Ralph Hamlin: The Forgotten History of an L.A. Auto Pioneer

As the sun set, Ralph Hamlin’s Franklin roadster roared onto the track of the Phoenix fairgrounds. The date was Oct. 29, 1912 and at 18 hours, 20 minutes, and 22 seconds, Hamlin’s drive from Los Angeles to Arizona obliterated all previous records. Twelve cars had left LA’s paved city streets the day before. Far fewer completed the course. One car was wrecked when it swerved to avoid a spectator. Another driver took a curve too fast and rolled his Buick, pinning him and the car’s mechanic beneath the machine. A third car, unable to stop, hit the disabled Buick. Other vehicles could not maintain the punishing pace. Ten miles outside of the town of Brawley, the little Hupmobile rolled to a stop and refused to go further. At Glamis, in California’s Imperial Valley, the driver of the Schact walked away from his stalled car. The dunes of the Mammoth Wash, near the Arizona state line, were virtually impassable. Horses dragged most of the cars through.

After hours on the road, seven drivers pulled into Yuma to rest before attempting the final leg of the journey to Phoenix. Along the route, the desert sands had reddened their faces and cracked lips. The driver’s eyes were bloodshot, having “been almost burned out” of their heads. Dirt filled their mouths and noses. The dust was everywhere. The men showered and briefly slept. The following morning at 5:00 a.m., Hamlin and the remaining competitors “shot out” of town at 70 mph. They maintained this pace through Agua Caliente and Buckeye. The competition tightened as Hamlin and Charley Soules in a Cadillac traded spots for the lead. Twenty miles from Phoenix, Hamlin unleashed the Franklin and thundered towards the finish line, coming in 43 minutes ahead of his rival. It was a “nerve-wrecking, muscle-straining race.”[i]

A crowd had gathered at the fairgrounds to celebrate the end of the “Cactus Derby”. Ralph Hamlin was lifted onto sturdy shoulders and, with the “howdy band playing the worst music that ever was heard,” was carried to an immense grand stand. One of the other drivers grabbed a big bass drum and led the parade. Tears cleaned a path through the grime on Hamlin’s face. “When he brushed the tears away and mopped his red eyes…he showed himself a man who could appreciate the right kind of welcome.”[ii]

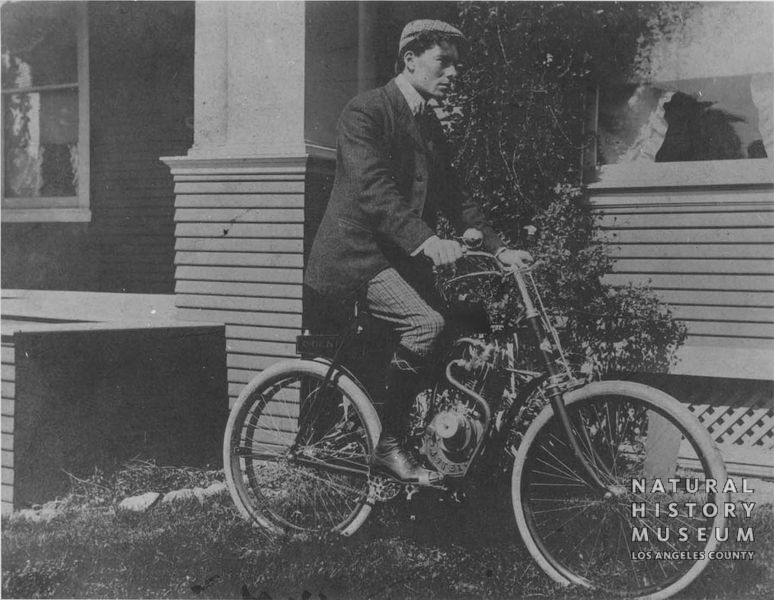

The Los Angeles to Phoenix race was Hamlin’s fifth and final attempt. He had been racing for close to 20 years, beginning with bicycles, then motorcycles and finally automobiles. Born in San Francisco in 1880, Hamlin moved with his family to Los Angeles in 1887. He began racing bikes at 16 and, after a few wins, saved enough prize money to establish a bicycle repair shop. In 1901, he leased a small space at 1806 S. Main St. and began selling motorcycles, Orient Buckboards, Lozier, and Scripps-Booth automobiles.

Four years later, Hamlin became the Southern California distributor for Franklin air-cooled cars, designed by the H.H. Franklin Manufacturing Company of Syracuse, New York. His original Franklin showroom was located at 1040 S. Flower St. He would go on to establish outlets in Hollywood, Pasadena, Glendale, and San Diego.[iii] Through a combination of “imaginative” public relations and shrewd business dealings, Hamlin became Franklin’s largest and most successful dealer, selling anywhere between 500 and 800 cars annually during the 1920s.[iv]

Like many other independent car companies, Franklin folded during the Great Depression, but Hamlin continued to promote automobiles and their related businesses. He organized numerous motor shows and along with Earle C. Anthony and others, established the Los Angeles Motor Car Dealers Association.

Hamlin died in West L.A. on July 5, 1974 at the age of 93. Little remains of his empire. The Flower St. dealership was sold in 1966. The building survived for many years as a wig shop, but was demolished in the early 1980s. However, in a nod to his importance to the Franklin Company, a replica of Hamlin’s flagship was built at the Gilmore Car Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan. The collection includes Franklin automobiles, engines, and artifacts that tell the story of a man whose career defined an industry and the city of Los Angeles.

Notes

[i] “Hamlin Smashed Last Year's Phoenix Record”, Los Angeles Times; Oct 29, 1912; pg. III1

[ii] Smith, Bert C, “Ralph Hamlin in Franklin Leads Race” Los Angeles Times; Oct 28, 1912, pg. III1

[iii] “Ralph Hamlin Returns” Los Angeles Times, Dec 12, 1926; pg. G7

[iv] Powell, Sinclair “The Franklin Automobile Company” Society of Automotive Engineers, Warrendale, PA