Railroads Build – and Destroy: Competing Narratives of L.A. Union Station's Birth

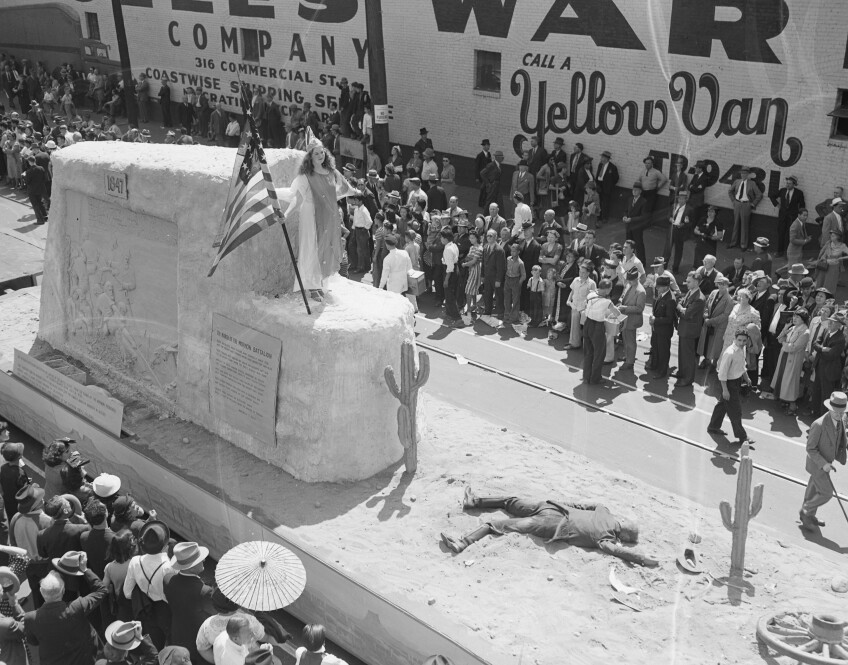

Time rolled on, and shutters clicked. On May 3, 1939, as all manner of wheeled vehicles from Southern California's past paraded down the center of Alameda Street, photographers from the Dick Whittington Studio captured highlights on their four-by-five-inch Kodak film: stagecoaches and covered wagons; wood-burning locomotives and mammoth coal engines; penny farthings and safety bicycles; horse-drawn streetcars and horseless carriages; and a host of modern automobiles.

The procession also featured rail-drawn floats that presented vignettes from a romantically imagined past. On one, children dressed as Mission Indians smiled with baskets of grapes, a scene that elided the realities of exploitative labor and population decimation suffered by Native Californians. On another, a soldier from the Mormon Battalion lay dead next as, above him, a woman waving Old Glory celebrated the armed U.S. invasion of Mexican California of 1847. Tying everything together — the conquered past and the triumphant present — was Hollywood star Leo Carrillo, descendant of a prominent Californio family, who galloped down the parade route and reared his horse for the Whittington photographers.

These images, long hidden away as negatives inside envelopes, are now publicly visible for the first time thanks to a digitization project at the USC Libraries, funded by a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC).

All this pageantry — which attracted one of the city's largest crowds ever, some half a million strong — celebrated the grand opening that week of Los Angeles Union Station, the first passenger terminal to serve all three of the city's major railroads. Even as it looked back in time, celebrating a transportation technology that was already becoming antiquated, the parade held up the new facility as a mark of progress — something Union Station itself embodied through its synthesis of the Spanish Revival and Art Deco styles, all just a stone's throw away from the historic Los Angeles pueblo.

The official theme of the day, announced by a banner draped on the side of the Santa Fe's massive locomotive no. 5006, made the thought explicit, and in the present tense: "Railroads Build the Nation."

At least one group of participants understandably found that slogan too pat. Among the floats that day was one celebrating the construction of the transcontinental railroad, and it featured seven elderly Chinese-American men in period costume — most of whom were, by appearances, old enough to have actually worked on the railroad in the 1870s. The men held pickaxes and sledgehammers and sat or stood along a twenty-foot stretch of replica track. A banner offered a gentle correction to the parade's official theme: "Railroads Built the Nation; The Chinese Helped Build the Railroads."

Those men were not alone in reminding Los Angeles whose backs had carried Los Angeles into the railroad age. Two floats behind them, dozens of Chinese-American men, women, and children — many of them presumably descendants of railroad construction workers — waved the Stars and Stripes and the White Sun flag of the Republic of China. Decades after they had helped open a rail connection between Los Angeles and San Francisco (and hence the rest of the nation) in 1876, the Chinese community remained part of the City of Angels.

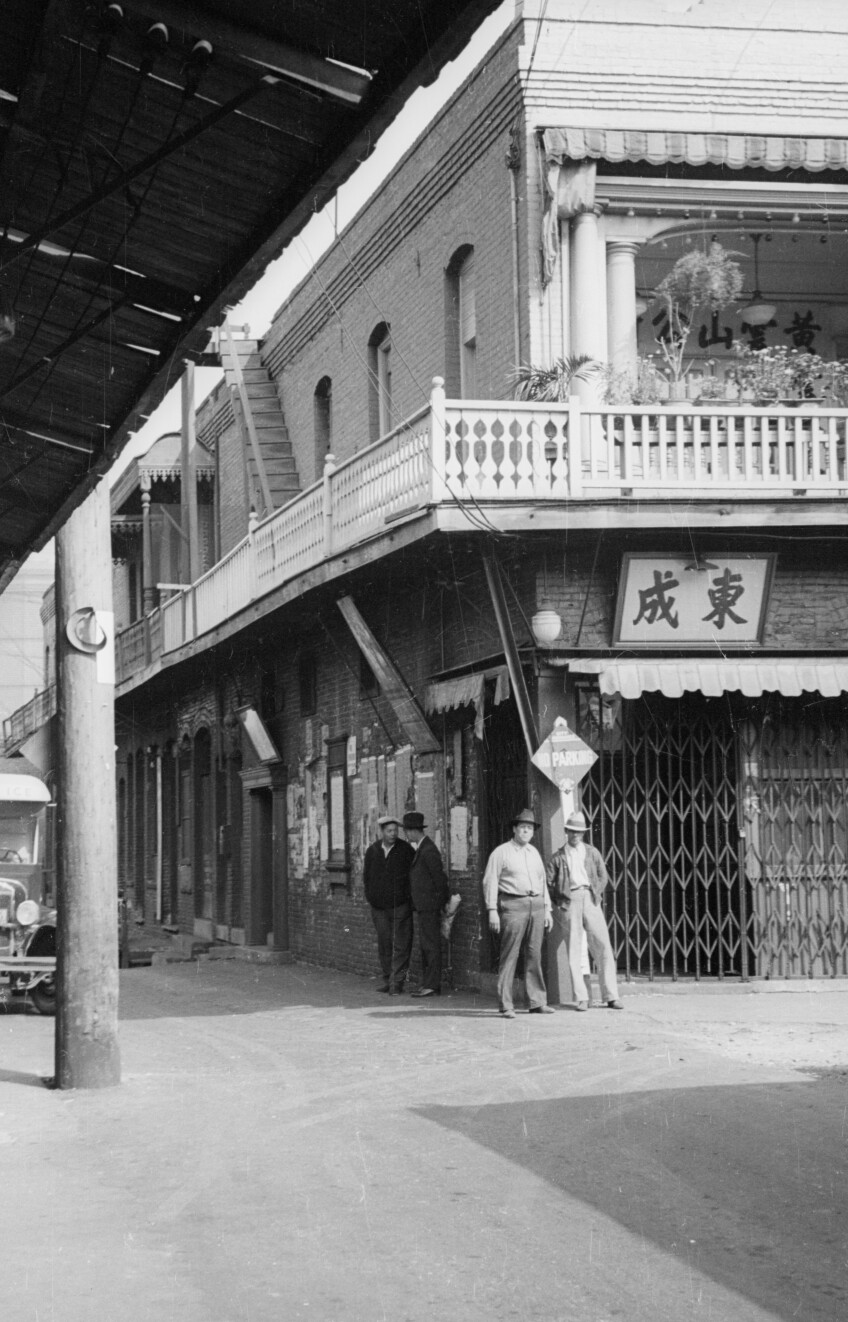

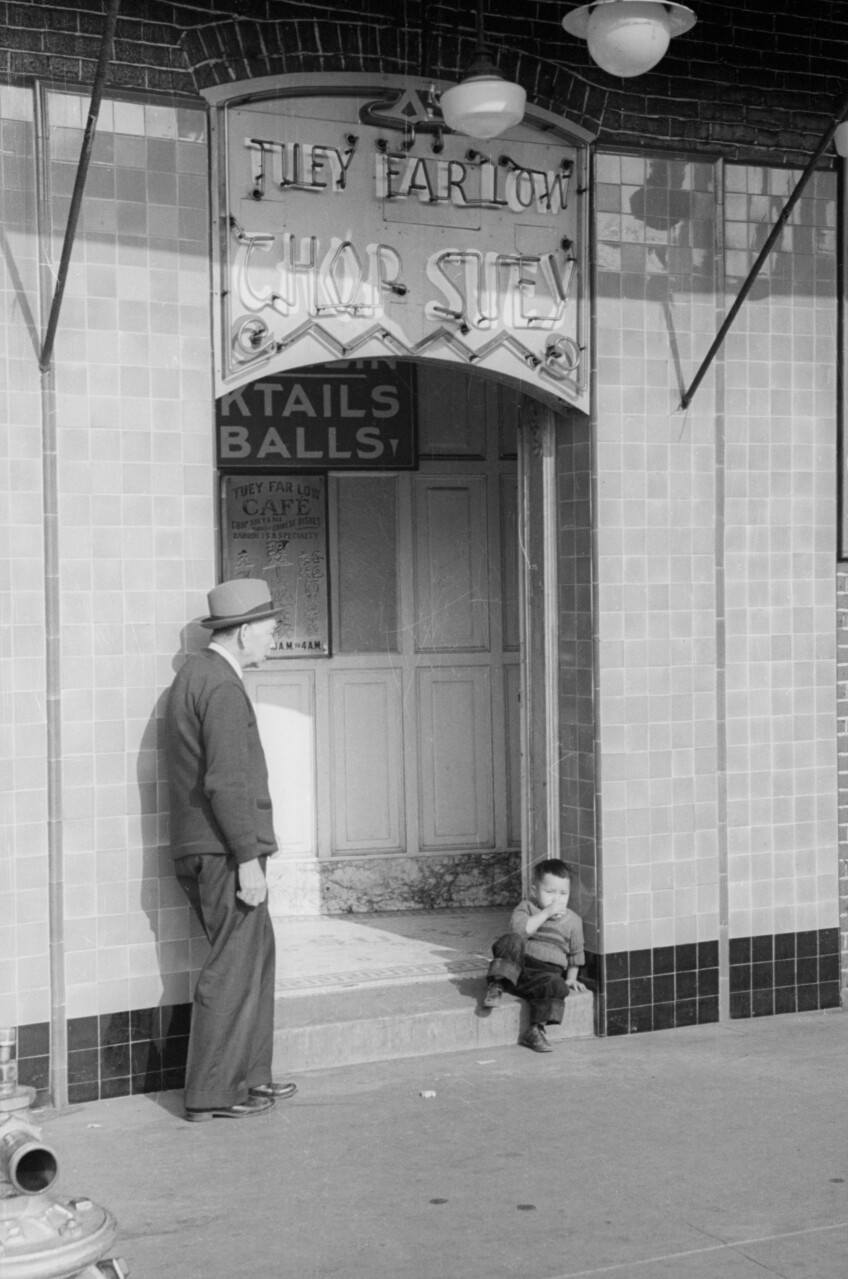

The reminder was especially poignant that day, given the facts behind the construction of Union Station. Before that monument to railroad progress could rise from the east side of Alameda, some three thousand residents of what became known as "Old Chinatown" had to be relocated — some to the "New Chinatown" district just a few blocks to the northwest. Bulldozers and wrecking balls followed. Homes, businesses, and gathering places that had served the Chinese Angeleno community for a half-century were razed.

Railroads build, and railroads destroy.

That loss is indiscernible in the images captured of the parade that May 3, 1939. Whittington photographers were aware of it, however. Sometime before the destruction, probably in the early 1930s, a Whittington operator identified in the files only as "Jack" walked through the future site of Union Station with his 35mm camera. The 15 photographs Jack made — digitized in the 2010s by the USC Libraries as part of an earlier, NEH-funded project — offer a stark contrast with the triumphalism of the later images. Grandfathers stroll with grandsons. A man reads a poster in Chinese script. Boys mug for the lens. No grand spectacle: just the quiet rhythms of everyday life in "Old Chinatown" that would soon be lost to the railroads. The all-too-invisible price of progress.