Promoting the Golden West: Advertising and the Railroad

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

In collaboration with the University of California Press and the California Historical Society, Lost LA is proud to present selected articles from California History that shed light on themes discussed in the show's second season. This article originally appeared in the Spring 1991 edition (vol. 70, no. 1) of the journal.

In these days of color television and lifelike photography, the unique artistry and elegance of rail travel promotion have long since been forgotten. Gone, after all, are America's great trains, those whose arrivals and departures excited daily comment. Explore carefully, then, the following pages. Note how it used to be during advertising's golden age, the period from roughly the tum of the century through the late 1950s. This was the time when all advertisers, including the western rail roads, relied heavily on accomplished commercial artists. The railroads' objective was simple and straightforward–to persuade tourists, potential settlers, sportsmen, and health-seekers to book passage on company trains and coastal steamships. To encourage wanderlust, railroad art and advertising called upon many images, from breathtaking scenery to exotic native cultures, to evoke the desired sensations of mystery, adventure, and innocent romance. In the promotion of California in particular, the western railroads reached into the living rooms of the American public with the assurance that the anticipations of traveling did not lapse west of the Rocky Mountains. In California were wonders galore, from Yosemite and the High Sierra to the rugged Pacific Coast. Every train to California was indeed a magic carpet, a means to one of the most varied and exciting destinations on earth.

Every train to California was indeed a magic carpet, a means to one of the most varied and exciting destinations on earth.

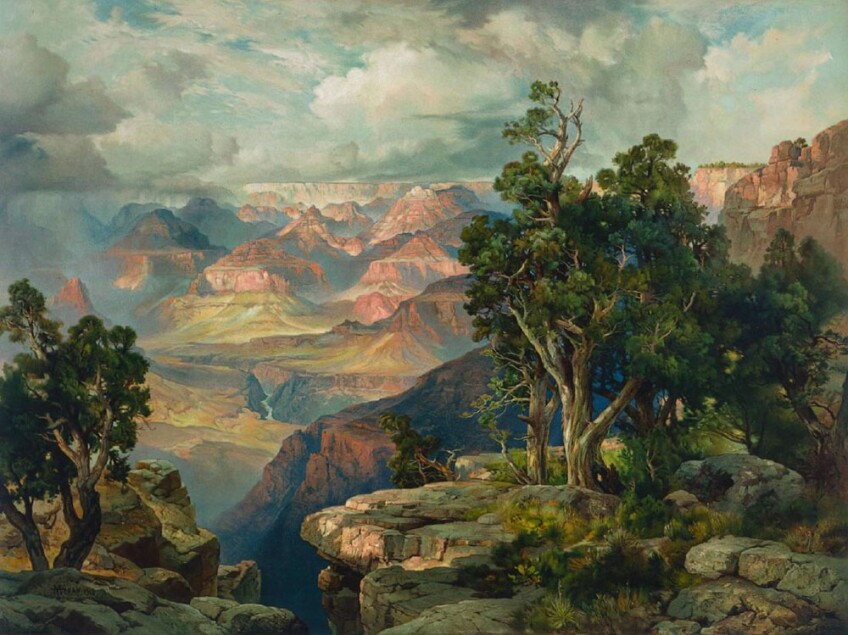

As railroad executives once knew intuitively, the major selling point of their passenger trains was not speed, but rather high adventure. As much as transportation, western trains were an experience. Accordingly, anything that added to the experience, most notably the establishment of national parks, was almost certain to win the support of leading rail officials. Thus, as early as 1871 and the discussion of creating Yellowstone National Park, Jay Cooke and Company, managers and financiers of the Northern Pacific Railroad extension project, evinced a strong and growing interest in rail travel promotion. A $500 loan from Cooke to the renowned painter Thomas Moran-allowing the artist to travel through Yellowstone-may be said to have launched the Northern Pacific's distinguished promotional work.1

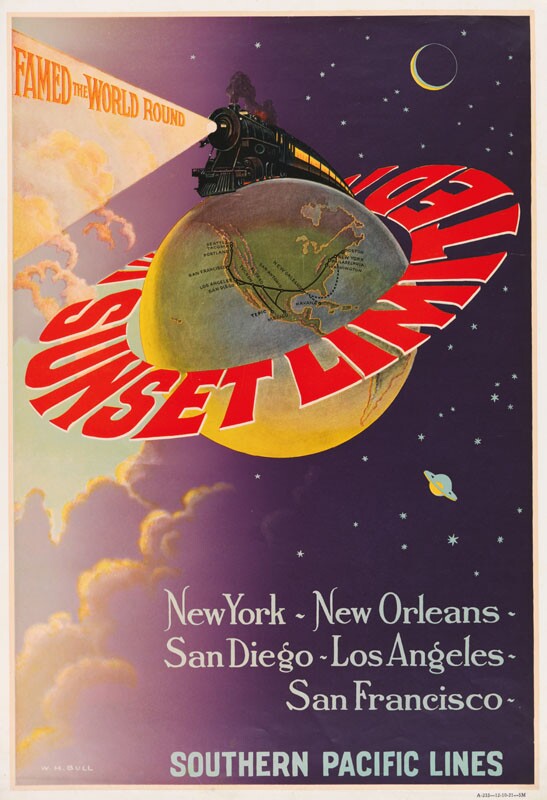

In 1892 the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Rail way also invited Thomas Moran west to paint the Grand Canyon. Although the Grand Canyon would not receive protected status until 1908 as a national monument, the Santa Fe Railroad, like the Northern Pacific, proved instrumental in bringing another western wonderland to public attention.2 So too, in California, the Southern Pacific Railroad began promotion on a grand scale in 1898 with the publication of Sunset magazine, under the direction of the company's passenger department. True to form, the very first issue, published in May 1898, featured Yosemite Valley, which the railroad had already been promoting for several decades.3 Indeed, there is now little doubt that the Southern Pacific Railroad also figured prominently in the establishment of the national park around the valley in 1890.4 As John Muir himself admitted to the Sierra Club at its annual meeting in 1895: "Even the soulless Southern Pacific R.R. Co., never counted on for anything good, helped nobly in pushing the bill for this park through Congress." 5

For the next quarter century, the western railroads loosed a flood of stationery, postcards, calendars, timetables, guidebooks, and advertisements, each in some way distinctly representative of regional scenery and culture. Although people were unaware of it at the time, the peak in railroad travel was finally reached just prior to World War I; when rail travel promotion resumed after the war in the early 1920s, automobile travel was already making serious inroads into rail passenger service. No matter, the railroads at least held their own during the decade. But then came the disruption of rail service caused by the Great Depression and the demands of World War II. Consequently, not until the late 1940s were the lines fully prepared to attempt recapturing the business they had long since lost to America's love affair with the private car.

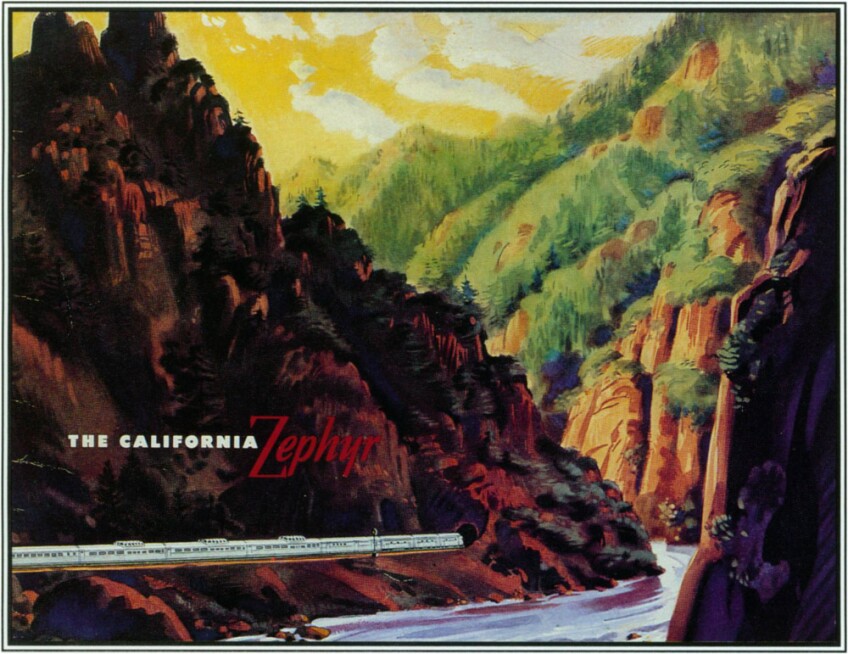

Their efforts were nonetheless sincere and monumental. By the early 1950s the western trains had been completely reequipped with new sleepers, coaches, diners, and-most significant of all-vista-dome lounges and coaches. Predictably, railroad promotion itself returned in all its color and elegance. Once more advertising focused on western scenery and the national parks, further highlighting the trains themselves as magic car pets of romance and adventure. Perhaps the country's all-time favorite train was the new California Zephyr, inaugurated in 1949 asa joint venture of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, the Denver, Rio Grande & Western, and the Western Pacific rail roads. Its 2,000-mile journey from Chicago to Oakland included such breath-taking scenery as Colorado's Front Range and California's Feather River Canyon. Well into the 1950s, the California Zephyr set the standard for.the restructuring and redesigning of every classic western passenger train.

By 1960, the vista dome in particular was standard equipment on every major route. "Look Up; Look Down; Look All Around," the Zephyr itself proudly admonished its patrons. Truly, in the invention of the vista dome, the western railroads had found the perfect marriage between the best in regional scenery and the best in rail passenger design.1

But suddenly, that heritage became history. Virtually overnight, America's railroads had a change of heart about their passenger business. Put simply, the trains failed to make a profit on all but the most popular routes. It was partly, critics charged, the railroads' own fault. They scrapped many basic amenities and the lure of adventure advertising just as their new equipment and pro motions were starting to work. In either case, even among the few western railroads still committed to rail passenger service, only one or two name passenger trains survived by the end of the 1960s.

Since May 1, 1971, a nationwide rail passenger network has survived under the National Rail road Passenger Corporation, popularly known as Amtrak. In testimony to the continuing popularity of its long-distance western routes-now rented from the original railroads-fully three-fifths of all Amtrak revenues are generated outside city corridors. In the West, the average distance traveled is 1,000 miles; in the Northeast Corridor between Washington, D.C., and Boston, it is barely 100. In other words, ridership in the West is ten times more lucrative per passenger than ridership in the Northeast. To be sure, the twenty percent of Amtrak's business that generally travels in the West and South is worth far more to the company than all of the rest of Amtrak's riders combined.7

If Amtrak were a private corporation, its response would be obvious-to place its greatest emphasis on the long-distance trains, those that are the least sensitive to delays, operating constraints, and air line competition, but that still generate the largest revenues. But Amtrak is quasi-public, not private. Its management feels compelled to invest in potential voters as well as self-supporting riders. As long as half of Amtrak's total ridership comes from the Northeast Corridor, politics more than economics will determine which portion of the country receives the most service.8

Perhaps this scenario was inevitable; still, rail passenger enthusiasts cannot help wondering what would happen if Amtrak gave the western trains the attention their historic significance suggests they in fact deserve. The western trains are already sold out for the summer season months in advance. No less than in the past, tourists heading west by rail revel in the beauty of the landscape, in the life and changing kaleidoscope of new people and places. Granted, the riders are modem, but their emotions and expectations are very much the same. It follows that the heritage of discovery, not simple economics, is Amtrak's true hope for profitability and viability in the years to come.

California in particular is still fortunate to enjoy some of the best of Amtrak's trains. Although bear ing little resemblance to the original configuration of five vista domes (and no longer routed through the Feather River Canyon), Amtrak's version of the California Zephyr remains one of the most popular rides in the country, offering the American River Canyon, Donner Pass, Donner Lake, and the Truckee River Canyon in grand compensation for its historical passage of the Sierra farther north. Similarly, the Coast Starlight, operating between Los Angeles and Seattle via Oakland, parallels the rolling breakers of the Pacific Ocean for 110 miles between Oxnard and Surf, California. Sixty and more years after Maurice Logan produced evocative paintings for Southern Pacific Railroad pamphlets, the coast route continues to thrill more than a half million rail passengers annually.9

The point again is that traveling by rail is still considered by its patrons to be an experience. So too, the examples of railroad art reproduced on these pages have long been referred to as "experience advertising." The financial motives of the railroads and the practical uses of rail travel for the passengers are deliberately absent or understated. It is the scenes, the experience, that are meant to do the selling

Such attempts at understated selling are still common to the travel industry; however, color photographs have replaced paintings as the primary means of illustration. Lost, as a result, is some thing of that former sense of anticipation, that wonderful feeling of fantasy that only works of art can fully arouse. Unlike modern photography, the paintings of yesteryear heightened one's expectations of mystery and romance. Photography can be too revealing, robbing its subject matter of all powers of suggestion. Such is the price of accuracy. Indeed, with tour ism everywhere on the rise, transportation companies might well reconsider those colorful lessons from the past.10 Tourists still seek romance and high adventure. When the railroads of North America knew how to market such intangibles, profits rather than losses were consistently the rule. Only the commitment to imaginative advertising, not the public's appreciation of it, has somehow slipped away. It follows that the road back to profitability -and adventure-lies in the truth of that once familiar slogan: "Getting there is half the fun."

Railroad Advertising of the Far West: A Portfolio