Shindana Toys: Dolls That Made a Difference

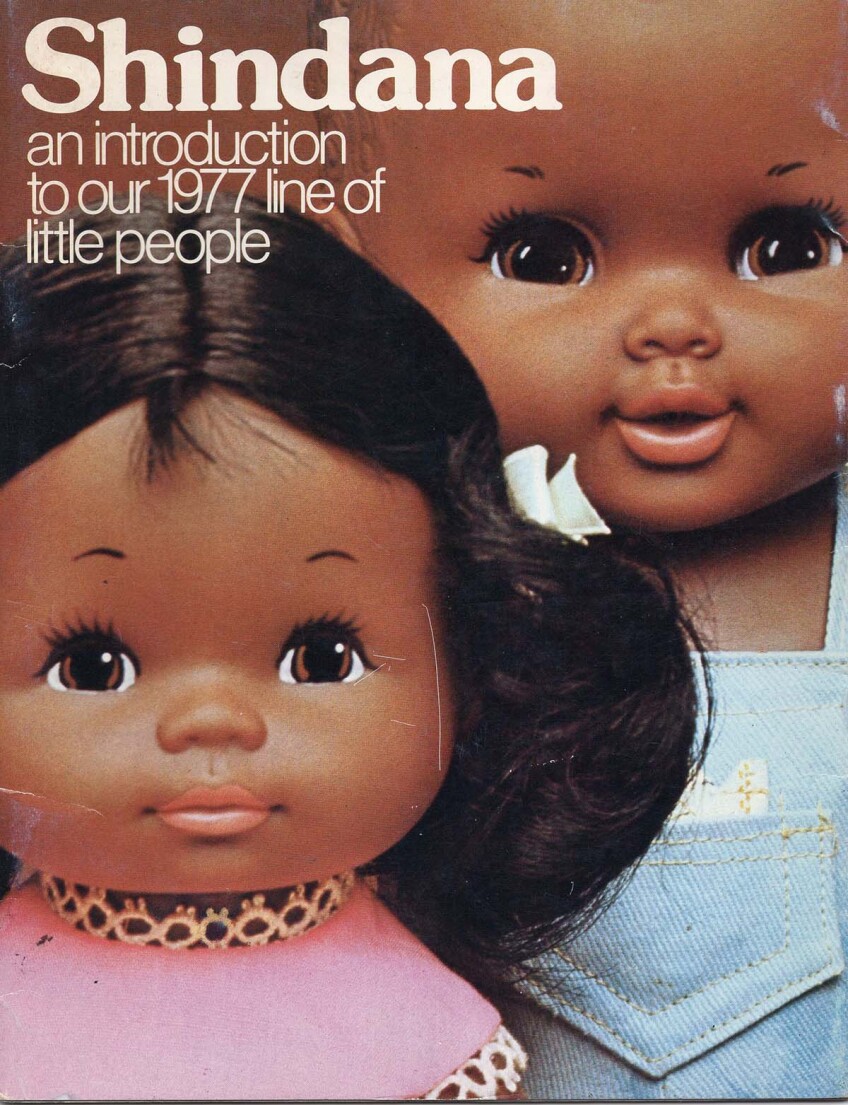

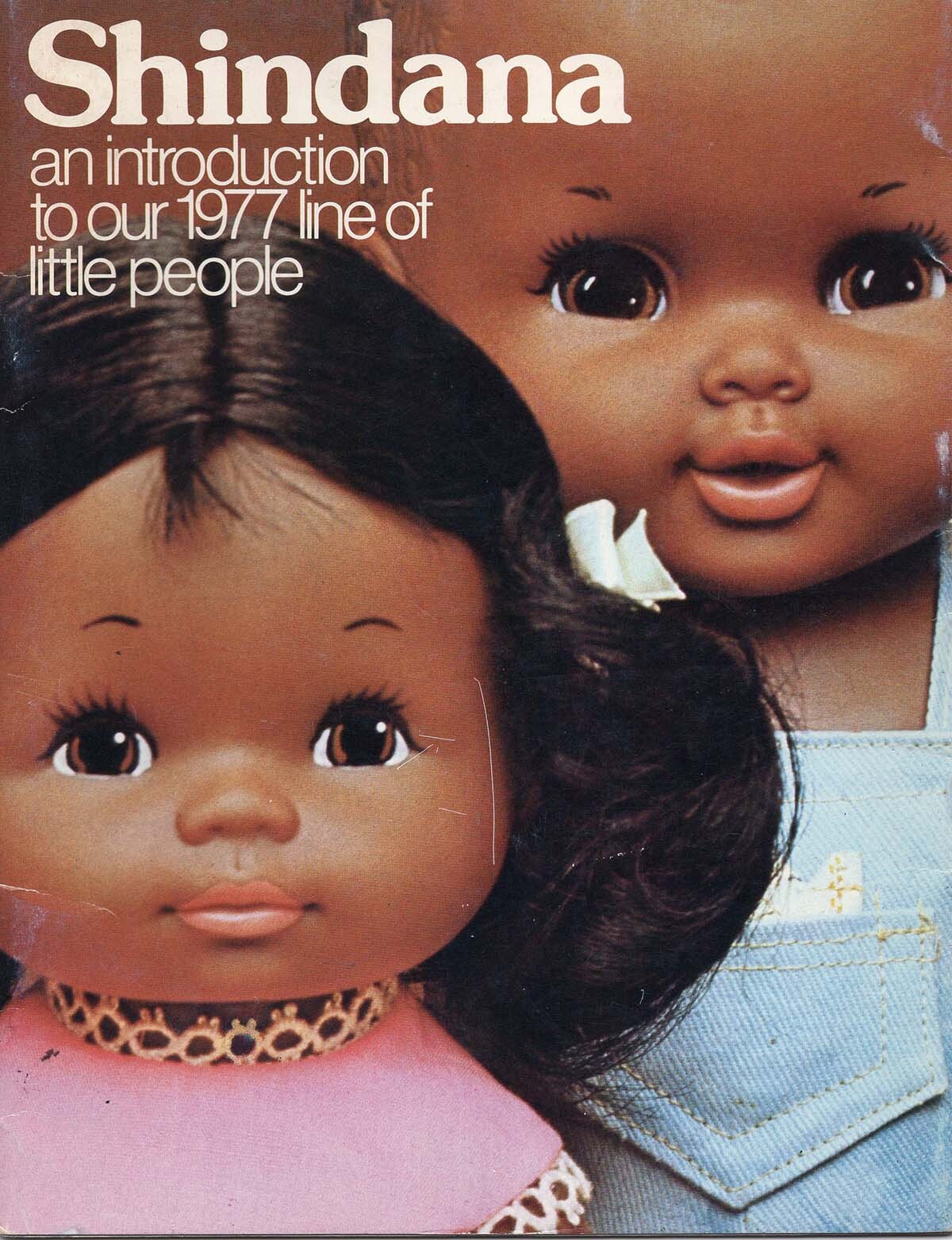

In 1968, just before the holiday season, the Shindana Toy Factory released its first doll, the Baby Nancy doll. This introduction to the market would be the start of something game-changing for the toy industry, the Black doll market and have tremendous impact on a tight-knit community in South Los Angles. In the succeeding years, the Shindana Toy Factory would go on to become the largest manufacturer of Black dolls and toys. It would be credited as the first company to mass-produce "ethnically correct" black dolls.

The company's unequivocal success exposed a long-standing demand for "ethnically correct" black dolls — dolls that authentically reflect the features, hair and skin color of black people — that had gone unheeded by the mainstream market. It wasn't the first to attempt the introduction of authentic black dolls, but it was by far the most successful. Shindana Toy Factory, a Black-owned company located in South Los Angeles, rose out of the Black community and experience. It was a community-driven effort that was an extension of Operation Bootstrap, a nonprofit founded by two activists in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion, Louis Smith and Robert Hall.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, many mass-produced black dolls were stereotypical, caricature-like and expressed racist undertones. Popular dolls included mammy, pickaninny and servant dolls. Some were made with exagger ated facial features and skin tone, while others were produced to act as servants to White dolls in children's imaginative play. For example, one popular doll was the Aunt Jemima rag doll, which was crafted as a marketing ploy to sell the pancake mix in the early 20th century. These dolls, often, did not garner the affections of black children and their families. Of the few companies that did attempt to produce non-offensive black dolls, many were white dolls that were painted black or brown. On the surface, these dolls were black, but their features were Eurocentric. For companies that decided to include one or two black dolls to their line of dolls, choosing the right shade of brown complicated production as companies risked defining blackness in such narrow confines that would displease black customers. White consumers made up a significant portion of the black doll market and had their own idea of what constituted a Black doll. A few manufacturers too considered the representation of blackness. Black dolls made up a small portion of the doll market, and manufacturers did not want to alienate White customers who made up the larger portion of the market. This left little choice for Black families who wanted to purchase a doll that reflected the positive qualities of the black experience and authentically represent black children. However, some individuals were making inroads.

In 1908, Richard Henry Boyd, a Baptist minister and businessman, founded the National Negro Doll Company after difficulty finding suitable black dolls for his children. Boyd was well versed in the ideology of "racial uplift" that had captured the political minds of the black middle class at that time and felt that Black dolls that were made with care and thoughtfulness could instill racial pride in black children. He understood the value of dolls as tools of socialization and utilized them to counter anti-black imagery for all children. An early advertisement for the dolls stated, "These toys are not made of that disgraced and humiliating type that we have been accustomed to seeing black dolls made of. They represent the intelligent and refined Negro of today, rather that the type of toy that is usually given to the children, and as a rule, used as a scarecrow." Originally, he convinced European doll makers to make quality black dolls which he would distribute. He provided them with photos of black children to model the dolls after. He debuted his first dolls in 1908, selling up to 3,000 in the first holiday season. He later opened his own manufacturing in Tennessee, but the company closed in 1915 due to financial issues.

In 1948, Sara Lee Creech, a white woman from Belle Glades, Florida, too, felt that the self-esteem of black children was built through their playthings. After watching two black girls play with a white doll, Creech went on a mission to produce a quality “anthropologically correct” black doll to aid the social-emotional development of black children. Creech, an activist in the Interracial and Women’s movements, felt that it was important for black children to have dolls that reflected their own heritage. She was well aware of the Mamie and Kenneth Clark’s “doll test” conducted in the 1940s that concluded that Black children had a preference for White dolls and the impact of that finding on their self-esteem. The results of the test would go on to aid the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Creech enlisted an interracial group of supporters to her cause, including Zora Neal Hurston, Ralph Bunche and Eleanor Roosevelt. The Sara Lee Negro Doll debuted in 1951 and was manufactured and sold through the Ideal Toy Company, but was racked with challenges. Creech faced problems with materials and the color of the dolls and issues with lackluster distribution and marketing. The Ideal Toy Company stopped producing the Sara Lee Negro Doll in 1953.

There were other modest attempts to produce quality, authentic black dolls. The most hearty undertakings included: Marcus Garvey’s doll factory, Berry and Ross, through his Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1919; Beatrice Wright, an African American entrepreneur and educator, opened the B. Wright Toy Company in the 1950s and Jackie Ormes, the first African American cartoonist, produced the Patti-Jo Doll based on one of her cartoon characters. Although the demand for Black dolls grew over time, each of the companies closed or phased out due to a variety of reasons, from technical production issues to distribution and financial reasons. None of these efforts matched the national impact of the Shindana Toy factory.

In 1965, in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion, activists Louis Smith and Robert Hall found Operation Bootstrap, a community based non-profit that offered employment training to address high unemployment in South Central Los Angeles. Through their non-profit, Smith and Hall established Shindana Toy Factory. They too wished to fortify the self-esteem of Black children, but their efforts employed a dual mission of also providing an economic opportunity for an ignored black community in South Central Los Angeles.

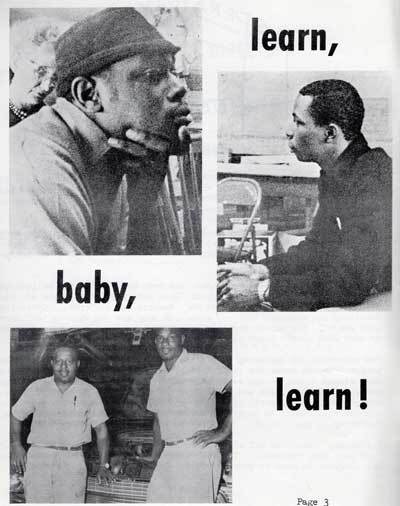

Louis Smith was an activist with The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). He was sent to Los Angeles as Director of the Western Region after his stint in Mississippi during Freedom Summer, following the murders of CORE activist Michael Schwerner, James Carney and Andrew Goodman. In Los Angeles, he met fellow activist and CORE member Robert Hall, who was active in the L.A. scene and had become chairman of The Non-Violent Action Committee (N-VAC), a group that formed after disenchanted members of CORE’s L.A. chapter splintered off. Smith’s charisma and national scope paired well with Hall’s in-depth understanding of local politics. The Rebellion only propelled and cemented their partnership and, in two months after the Rebellion and with a $1000 loan, Smith and Hall opened the storefront doors of Operation Bootstrap to offer job training to community members. They reframed the rioters chant of “Burn Baby Burn” with their own slogan of “Learn Baby Learn.” Shaped by community input, Bootstrap was also driven by Smith’s and Hall’s political leanings that converged the ideologies of Black Power and The Civil Rights Movements with ideas of community economic development and entrepreneurship.

In 1968, Smith and Hall opened the Shindana Toy Factory on 61st St. and Central Ave., a couple of miles south of their Bootstrap offices, to produce quality black dolls that promoted self-love in black children. Mattel helped financed and secure funds for their early vision. Arthur Spear, who became president of Mattel in the ‘70s, also made available staff and tools of the trade, giving Smith and Hall an insider's view of the production process. This would later prove invaluable as they worked to ensure the integrity and authenticity of their products.

Their first doll, Baby Nancy, entered the marketplace in 1968 in time for the holiday season. She was born in the midst of Black Power, Black Capitalism, the Civil Rights, the Black Arts Movements, and the many regional iterations of the black aesthetic that emerged in localized responses to national issues of civil rights, inequality and liberation. Shindana's product and business model could definitely be viewed as an assemblage of political influences, but its singular mission was to serve its community. Many of the staff, artists and personnel were African American and the company utilized this information in some of their advertising asserting their claim to authenticity. Baby Nancy was designed by African American sculptor Jim Toatley, who took great pains to ensure that the early face molds retained their Afrocentric features, even as parts of the production process were outsourced in the first year of business. This was key as some manufacturers, to reduce cost, would use the same production molds for both White and Black dolls. The first Baby Nancy had straight pigtails with curls, but Shindana quickly shifted to a soft afro style in keeping with the political trends of the times. This was groundbreaking as most Black dolls at that time were not crafted with "natural" hair.

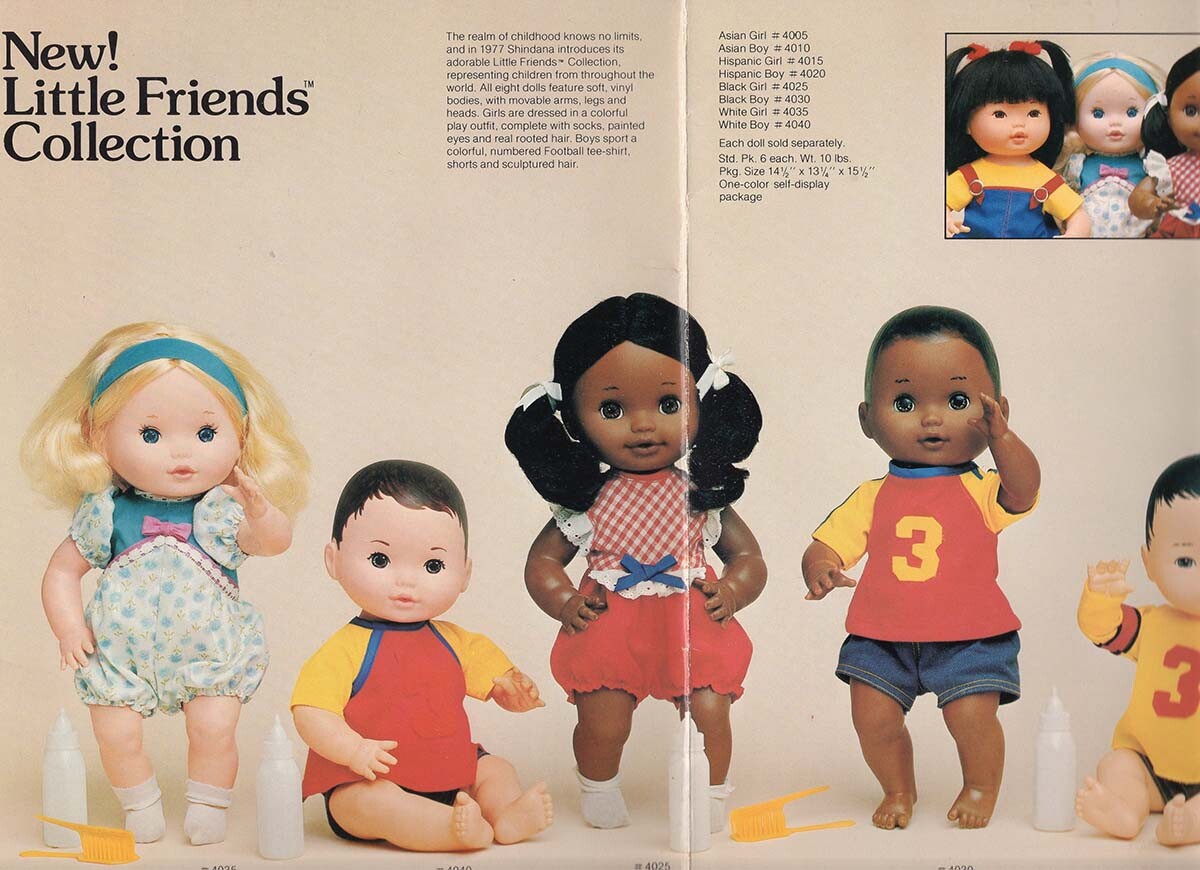

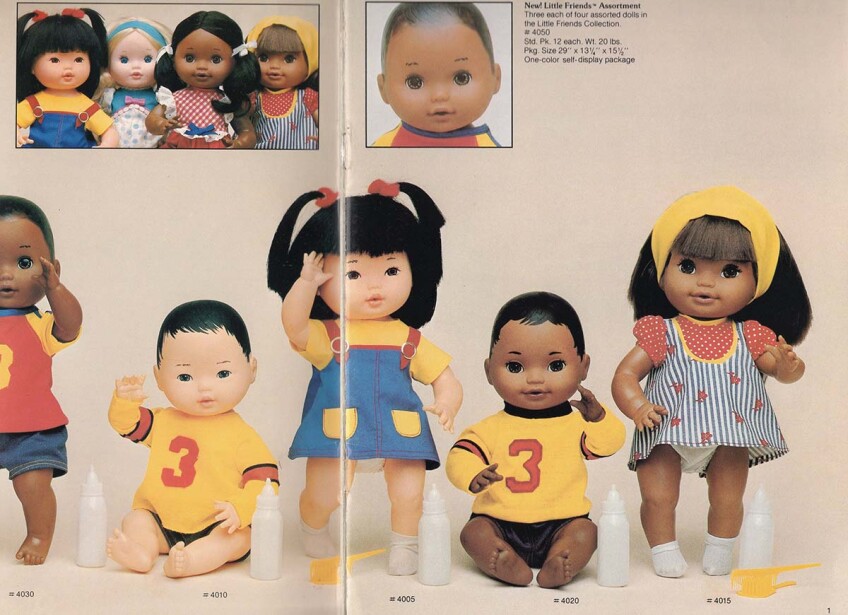

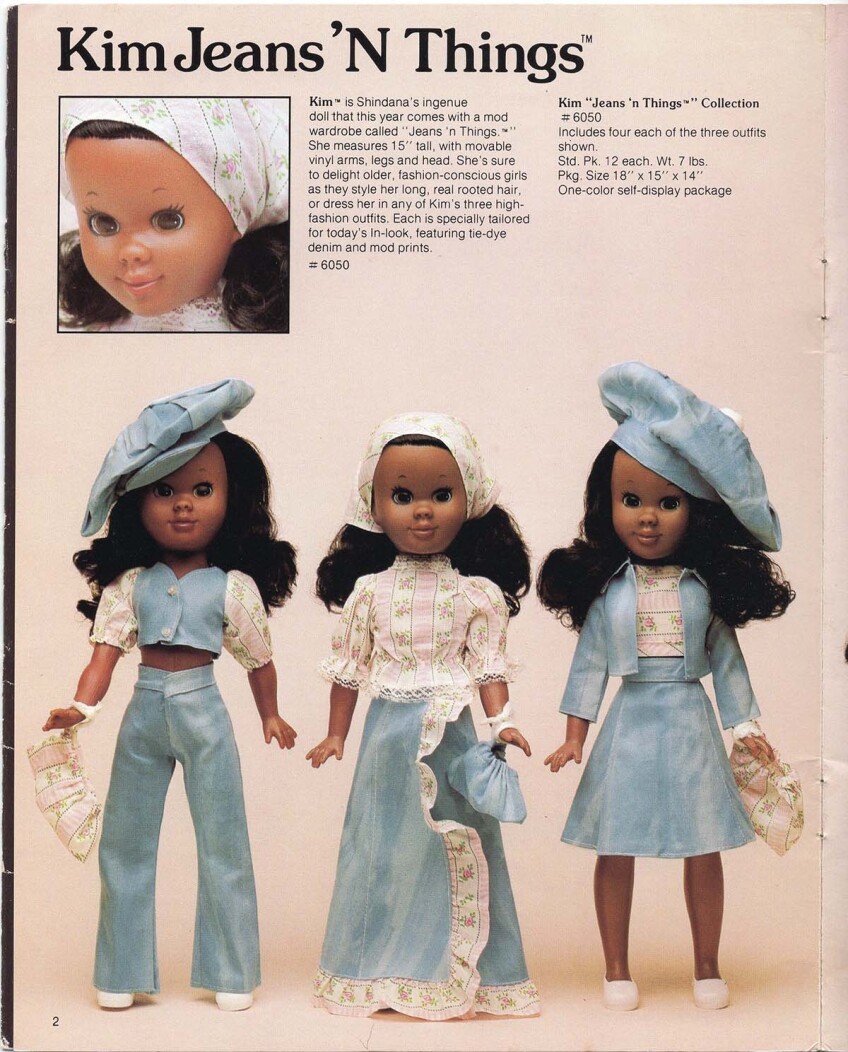

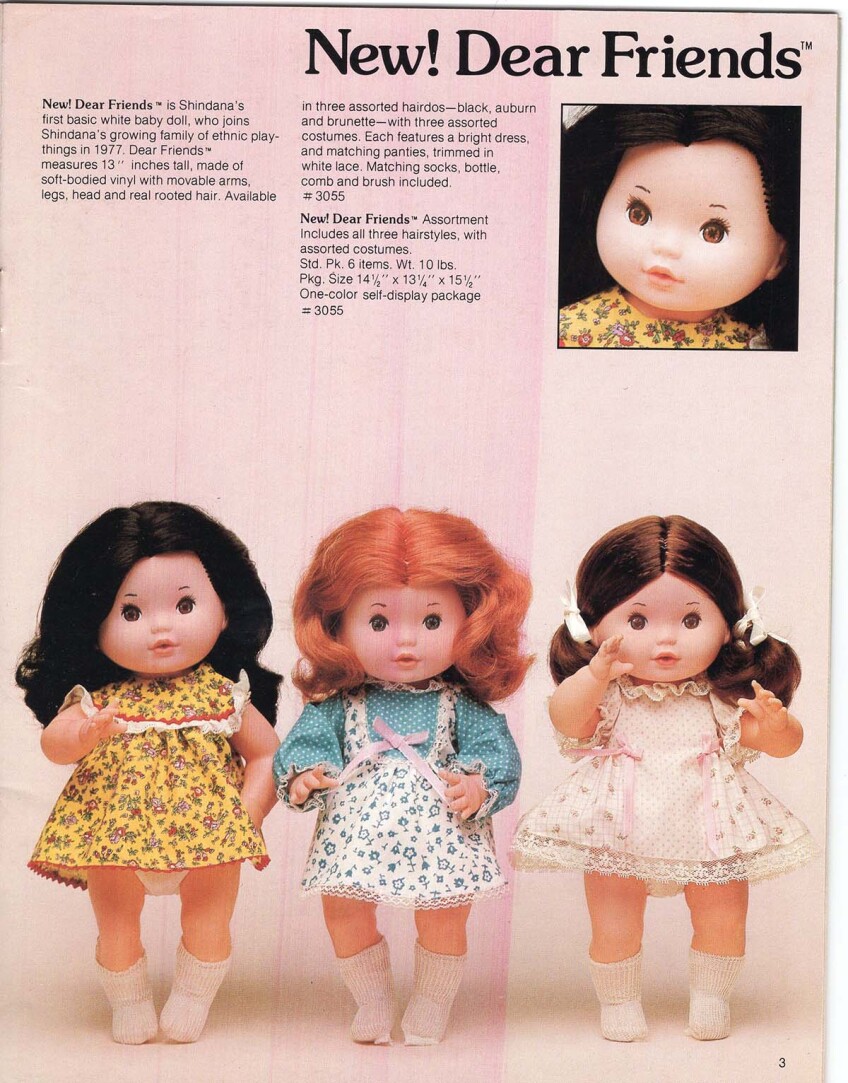

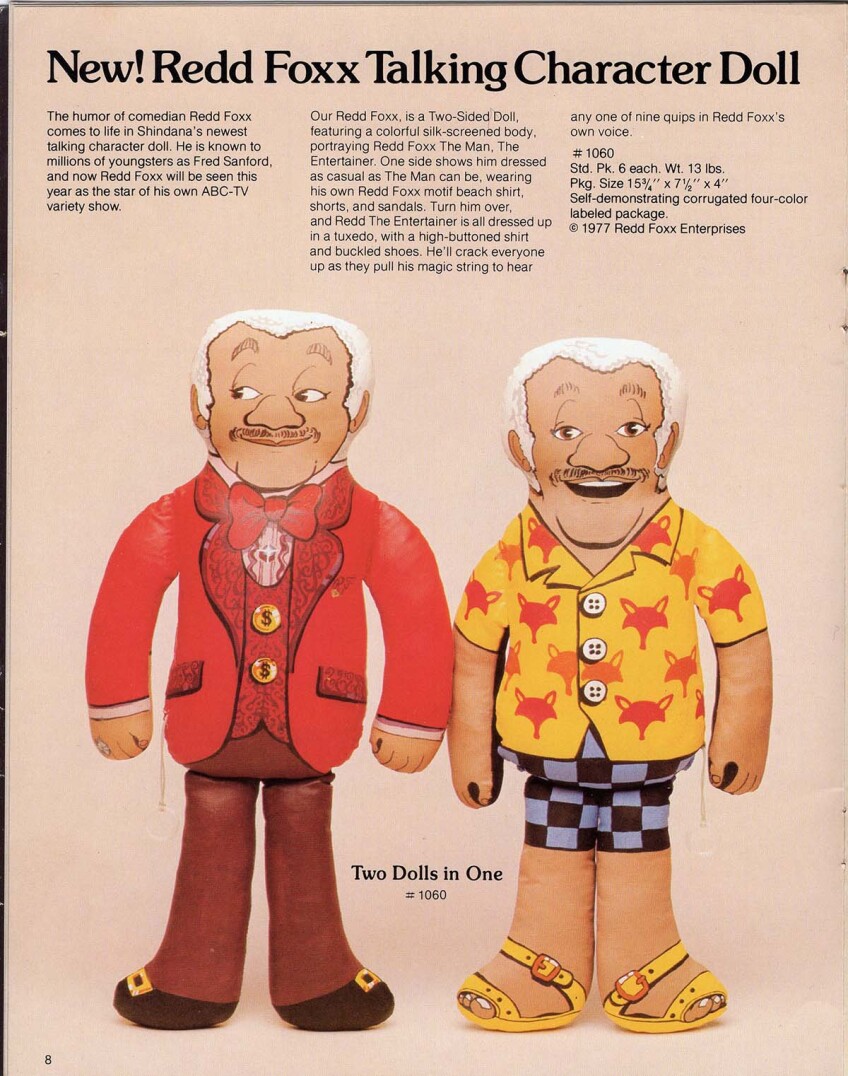

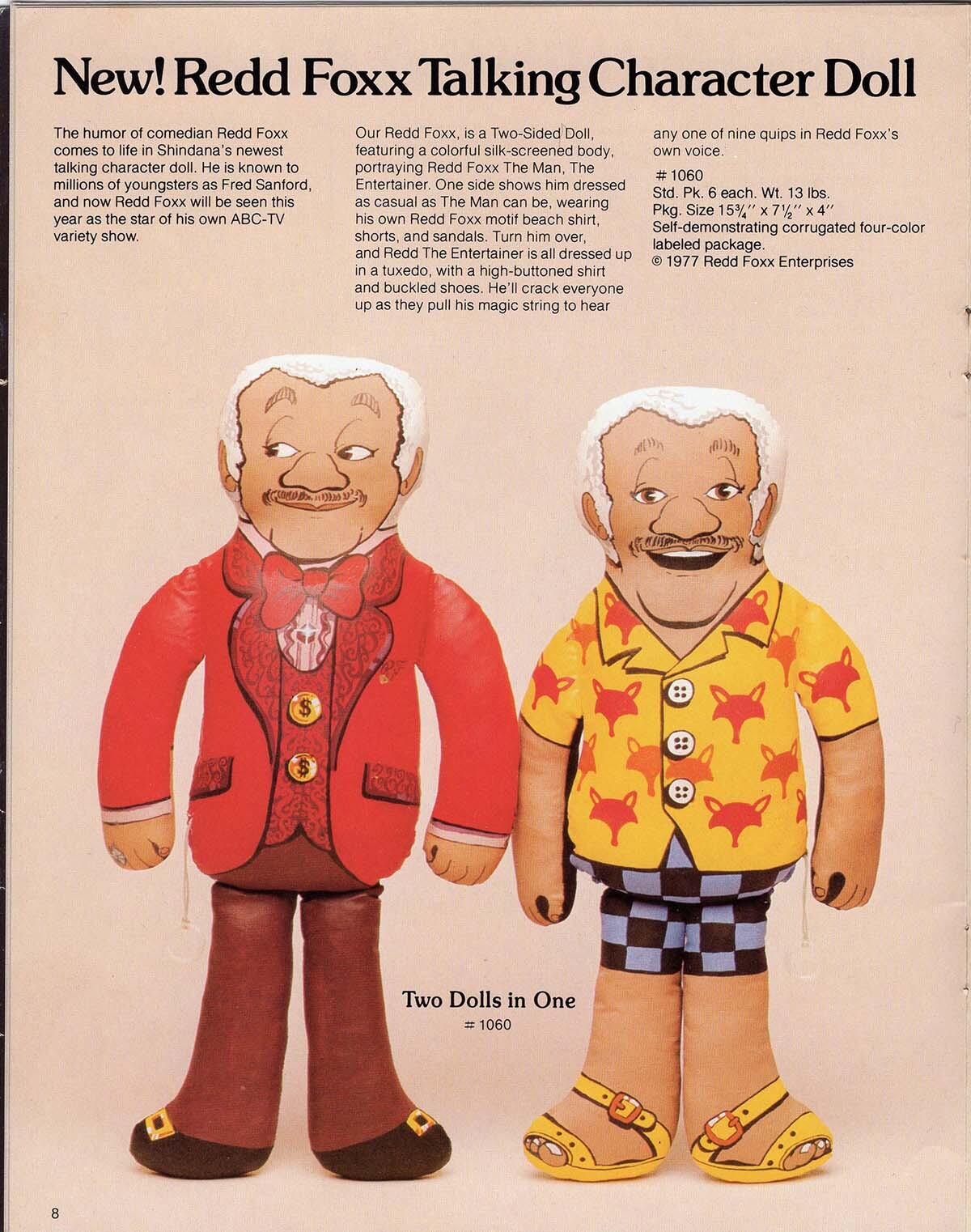

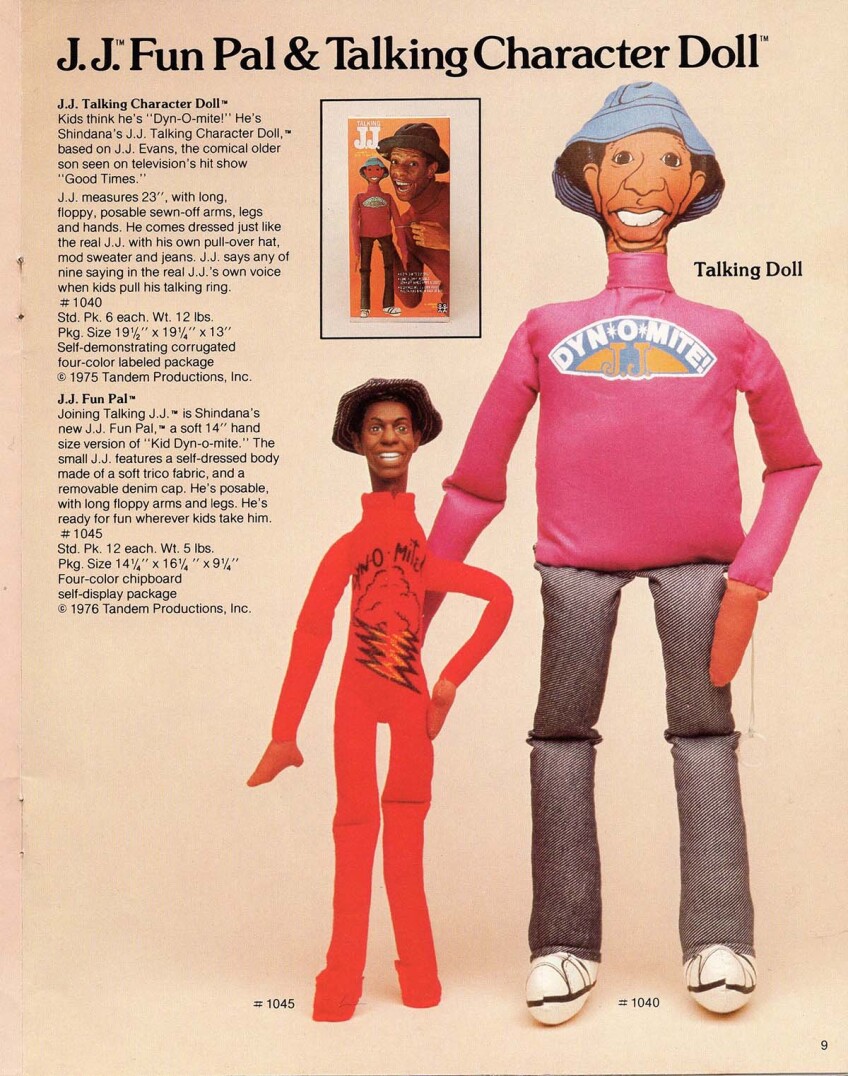

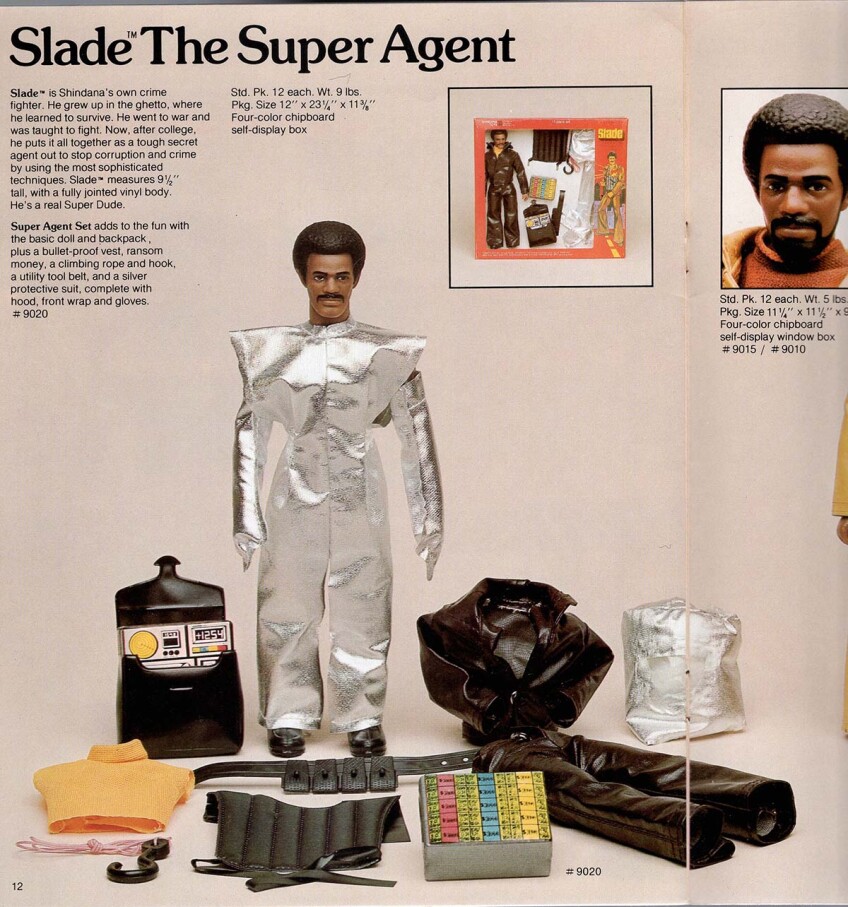

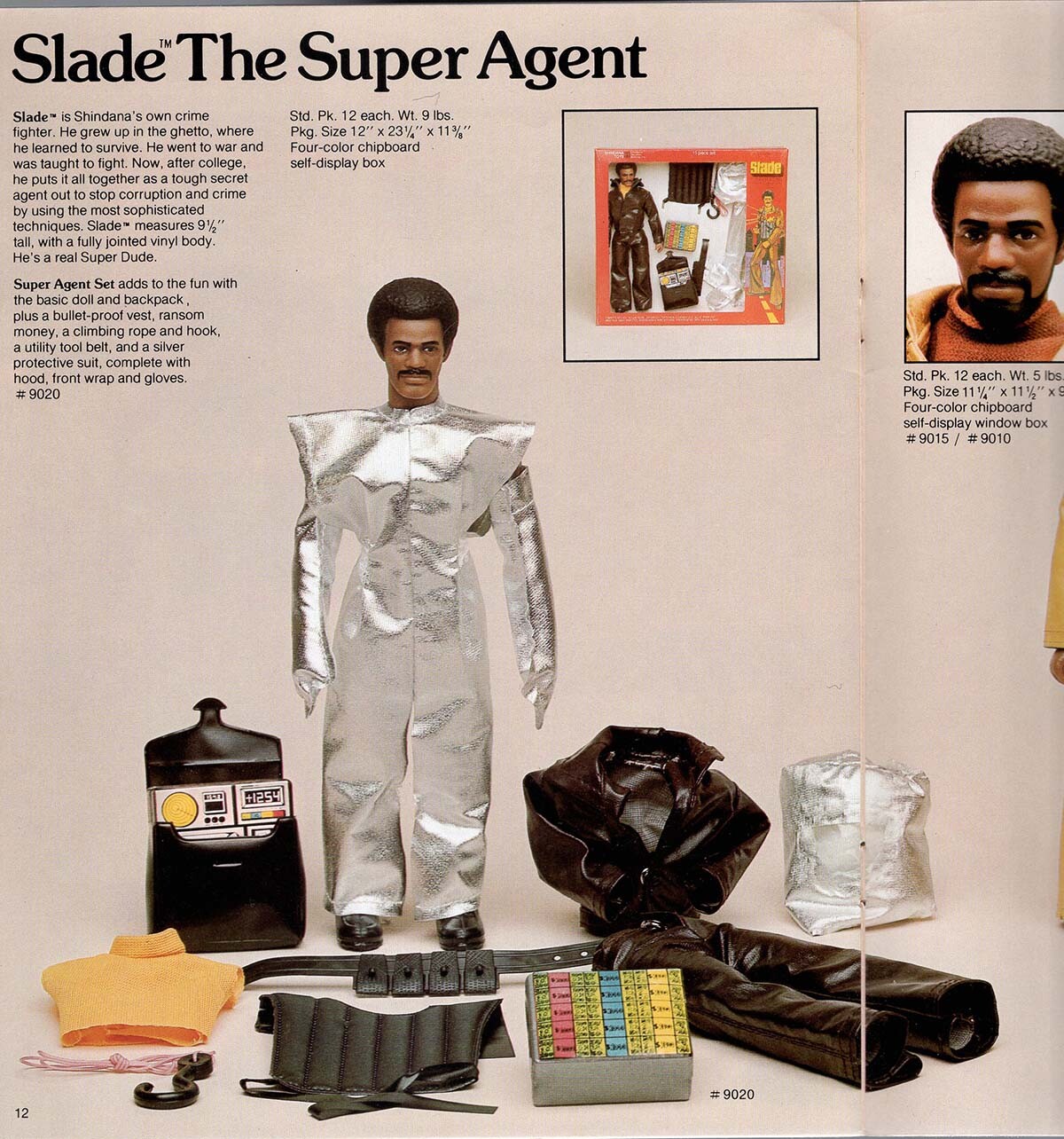

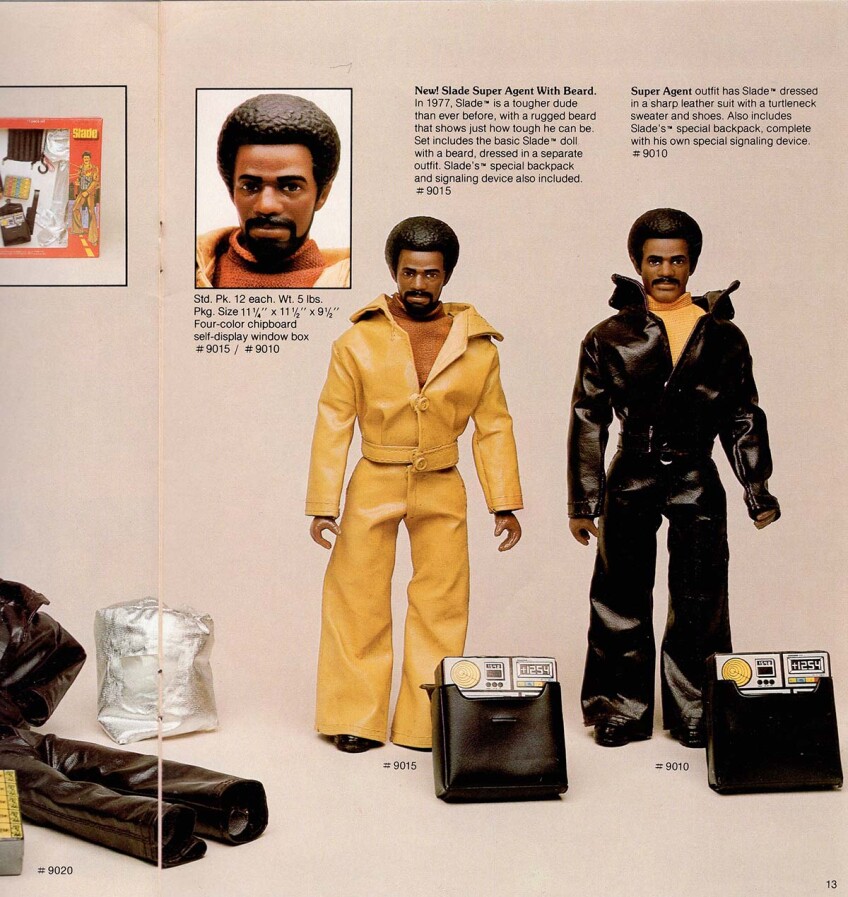

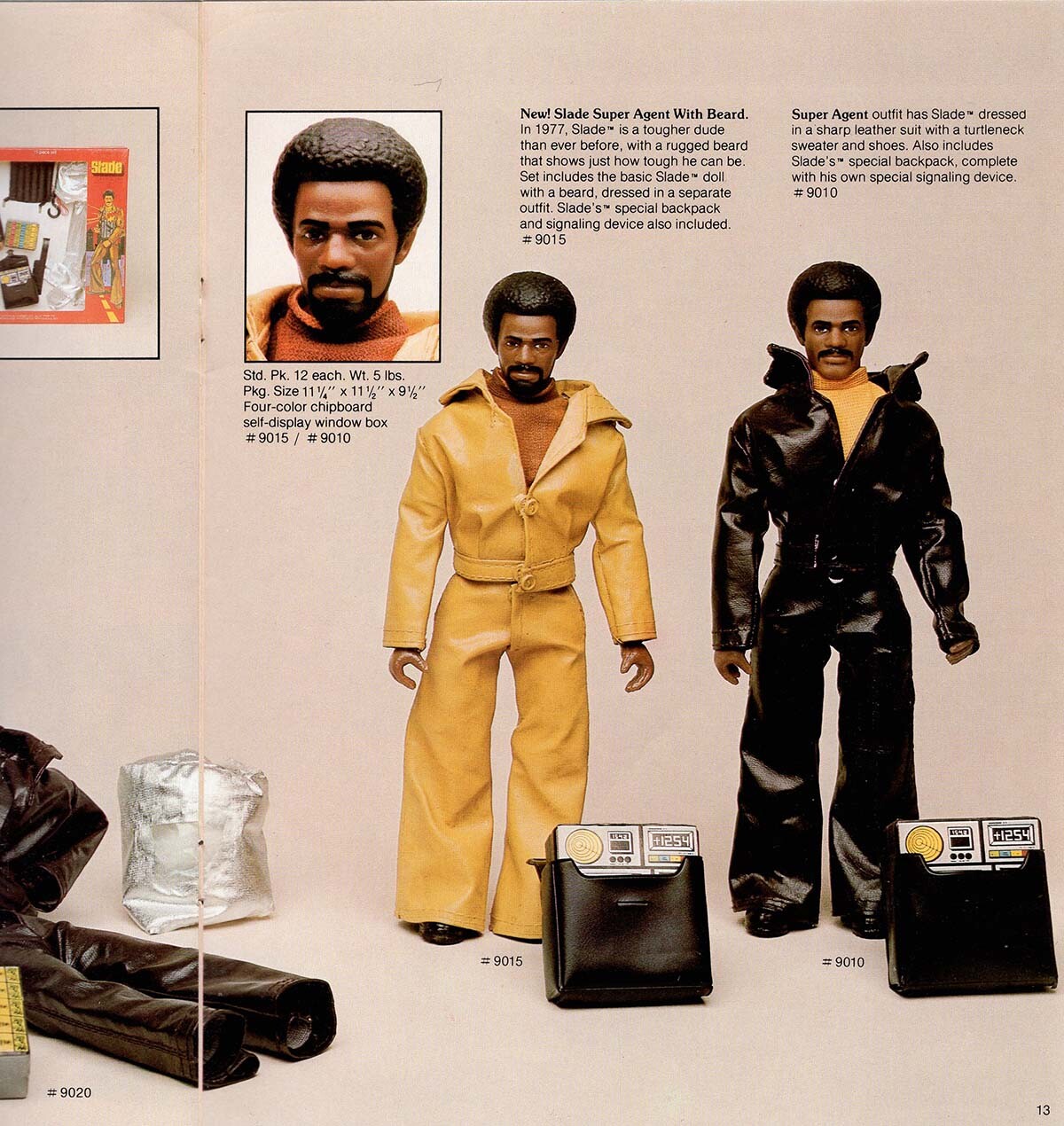

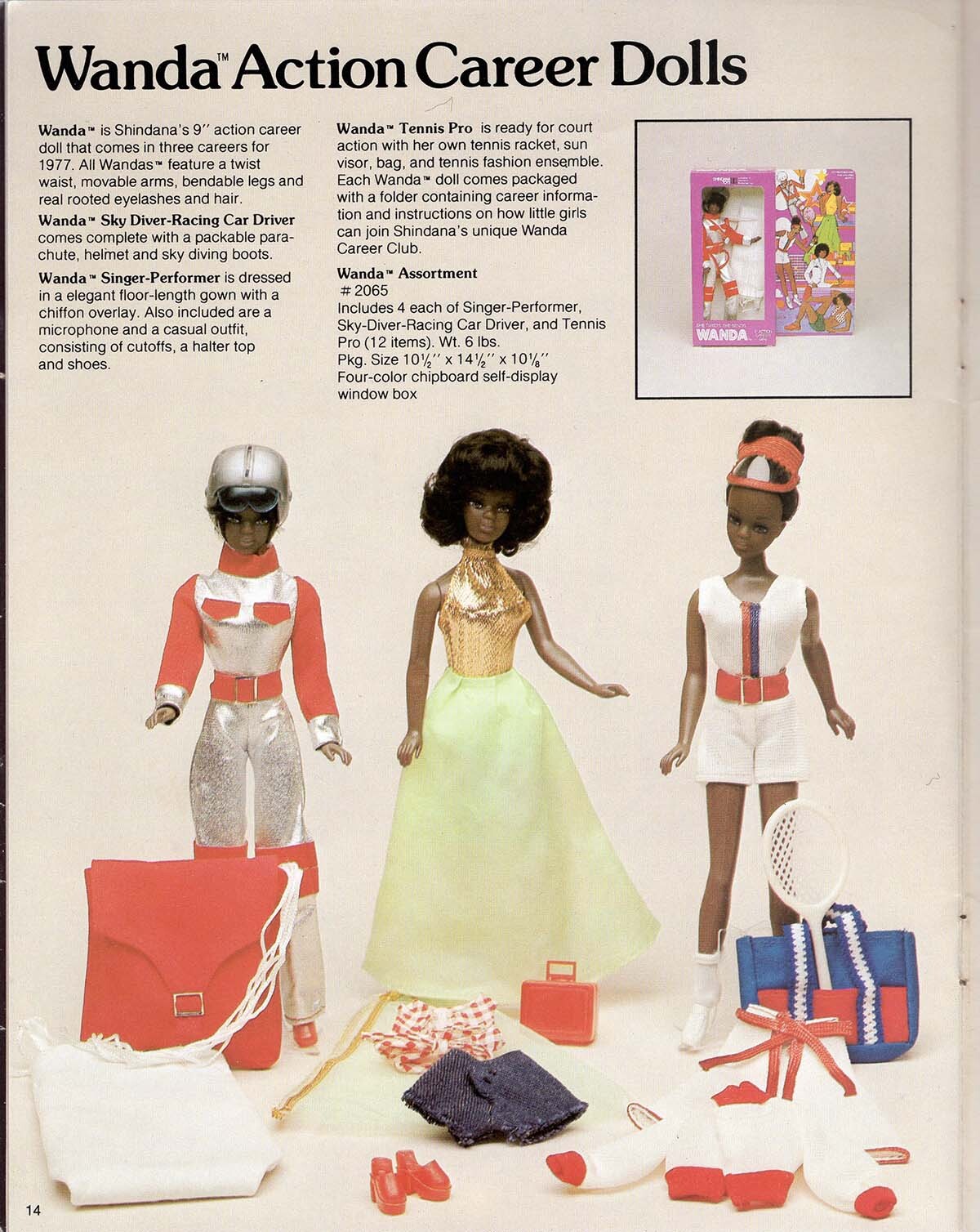

Over time, Shindana slowly added to their collection, with their Tamu doll, celebrity dolls, career dolls and action dolls for boys. By the mid-70s they had sales of $1.5 million, employed roughly 70 people and a product line that grew to 32 dolls and six games, becoming the largest producer of Black dolls and toys. One of their popular dolls was Talking Tamu, a pull-string talking baby doll that would say phrases such as “pick me up” or “lay me down.” They produced a line of cloth dolls called Cuddly Li’l Souls with natural hair and positive phases printed on their clothing such as "Right on," "Say it Loud" and "I'm Proud." Shindana expanded their market to include dolls for older girls such as their fashion doll, Career Wanda, who came with career-related accessories, they would later add Nurse Wanda, Stewardess Wanda, Ballerina Wanda and Singer Wanda dolls. Their Super Agent Slade was produced to include boys in their selection. They also took advantage of their proximity to Hollywood and the growing representation of African Americans in media with a line of popular celebrity dolls including Flip Wilson, Jimmie Walker, Redd Foxx, OJ Simpson and Michael Jackson dolls. Later, they would include Afrocentric board games and other toys. As Shindana grew, their distribution grew both nationally and globally. By the mid-70s, Shindana had open distribution agencies in New York, Chicago and Houston and were shipping dolls to Canada, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, all anchored by its central manufacturing in South Central Los Angeles. Its success highlighted the potential of an ignored ethnic doll market, and its process offered a blueprint to authenticity, impacting the toy industry in a lasting way.

Click right and left to see the different types of dolls Shindana Toys offered:

1983 Shindana ceased production. It lost its visionaries with the death of Robert Hall in 1973 and Louis Smith in 1976. It continued under the leadership of other Bootstrap members but faced rising competition from mainstream companies who, due to Shindana's success, turned their attention to the ethnic doll market. Today, the dolls are popular in the collectors' markets. What's often remembered of the Shindana Toy Factory are the dolls and the company's impact in shaping how the toy industry engages with the ethnic market, but equally significant was its impact on a community, shifting a narrative of "blighted" and disadvantaged to one of resource, productivity and beauty.

Sources

“Black Firm Joins the Toy Industry.” Ebony, Johnson Publishing Company, Inc, December 1969.

“Bootstrap Efforts Pay $250,000 in Profits.” Los Angeles Sentinel, December 23, 1971.

Goldberg, Rob. “Baby Nancy, the First ‘Black’ Doll, Woke the Toy Industry .” Los Angeles Times, March 12, 2019.

Goldstein, Nancy. Jackie Ormes: the First African American Woman Cartoonist. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Hunter, Charlayne. “Black Doll Is ‘Natural’ Success.” New York Times, February 20, 1971.

Johnston, David Cay. “Arthur Spear, Who Led Mattel Through Fiscal Crises, Dies at 75.” New York Times, January 4, 1996.

“Lou Smith Killed.” Los Angeles Sentinel, January 8, 1976.

“Maker of Black Dolls Finding Profits in Attitude Changes.” New York Times, December 24, 1976.

Onion, Rebecca. “Fifty Years Before Boondocks There Was Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger.” The Vault, August 13, 2013.

Patterson, Gordon. “Color Matters: The Creation of the Sara Lee Doll.” The Florida Historical Society Quarterly 73, no. 2 (October 1994): 147–65.

Perkins, Myla. Black Dolls: 1820-1991: an Identification and Value Guide. Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 1993.

“Robert Hall Dies; Final Rites Said.” Los Angeles Sentinel, September 30, 1973.

Thomas, Sabrina Lynette. “Sara Lee: The Rise and Fall of the Ultimate Negro Doll.” Transforming Anthropology 15, no. 1 (2007): 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1525/tran.2007.15.1.38.

“Toy Co. Gets Capital Boost.” Los Angeles Sentinel, August 19, 1976.

Willis, Deborah, and Carla Williams. Black Venus, 2010: They Called Her "Hottentot". Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2010.

Oral Histories:

Crittendon, David, oral history

Smith, Marva, oral history

Kisasi, Lewis, oral history

Top Image: A little African American girl holding a doll | California State University Northridge