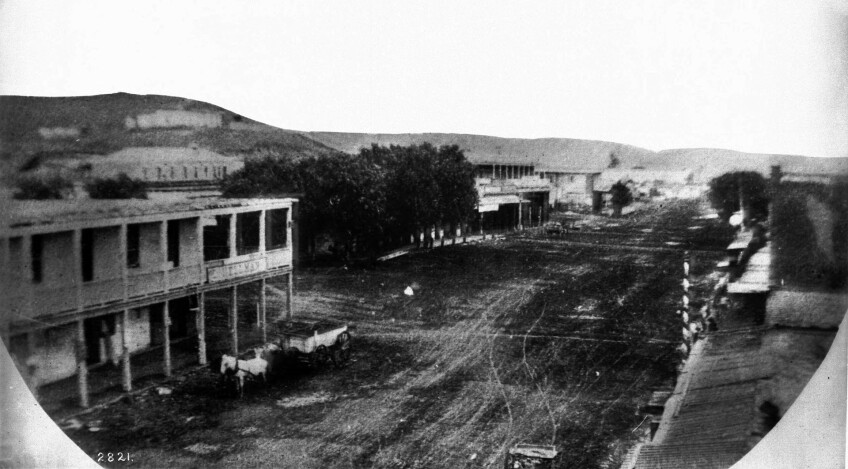

Los Angeles during the mid-nineteenth century was described by an early city historian as “undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation.” This notoriously violent town of only a few thousand residents boasted a much higher murder rate than New York, Chicago, or San Francisco. Horace Bell, an early chronicler of the city, stated: “Human life was about the cheapest thing in Los Angeles and killings were frequent.”

The lawlessness extended to the town’s law keepers. Prior to the formation of a bona fide police department in 1869, “official” law enforcement in Los Angeles consisted of a county sheriff and city marshal. But they were often preoccupied with other duties – the sheriff with the collection of county taxes (out of which he took a share), and the marshal with the roundup and auction of so-called vagrant Indians (for which he received a commission). Stopping crime was a secondary concern. So Angelenos turned to volunteer groups and vigilance committees in an attempt to establish law and order. All too often, these volunteers become vigilantes and the committees would devolve into lynch mobs.

But the creation of a formal police force did not immediately bring effective law enforcement to the area. Much of the town’s violence and criminal activity, including gambling and prostitution, continued unabated.

And when it came to prostitution in the Chinese community, rather than trying to prevent crime, some officers actually aided and abetted the sex traffickers. In fact, a profitable business dynamic was created. When a Chinese prostitute ran away, the prostitute’s trafficker would file a complaint with the police, alleging that the prostitute had stolen something. American lawmen would locate and arrest the prostitute. The trafficker would put up the bail and the police would release the prostitute back into the trafficker’s custody. And, as a result, the American lawmen would receive a reward for their efforts.

This nefarious arrangement was in full swing on October 14, 1870, when a young Chinese prostitute named Sing Yu (also reported as Sing Lo or Lon You), ran away, possibly with a lover. Her sex trafficker filed a complaint with the police seeking her arrest. The complaint alleged that the missing prostitute had stolen a gold watch and $130 in gold coins. A $100 reward was offered for her return.

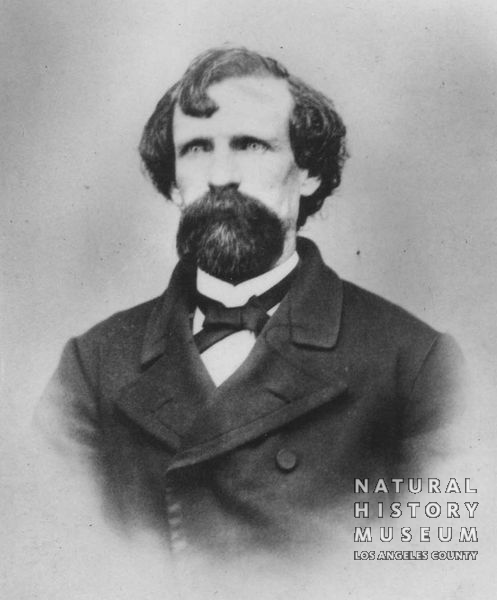

City Marshal William Warren and a hotheaded subordinate police officer named Joseph Dye, initiated separate, competing investigations to find Sing Yu. Warren located the girl first in San Buenaventura (Ventura) and brought her back to Los Angeles. While Warren had done the “leg work” and located the woman, Officer Dye thought he was entitled to the reward because he had telegraphed the warrant to the marshal of San Buenaventura, authorizing him to detain her.

Officer Dye was an impetuous and violent man and did not take defeat lightly. And this was compounded by the fact that this was not the first time that Dye had been bested by his boss. Just a couple months earlier, Warren had located a kidnapping victim before Dye and collected the reward. Joe Dye was not going to stand for it again.

So on October 31, 1870, Marshal Warren and another policeman were escorting Sing Yu back to jail when an angry voice called out from the crowd: “Warren, O!, Warren.” An enraged Officer Dye approached Warren and asked him about the reward money. Warren dismissed Dye saying that he did not want to have anything to do with him. That was not a sufficient response for Dye, who got even angrier: “Do you suppose I am going to get swindled out of my money. Sir, you have robbed me out of that money.” The two men now stood only a few feet apart. Warren, who was holding a derringer (a small, single-shot pocket pistol) behind his back, called Dye a liar and denied robbing anyone. At this point, the situation began to unravel.

Dye raised his cane as if to strike Warren. In response, Warren pulled the derringer from behind his back and fired. Dye jumped back and the bullet grazed his face. Dye dropped his cane and reached for a six-shooter under his coat. Warren dropped the derringer and reached for his six-shooter. Guns drawn, the two men started shooting. A few spectators were hit by the wild shots. Warren was hit in the abdomen and fell to the ground exclaiming: “I’m killed.”

Dye, who himself had been shot in the thigh, charged towards his wounded boss. Dye hit Warren in the head with his pistol, then grabbed him and bit a chunk out of Warren’s ear. Several men from the crowd had to pull Dye off of Warren. Warren tried to get up but his injuries were too severe. The bullet was lodged in his groin and it had pierced his bladder. He died the next morning.

The LAPD was born in a violent small town simmering with racism and the force reflected its mother city.

Dye was put on trial for Warren’s death, but he was acquitted on the basis of self-defense. Witnesses testified that Warren had fired first. Years later, Dye was shot and killed by a man he had threatened in connection with a dispute over money. Meanwhile, the prostitute, Sing Yu, was released for lack of evidence, and was taken back by her trafficker.

The shootout between Warren and Dye, which occurred near the present-day intersection of Temple and Main Streets (next to City Hall and a block away from the current LAPD headquarters) offers a glimpse into the lawless and violent early days of our city. In 1870, as it does today, the LAPD reflected the social and cultural environment of Los Angeles. The LAPD was born in a violent small town simmering with racism and the force reflected its mother city. As Los Angeles grew into a modern city, the LAPD transformed into a modern police department. But the city’s issues with race and violence continued to be manifested within its police department. If they were alive today, Warren and Dye would not be able to recognize their city or police department. But they would recognize the violence and racism that have continued to plague the city and its police force.

Sources

Los Angeles Daily News, November 1, 2, 1870.

Los Angeles Star, November 1, 2, 1870.

Faragher, John Mack. Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), 263-276, 467-468.

Hays, Thomas. Los Angeles Police Department. (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

Newmark, Harris. Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913 (New York: The Knickerbocker Press), 418.

Secrest, William. California Badmen: Mean Men with Guns. (Sanger, CA: Word Dancer Press, 2007), 148-160.

Zesch, Scott. The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 70-75.

“History of the LAPD.” Los Angeles Police Museum. Accessed September 21, 2016. http://www.laphs.org/history.html

“History of the LAPD.” Los Angeles Police Department. Accessed September 21, 2016. http://www.lapdonline.org/history_of_the_lapd/content_basic_view/1107

Top image: Portrait of the Los Angeles Police team, posing with rifles, 1890. Courtesy of the USC Libraries – California Historical Society Collection.