Red Flags Over Los Angeles, Part 2: Bombs, Betrayal, and the Election of 1911

Labor organizer and Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926) is a hero to Sen. Bernie Sanders. To a broad range of policies – workers’ rights, regulation of corporations, finance, taxation, and benefits for the poor – both Debs and Sanders apply socialist principles. But their socialisms are very different.

That they’re not the same begins with the events of 1910.

Bombs, betrayal, and Job Harriman’s failed campaign for mayor of Los Angeles helped determine what American socialism became in the 20th century.

Part 2: “The election of Harriman would result in an orgy of evil.”

Job Harriman’s gifts for organizing and oratory had helped the Los Angeles branch of the Socialist Party grow from just seven affiliated clubs in 1890 to a countywide network with members in Santa Monica, San Pedro, Glendale, Long Beach, Bellflower, Buena Park, Fullerton, and other communities. He had barnstormed the state while running for governor on the socialist ticket in 1898. In 1900, as the party’s vice presidential candidate, Harriman ran with Debs on the Socialist Party ticket.

Harriman was even better known in Los Angeles as the defender of union members jailed for violating the city’s anti-organizing and street meeting ordinances.

Harriman’s true opponents, however, weren’t at city hall. They were at the Los Angeles Times building on First Street, personified by Harrison Gray Otis, the paper’s fiery antiunion publisher, and in the boardroom of the Merchant and Manufacturers’ Association, whose members were just as reactionary as Otis. According to the San Francisco Bulletin, the members of the Merchant and Manufacturers’ had only one principle: “We will employ no union man.”

In addition to being an advocate of progressive causes, Harriman was on the right side of the ideological split within the socialist movement which separated the moderate majority that followed Eugene Debs from a faction led by Daniel De Leon, one of the founders of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

For Harriman, capitalism would be reformed by union solidarity, Socialist Party leadership, and the ballot box, not by bombs and bullets. 1910 tested each of these propositions.

It was a year of labor militancy. Garment workers were on strike in Chicago and New York. Transit workers led a citywide general strike in Boston and Philadelphia. Miners picketed in Colorado and Texas and steel workers in Pennsylvania. In Los Angeles, members of the press union local were still on strike against the Times. By the end of 1910, with the support of the member unions of the city’s Central Labor Council, butchers, trolley car drivers, painters, brewers, and workers in other trades would join them.

And it was a year of labor violence. Police used billy clubs to break up picket lines in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Strikebreakers used their fists. Union members fought back, sometimes with greater violence. Since 1906, the Iron Workers union had conducted a campaign of dynamiting non-union plants. By the -end of 1910, bombs set at 110 iron works around the nation had caused several thousand dollars’ worth of damage but as yet no injuries or deaths.

In June 1910, workers in the metal trades in Los Angeles, including members of the Iron Workers union, went on strike for a minimum wage guarantee and an eight-hour day. The Merchant and Manufacturers’ Association raised $350,000 from its members to break the strike with scab replacements. The scabs repeatedly clashed with union picketers through the summer and into the fall.

The city council, goaded by Otis and the Times, unanimously passed an anti-picketing ordinance (drafted by Merchants and Manufacturer’s Association lawyers) that additionally criminalized “speaking in public streets in a loud or unusual tone.” Union picketers refused to obey, and nearly 500 were arrested, crowding both the city jail and the courts. Harriman renewed his defense of jailed strikers, and few were convicted.

Union organizers made use of public sympathy for the strikers, forming 13 new locals by September and more than doubling union membership overall. The Los Angeles branch of the Socialist Party, with Harriman as its appealing image, nearly doubled its membership. Harriman – defender of free speech, crusading socialist, champion of progressive reforms like votes for women – was a natural candidate to be the next mayor of Los Angeles. The next municipal election would be at the end of 1911.

A socialist victory, mayoral candidate Job Harriman promised, would make private utilities public, reserve Owens Valley water for city customers (not real estate speculators), put the industrial property around the new harbor under city management, and make property taxes progressive.

Harriman and his slate of city council candidates (one of whom was African American) campaigned on a platform of reforms that were already popular among middle-class Angeleños. A socialist victory, Harriman promised, would make private utilities public, reserve Owens Valley water for city customers (not real estate speculators like Otis), put the industrial property around the new harbor under city management, and make property taxes progressive. To rally union member support, Harriman distributed 20,000 copies of a pro-union pamphlet written by the celebrated labor attorney Clarence Darrow.

Harriman’s opponent was incumbent Mayor George Alexander, a respected “good government” reformer who had won a recall election in 1909 that swept out the flamboyantly corrupt Arthur C. Harper, one of many political hacks that Otis and the Times supported. In the 1911 primary election, Harriman beat Alexander by nearly 4,000 votes in a three-way race but failed to reach an outright majority that would have prevented a runoff election on December 5.

A new class of voters would determine if Harriman and the socialists or the Good Government League would run city government. A California constitutional amendment had given women the vote in a special election in October, making California the fifth state to grant women suffrage. Both the socialists and Alexander’s backers hurried in November to register the estimated 60,000 women in Los Angeles who were now eligible to vote. Harriman confidently predicted that working women would vote their economic interests and give socialists control of city hall. The Good Government League hoped that middle-class women might hesitate to vote for Harriman and socialism. An article in Collier’s magazine pointed out that “women will decide who will be the next Mayor.”

“The election of Harriman,” Harrison Gray Otis fulminated on the Times’ editorial page, “would result in an orgy of evil, in a season of stagnation in businesses, in the curtailment of building, in the withdrawal of capital, in hunger in the homes and rioting in the highways.”

Fearing that the election might already be lost to the socialists, the Times reacted with its usual vehemence. “The election of Harriman,” Otis fulminated on the Times’ editorial page, “would result in an orgy of evil, in a season of stagnation in businesses, in the curtailment of building, in the withdrawal of capital, in hunger in the homes and rioting in the highways.”

But the choice wasn’t between revolution and reaction. Socialists under Harriman and good government reformers like Alexander advocated municipal ownership of utilities and public transit, the completion of the Owens Valley aqueduct and the Los Angeles Harbor, and social services for poor neighborhoods. What distinguished the two parties was socialist solidarity with labor union goals and tactics and the reformers’ distrust of them.

Otis and his son-in-law Harry Chandler, the paper’s general manager, had a personal, pecuniary reason to fear a Harriman victory. As partners in the land company that was poised to benefit from the new Los Angeles aqueduct, the two men knew that a socialist mayor and city council majority would wreck their plans for the thousands of dry acres they owned in the San Fernando Valley.

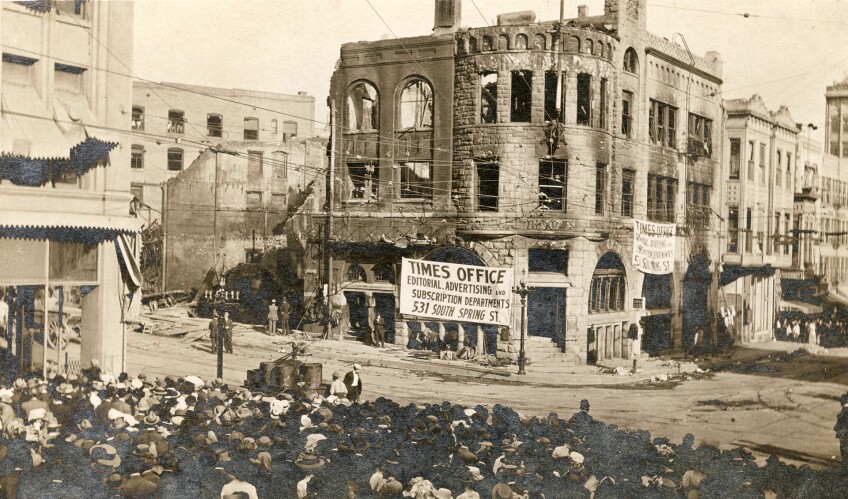

Even as the Harriman campaign gained momentum, the Iron Workers’ bombing campaign came to Los Angeles. About 1 a.m. on Saturday, October 1, while non-union typesetters and pressmen put out the Times' morning edition, a bundle of 16 sticks of 80 percent nitroglycerine, connected to a cheap alarm clock timer, exploded. The dynamite also ignited barrels of flammable printers’ ink. The fire quickly reached a damaged gas main. It consumed the interior of the building and collapsed its masonry walls. At least 20 Times employees died; 100 were more injured.

That morning, more time bombs were found at Otis’ home and the home of the Merchant and Manufacturers’ executive director. On December 25, while the hunt was on to find the Times bomber, another bundle of dynamite detonated at the Llewellyn Iron Works, partially wrecking the plant.

Otis and Chandler had anticipated an attack on the Times. They may have known the outline of the larger Iron Workers dynamite plot through an informant, paid by a building industry association, who was a member of the Iron Workers executive council. Even as the remains of the Times building smoldered, the Otis and Chandler activated a secret, second newsroom and printed a one-page edition whose headline screamed “Unionist Bombs Wreck the Times.”

It was the “crime of the century” that became the “trial of the century” in May 1911 when two Iron Workers organizers – brothers James and John McNamara – were indicted for murder and 20 other criminal charges. Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, immediately claimed that Otis and the Merchant and Manufacturers’ had railroaded the McNamaras under dubious circumstances. Debs hinted that Otis and Chandler had planted the bomb themselves to discredit union organizers, smear Harriman before the election, and vindicate the Times’ antiunion campaign.

Gompers, fearing a nationwide witch-hunt that would coerce unions to abandon organizing if the union men were found guilty, pledged $200,000 toward the McNamaras’ defense and another $50,000 to retain a reluctant Clarence Darrow as their attorney. Gompers directed union locals to donate 25 cents for each member and to set up McNamara defense committees to sustain popular support. Locals organized mass marches of members in 13 cities. Pins and other memorabilia were sold to raise even more money. “A Martyr to His Cause,” the first film produced by organized labor, premiered in Cincinnati, where an estimated 50,000 tickets were sold. Thousands more saw the film in other cities.

In Los Angeles, Debs made support for the McNamaras a test of socialist strength under the slogan “Fight Otis, organize the city, and elect a Socialist mayor – Job Harriman.” But Harriman’s defense of the McNamara brothers also colored the campaign, and supporters wore buttons that also read “McNamaras Innocent – Vote for Harriman.”

Harriman headed the McNamara defense team, but it was only for the publicity. Harriman’s focus was on his campaign for mayor and only occasionally on the trial, which Darrow, the rest of the defense team, and Gompers sought to delay until after Election Day in December.

The drawn out selection of jurors concealed what Darrow (and perhaps Harriman) already knew: that James McNamara, burdened by guilt, had earlier confessed his part in the bomb plot to Lincoln Steffens, a reform-minded magazine writer. But Darrow probably didn’t know that prosecutors had secretly listened as the McNamaras met with the defense team or that a paid informant in the Iron Workers union had given details of the dynamite plot to Otis and the city attorney.

It was now a race between Election Day and the date the trial would start. It was a trial Darrow knew he would lose, and there is evidence that he (or others on the McNamara defense team) sought to bribe one or more of the members of the juror pool to guarantee a hung jury and a mistrial. Darrow, desperate to save the McNamaras from hanging, also joined in back-channel negotiations with Harry Chandler of the Times that sought to trade the end of AFL-led strikes in Los Angeles for lenient sentences for the brothers and suspension of the Times’ “open shop” campaign. Chandler agreed to begin negotiations with district attorney John D. Fredericks on those terms.

Darrow also hoped that a plea bargain might salvage Harriman’s campaign, but Fredericks – who shared Otis’ fear of a socialist victory – refused. Nothing short of guilty pleas by both brothers in open court was acceptable if James, the older brother, would be spared a death sentence and John be given a relatively short prison term.

On December 1, before a jury had been seated and only four days before the election, the McNamara brothers changed their pleas in open court to guilty. James McNamara admitted to having set the bomb that destroyed the Times building on October 1, 1910. John McNamara admitted to having set the bomb that damaged the Llewellyn Iron Works on December 25.

Samuel Gompers of the AFL was crushed by the news of the confessions. “I am astounded, I am astounded,” he told a reporter. “The McNamaras have betrayed labor.” Debs and the Socialist Party refused to condemn the McNamaras, blaming Otis, the Times, and the Merchants and Manufacturers’ Association for creating a climate of labor terror. Darrow was indicted twice for attempted bribery of McNamara jury members. (At his trials in 1912, Darrow pleaded the case for labor justice that he had hoped to make for the McNamaras. Darrow was acquitted in one case and won a hung jury in the second.)

Support for Harriman and the union-socialist slate did not disappear in the days before the election, despite the shock of the McNamara confessions. Some of Harriman’s working-class supporters on the city’s eastside stayed away from the polls, but more westside voters, which included a large proportion of middle-class women, turned out for Alexander and his slate of bankers, lawyers, storekeepers, and real estate salesmen. When the ballots were counted, Harriman trailed Alexander by 34,000 votes, or 25% of the total ballots cast. Only one socialist candidate was able to win his city council seat.

Bombs and the betrayals of popular labor heroes in 1910 ended the possibility of establishing the kind of socialist party that might have made Bernie Sanders its candidate for president in 2016.

In some westside precincts, nearly all the newly registered women had voted. Their votes were credited by many observers for turning back the socialist tide. It wasn’t just the McNamaras’ confessions but ballots that caused the Harriman campaign to fail.

In the aftermath of the Times bombing and the trial, those who had defended the McNamaras were proved to be gullible (if not dishonest), conservatives and civic reformers were new allies, and the force of the labor movement in Los Angeles was ended. The Central Labor Council lost most of its member unions. Gompers and the AFL abandoned union organizing in Los Angeles. Employers redoubled efforts to maintain the “open shop” regime backed by the Times. And “good government” reformers would produce in the 1920s a technocratic city charter that still, even after significant revision in 1999, undercuts the democratic process in Los Angeles city government.

Unions in Los Angeles did not begin to show signs of new growth until the late 1950s.

By the end of the McNamara trial and after the election of 1911, socialism and the Socialist Party were suspect not only in Los Angeles but also nationally. What might have become a broad coalition of working-class union members and middle-class progressives failed to mature. Bombs and the betrayals of popular labor heroes in 1910 ended the possibility of establishing the kind of socialist party that might have made Bernie Sanders its candidate for president in 2016.

The USC Digital Library, particularly its collection of dissertations, provided research materials for this two-part series.