Sammy Lee: A Life That Shaped the Currents of California and U.S. History

Lives are lived. They span decades; they inhabit moments, eras, and epochs. For all of us, our lives thread their way through the currents of the day, but few of us shape the tide of national history. Sammy Lee, however, surfed historical crests and, as news of his death reached the public this past weekend, his life received the proper attention it deserved in the pages of the Los Angeles Times and New York Times.

Much has been made of his contributions to ending segregation in California and fighting communism abroad, his accomplishments as a gold medalist diver, and his success as a doctor. Indeed, even in his last days as he struggled with dementia, Lee remained a conduit for our national story over the century.

Lee began his life as America turned inward.

Born Aug. 1, 1920, in Fresno, California, the son of Korean immigrants, Lee began his life as America turned inward. World War I had proven a disappointment, the “War to End All Wars”, ended with a frustrating show of caprice by European powers. The U.S. Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and in the years that followed, Congress passed new immigration laws that sharply limited immigration from Southeastern and Eastern Europe and doubled down on restrictions placed on Asia, completely banning newcomers from the region. This is to say nothing of the alien land laws that California and other western states had passed earlier in the century, which prevented many Asians from owning property. That Lee died in a similar moment of retrenchment should not be ignored.

Lee came of age in a segregated California. Admittedly, white Californians did not exert segregation as severely as their Midwestern or Southern counterparts, but segregation undoubtedly shaped his life and the lives of others like him. By the late 1920s, he and his family had moved to the Highland Park district of Los Angeles. He practiced his diving skills at Brookside Pool in nearby Pasadena, but could only do so on Wednesdays, so called International Day – a perverse framing of segregation as cosmopolitanism and the only time Latino, Black and Asian Californians could use the facilities. As it so happened, Brookside cleaned its pool every Wednesday after its non-white patrons had finished swimming, a common practice across the U.S. as fears of interracial sexuality and racist ideas about hygiene reinforced segregation’s tenets. White families picketed the Lees' presence in Highland Park; Lee also heard the occasional racial slur in his neighborhood and at school.

No matter – Lee saw himself as an American and one deserving of the same rights as any other citizen. When a vice principal at Franklin High School advised him to take his name off the ballot for student government president, Lee barely blinked, telling him: "My fellow classmates do not look at me as Korean. They look at me as a fellow American." His father, an immigrant to America, encouraged Lee to not retreat from his nation or his ethnicity. "Son, you were born a free American,” the elder Lee told his son. “You can do anything you want because you're free, but if you are not proud of the color of your skin and the shape of your eyes, you'll never be accepted."

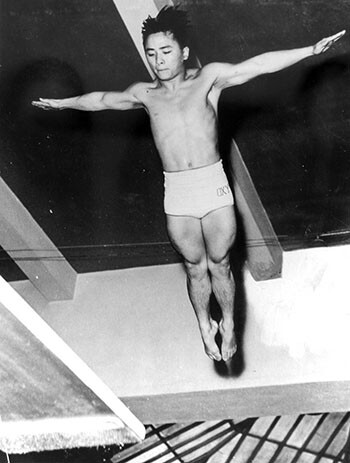

Lee became Los Angeles city diving champion in 1939, won three national collegiate diving championships while attending Occidental College, and then followed these achievements with Olympic gold medals in 1948 and 1952. At the 1948 Olympics, Lee was among the first two Asian-Americans to earn gold (along with Victoria Manalo Draves, who did the same two days prior) and the first American to win consecutive gold medals in platform diving. Attending medical school at the University of Southern California, he completed his work in three years on the military’s dime as a member of the Army Reserve. Lee later trained Olympic medalists Greg Louganis and Bob Webster; both legends in the sport. Louganis, a four time gold medalist remains arguably the best-known American diver ever, and Webster, under Lee’s tutelage, became the second American to win back-to-back gold medals in platform diving. Intentionally or unintentionally, Louganis also emerged as a pioneering role model for LGBT youth.

From 1946 to 1955, Lee served in the military, including a tour of duty in the Korean War, in which he was stationed just outside of Seoul as an Army major and medical officer. During these years and afterward, he helped spread the message of American democracy across Asia for the State Department even as Asian-Americans could find no purchase in the suburbs of California, an issue that Lee would soon encounter himself.

In many ways, California epitomized the nation’s Cold War mindset. World War II and the military-industrial complex it spawned built the modern Golden State, especially in the Southern California region. Military conflicts in East Asia from World War II through Vietnam resulted in larger flows of Asian immigrants to the state, forcing adaptations to immigration law. Lee’s own time in the military underscores this dynamic, but so, too, would his return to civilian life.

In 1955, Lee’s attempt to buy a home and establish a medical practice in the suburban Orange County community of Garden Grove became a national news story. Like Latino and African American service members, his veteran status initially accorded him little privilege. Yet the wave of Cold War rhetoric would help carry his family to suburban life. Even conservative-leaning publications like the Orange County Register recognized the need to broadcast to the world, and especially East Asia, American racial beneficence. Ironically, though they were treated as “perpetual foreigners” throughout their time in the United States, this very “foreignness”, historians like Charlotte Brooks have argued, would help Asian-Americans secure a place in burgeoning suburbia.

"The story of Major Lee's reception in Garden Grove will embarrass our country in the eyes of the world," the San Francisco Chronicle opined.

Initially, Garden Grove real estate agents refused to sell Lee a home and openly confessed that to do so would cost them their livelihoods, reflecting the depth of segregation at the time. "Here was an American of Oriental descent, demonstrating to Asians that despite Communist propaganda the United States is a land of tolerance and opportunity," the San Francisco Chronicle pointed out. "The story of Major Lee's reception in Garden Grove will embarrass our country in the eyes of the world." Due to the controversy, Lee and his wife, Rosalind, eventually purchased a home in Garden Grove. Undoubtedly, it was a civil rights victory, but one that revealed the unevenness of equality in America. Regrettably, Latino and African Americans would struggle to do the same, thereby demonstrating the all too obvious limits of America’s racial inclusion. The Model Minority myth, one that Lee seemed to embody as an Olympic athlete and doctor, along with the need to win over allies in Asia amidst the Cold War, overcame embedded racial prejudices, at least to a point. Notably, scholars like Ellen Wu and Erika Lee have recently argued that Model Minority tropes obscure a great deal while distorting Asian-American identity and United States history.

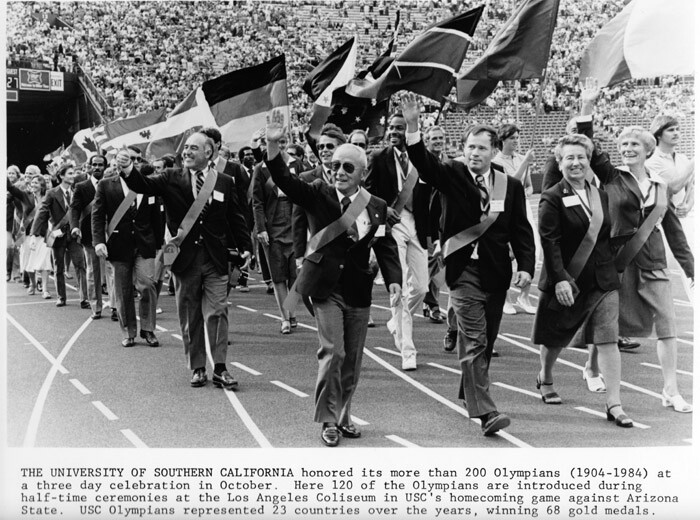

When USC established its Korean Heritage Library in 1986, Lee joined a Friends of the Library group as co-chairman, lending his prestige to fundraising efforts.

To this end, later in life, Lee made further contributions to Asian-American history. When USC established its Korean Heritage Library (now part of the USC Libraries) in 1986, Lee joined architect David Hyun as honorary chairmen of a Friends of the Library group that consisted of 25 members drawn nearly exclusively from the post-1965 wave of Korean immigration. Lee and Hyun represented the “success stories of the Korean Pioneer (pre-1965) second generation” Kenneth Klein, head of USC’s East Asian Library, noted in an email. Many members of the group took advantage of their international connections to donors in Korea while also leveraging relationships within the “business and professional circles” of Korean-Americans in the US.

Explore some of the spaces in Orange County shaped by conservatism and activism. Click on the starred map points to read more in-depth stories.

Lee lent his prestige to the Friends’ fundraising efforts. The resulting endowment has allowed the Korean Heritage Library to document the contributions of Korean-Americans to California and U.S. history while highlighting the community’s commitment to an independent Korea. In addition to his promotional support, Lee donated two scrapbooks from the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, along with the original manuscript from his 1987 biography “Not Without Honor: The Story of Sammy Lee,” which offers much greater detail about Lee’s life than the published account.

Over the course of his final years, Lee struggled with dementia. In 2013, he disappeared for several days before turning up in Pico Rivera, unscathed. Like millions of other Americans struggling with the affliction, he again inhabited the nation’s collective consciousness. Unfortunately, his story seems also to be representative of a larger national memory loss.

The California Lee leaves behind appears far from the racist Cold War Golden State of the mid-20th century.

The California Lee leaves behind appears far from the racist Cold War Golden State of the mid-20th century. Amidst amnesiac slogans like “Make America Great Again,” California undoubtedly expresses a more forward-looking outlook. Its majority-minority electorate, its embrace of environmentalism, its protection of immigrant rights, its renewable energy industries, and a slew of other policies mark the state as a true outlier in current political debates.

Even the state’s most conservative institutions have changed. Seventy-five years ago on the eve of Pearl Harbor, the military could arguably have been described as one of the most segregated institutions in American life. During World War II, the state famously interned its Japanese-American residents. Much has changed.

Since the armed forces’ desegregation in 1948 – a process Lee witnessed and no doubt experienced himself – the military now serves as one of the most integrated institutions in the nation. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor cited the military’s racial policies in her opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, the groundbreaking 2003 U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld the affirmative action policies at the University of Michigan. As of 2014, nearly one-third of active duty enlisted personnel are racial and ethnic minorities, and nearly one-quarter of its officer corps. The military and war occupies a central role in both Lee’s and California’s collective history.

Lee’s life, from start to finish, proves that hope for a better, more inclusive nation exists.

One could argue hashtag slogans like #MAGA ignore the complex and disappointing history of the nation’s racial, ethnic, and gender relations, while also framing its present course as an impending disaster. For many observers, Lee’s life bears witness to the blind spots of such slogans. If something required swaths of the American populace to be under the heel of discrimination, how truly great was it? While it might have been great for some, surely it was not great for all; sometimes, as with Jim Crow and segregation, America deliberately withheld this greatness from entire populations. Rather, his battles demonstrate that the nation’s genius is not inherent, but must be cultivated and nurtured. The “shining city on the hill,” as Ronald Reagan preferred to describe it, derived its sheen from the struggle for a more equitable future, not backward-looking nostalgia. Lee’s life, from start to finish, proves that hope for a better, more inclusive nation exists.