Policing a Global City: Multiculturalism, Immigration and the 1992 Uprising

After nearly thirty years of struggle and continued efforts to be more inclusive and diverse, the country is once again in the throes of unrest, clamoring for real change. As the nation strives for answers and ways forward in the wake of George Floyd’s death, it is helpful to look back. How did we get here? How can we help make lasting changes? Read on to learn more.

“April 29, 1992” from Sublime’s 1996 debut album opens with a radio transmission from a panicked LAPD officer. “I don't know if you can, but can you get an order for Ons, that's O-N-S, Junior Market, the address is 1934 East Anaheim, all the windows are busted out,” he reports. “[I]t's like a free-for-all in here and uh the owner should, at least come down here and see if he can secure his business. If he wants to.” The transmission encapsulates some of the most obvious aspects of the 1992 Rodney King Uprising: the LAPD’s inability to respond effectively, the looting that unfolded and the small businesses, notably those owned by Latino and Korean Americans that were victimized.

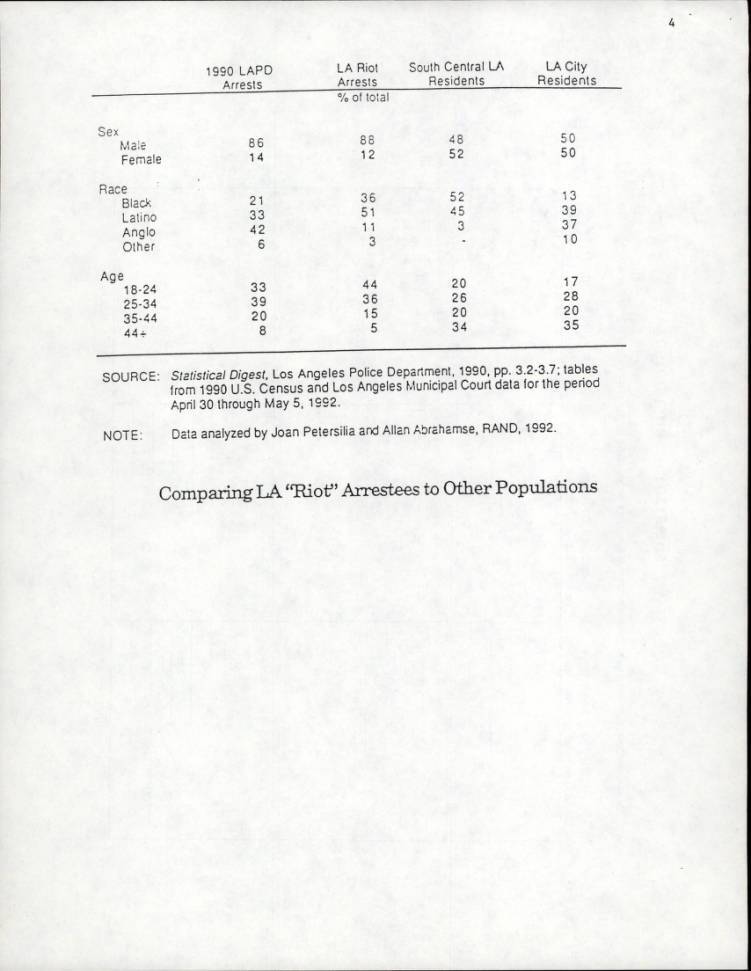

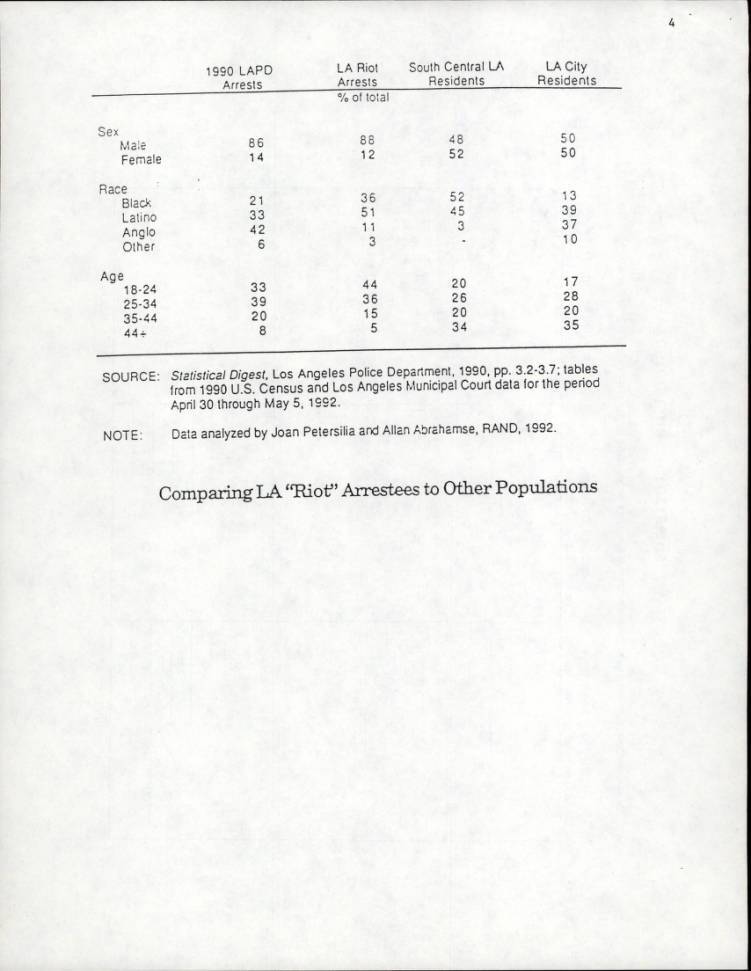

Admittedly, one does not normally look to a ska-punk band for sociological breakdowns of urban unrest, but the Long Beach outfit put its finger on something very real: the uprising, as Tim Rutten wrote in 1992, was “the nation’s first multiethnic urban riot, one that involved not simply the traditional antagonism of one race toward another, but the mutual hostility, indifference and willingness to loot of several different racial and ethnic groups.” Of those arrested by the LAPD over the course of the unrest, roughly one-third were Black, half Latino and the remainder, mostly White. “[C]lass, not race, constituted most of the tensions that led to the riot,” Department of Justice’s lead investigator into civil rights violations in the Rodney King Case, Wayne A. Budd told reporters in May of 1992.

If one accepts both Rutten and Budd’s points regarding the diversity of the riot’s participants, others, such as the University of Southern California’s George Sanchez, add that it also fit into long history of “anti-immigrant vigilantism” in California. Between 30 and 40% of the businesses damaged in the riot were owned by Latino residents; Koreans too bore the brunt of the looting with over $400 million in losses. Though the assault on truck driver Reginald Denny captured the nation’s attention, 30 other people were beaten at the same spot, “most of them pulled from their cars requiring extensive hospitalization,” nearly all of them of Latino or Asian descent, writes Sanchez. Complicating matters further, many Latinos participated in the looting with their neighbors.

How did economic downturn and immigration intersect during one of the nation’s most notorious examples of twentieth century unrest? Importantly, what role did the LAPD play in the uprising’s outcome and how did the department’s policies shape how native-born Americans viewed immigrants in Southern California?

Southern California and the Hart-Celler Act

The demographics of 1992 Los Angeles begin nearly three decades earlier with the passage of the Hart-Celler Act in 1965. Passed in an effort to both eliminate quotas from earlier laws that many viewed as prejudiced and to draw more European immigrants to American shores, the act resulted in far many more newcomers of Asian, West Indian and African descent. For Southern California, the state’s Asian population, which dates back to the nineteenth century, exploded. Between 1973 and 1990, Southern California’s Chinese population increased by almost seven-fold. During roughly the same period, hundreds of thousands of Koreans also made the region their home. In 1970, only 7,000 Koreans resided in Los Angeles County, by 1990, that number had risen to 145,000 and 600,000 in the larger Southern California region. After the Vietnam War, Vietnamese and Cambodians, many of them refugees, also decamped for the Golden State in large numbers.

The immigration act, when combined with post-1945 segregation and the eventual shift to “class-based zoning,” resulted in “new communities of racial interaction” in urban centers across the nation, placing Black, Latino and Asian Americans in close proximity residentially and commercially. This proved more common in newer western cities than those in the Midwest or on the East Coast and Los Angeles, arguably, served as the purest distillation of such developments. For example, nearly half of Koreatown’s residential population was actually Hispanic. Despite depictions that present both as exclusively Black communities, in Watts and South Central, African American and Latino residents shared the community. Korean entrepreneurs established businesses in the two neighborhoods particularly after Jewish merchants left in the years following the unrest in Watts. Interactions between these groups gained greater salience and frequency as demographic and neighborhood change washed over the city in the ensuing decades leading up to 1992.

More on a Nation in the Throes of Change

Ironically, the 1965 immigration law penalized immigrants coming from Mexico when it placed hemispheric restrictions on migration. Prior to its passage, migration from Latin American countries to the U.S. was largely unrestricted. The act’s provisions practically created the category of “illegal alien.” The distinction is equally important for how it shaped how some Americans came to view Mexican Americans and other Latin American nationalities; lumping native born and naturalized persons of Latino descent into collective illegality despite the fact that by 1990, of the over 3,300,000 Latinos in Los Angeles county, only 7% could be considered undocumented or “illegal.”

To be clear, Mexicans have long lived in the region well before and well after it became Southern California. Still, the increase in numbers of Latino residents from 1980 to 1990 was stark. During the decade, Los Angeles County added 1.4 million new residents; 93%, were Latino. Economic struggles and expanding inequality in Mexico drove many nationals to migrate north. Mexico City, once a prime destination for rural Mexicans and Central Americans, could not absorb the rise in migration. U.S. interventions in Central America predictably created havoc for residents of Nicaragua and El Salvador and destabilized the larger region, which resulted in increased immigration to Southern California. By 1990, 300,000 Salvadorians and nearly 160,000 Guatemalans resided in the city; a five-fold increase for both from 1980.

As more than one writer noted, by the end of the twentieth century, Los Angeles International Airport had transformed into the nation’s “new Ellis Island.”

In 1988, nearly 14% of new immigrants to the country settled in Los Angeles; in 1990, almost one third of the city’s population had been born abroad.

Worries about immigrants exploiting the nation’s resources became commonplace. The Los Angeles Times blamed local budget issues on increased immigration as one headline read, “Aliens Reportedly Get $100 Million in Welfare.” David Rieff’s 1991 work, “Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World” furthered such attitudes in his depiction of the city as fragmented and awash in “mutual incomprehensibility.”

To critics’ points about immigration, notably undocumented residents, there were costs. By 1993, 23% of the Los Angeles Unified School District’s budget of $6.5 billion went to bilingual education. Governor Pete Wilson alleged that illegal immigration along with residents amnestied by the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, cost the state $1.5 billion every year. By 1993, undocumented immigration rose to three times its counterpart. Senator Diane Feinstein argued that 2.3 million undocumented immigrants resided in California, a figure that made the state home to over 50% of undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

Evidence also suggests that some groups, some Southeast Asian groups for example, did initially turn to welfare, but that others, notably Latinos, decidedly did not. “Latinos, immigrants especially, were by far the least likely to be on any form of public assistance,” noted California historian Kevin Starr.

In recent years, researchers have shown that refugee populations, similar to the Vietnamese, Cambodians and Hmong that settled in California during the 1970s following the Vietnam War, and immigration more broadly might prove costly upfront but result in long term rewards such as low level gentrification, increased economic activity and lower crime rates. In 1992 however, nuance on the subject frequently evaporated into angry or accusatory policies, statements and headlines.

The LAPD and Immigration

The LAPD’s policing of immigration helped to shape public opinions regarding the status of the region’s newer arrivals. By the 1970s, the LAPD routinely rounded up undocumented Mexican immigrants and handed them over to Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS, a precursor to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement). In addition, it created the categorization of “alien criminal,” which actually preceded the INS’ creation of a similar category in 1986 with its Criminal Alien Program. “Aggressive immigration enforcement thereby treated all Mexican American residents as perpetual foreigners,” writes historian Max Felker-Kantor. “By constructing a racialized category of the ‘alien criminal’ as any ethnic Mexican in need of supervision, the LAPD … expanded its authority to enforce order and define exclusionary boundaries of citizenship.”

"Injustice can provoke African-American rage, not only against white authority, but against, ‘racialized others'"<br>George Sanchez

To be fair, crime statistics during the 1980s and into the early 1990s were alarming, particularly in Los Angeles. Between 1969 and 1989, violent crime trebled and Los Angeles’s incidents exceeded the national average by a factor of two. The paramilitary approach adopted by the LAPD to crime framed by slogans such as “The War on Gangs” and “The War on Drugs” served to address this rise in crime, defenders asserted.

The LAPD instituted Special Order 40 in 1979 to curb the department’s involvement in policing immigration by making arrests based on immigration status beyond an officer’s jurisdiction. Yet in reality, the LAPD continued to work jointly with the INS during the 1980s, and critics argue this relationship collapsed their approach to both gangs and drugs as a means to police immigration. A 1988 task force consisting of the LAPD, INS and Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department focused on undocumented gang members for deportation even when not charged with a crime. The problem was not so much that all undocumented individuals were innocent of drug crimes but rather the status of “gang member” proved fluid in LAPD definitions, meaning numerous individuals were categorized incorrectly, despite having little or no connection to gangs.

Legitimate evidence and investigation-based raids morphed into immigration sweeps. As Antonio Rodríguez of the Latino Community Justice Center noted following a 1989 raid, the police “may apprehend some criminals, but they target and capture in their net many innocent persons who are taken prisoner by INS agents.” Even the LAPD’s less sensational decisions regarding immigration, such as the crackdown on street venders beginning in the early 1980s, sent a similar message. Commander Rick Barton of the LAPD attested to this fact. “The thing is most of these people are Latinos — from Mexico, (San) Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras and who knows how many of them are undocumented. So even though the INS has no part in this task force, it could be that a lot of them are afraid we might have the INS with us.”

From a purely procedural perspective, such strategic decisions overburdened the criminal justice system and led to civil rights violations for Americans of Latino descent. Historians such as David Gutiérrez have shown many Americans fail to distinguish between Latino American citizens and undocumented residents lumping them all into a single category thereby subjecting the former, in particular, to civil liberties and civil rights violations. It also placed the city council at odds with the LAPD; the council declared Los Angeles a sanctuary city in 1985.

1992

Throughout the 1980s, federal funding to cities declined as more and more municipal governments adopted neoliberal policies which at the risk of oversimplification advocated for tax abatements to businesses and corporations, public private partnerships for public works, and the reduction or elimination of public pensions. Typically, such policies disproportionately affect the working class and poor. In Los Angeles’ case, Mayor Tom Bradley pursued Pacific Rim investment spending municipal dollars on the city’s airports, harbors and downtown at the expense of Los Angeles’ struggling neighborhoods.

As 1992 approached, the nation fell into a recession and Los Angeles suffered not only the same economic downturn but also the retreat of local industry to other parts of the American Sunbelt or to other nations with cheaper labor costs.

"The city today is like the Balkans, rich with blood feuds that outsiders can scarcely understand”<br>John Gregory Dunne

The combination of reduced federal funding and deindustrialization struck Black Los Angeles harder than arguably any other population in the city. From 1973 to 1986, average yearly earnings for young Black high school graduates declined 44%. Extend the period three more years to 1989 and one finds that average earnings for Black men dropped 24% while unemployment rose to record levels. Poverty rates for families living in South Central, many of which were not only Black but Latino, ranked twice that of the city’s overall rate and nearly a third higher than just before Watts.

Meanwhile as heavy industry left, the low wage garment industry developed particularly in Southeast Los Angeles. In the three years before April 1992, the city shed 150,000 manufacturing jobs. From 1979 to 1989, of all the new jobs created, 40% paid under $15,000 per year, and most of this employment went to newly arrived immigrants hailing from Mexico, Central America, and Asia. Even with employment, poverty rates among Latinos from 1969 to 1989, especially among the foreign-born, increased from 17 to 23%. Between 1973 and 1986, Latino earnings diminished by 35%.

More generally, inequality between Anglo residents and others widened as median household net worth for Anglos in the city was $31,904; for non-Anglos, $1,353. For all the hardship endured by Black Los Angeles, their proportion of the city’s population living in poverty declined from 24% in 1969 to 18 in 1989 while Latino L.A. increased its share of this demographic from 22% to 57%.

At the same time, Mexican and Central Americans moved into Watts and South Central, which by 1992 had become significantly, if not predominantly Latino. Korean storefronts operated in both and relations between African Americans and Korean store owners frayed due to several factors including the shooting of Latasha Harlins by the wife of a storeowner, the killing of two store workers by a black robber and boycotts by local African American leaders demanding Black-owned retail. “The city today is like the Balkans, rich with blood feuds that outsiders can scarcely understand,” John Gregory Dunne wrote in the New York Review of Books in October 1991.

Dunne appeared prescient when violence erupted after the Rodney King verdict on April 29, 1992. The unrest demonstrated not only the anger over police brutality that simmered beneath the surface, but as author George Sanchez argues “that injustice can provoke African-American rage, not only against white authority, but against, ‘racialized others,’ most notably Asian and Latinos living among blacks in newly ‘reintegrated’ communities.” City council member Nate Holden, who is African American, told investigators after the uprising that the nation’s borders needed to be closed because the city could not absorb any more foreigners, noting that all his constituents be they Black, White or Brown felt similarly.

Property damage from the uprising occurred in communities that had transitioned from Black to Latino though it was not shared evenly as “damaged areas” were nearly 50% Latino and 37% Black. Of the 58 individuals violently killed during the unrest, the vast majority resided in these communities. The longer established East Los Angeles remained untouched while newer immigrant enclaves such as Pico-Union and Westlake suffered damage.

View pages from the 1992 RAND report on the Uprising by clicking on the arrows below.

When Pico-Union’s city council representative, Mike Hernandez, requested National Guard troops to quell the looting, the government sent the Border Patrol. Of the 1,200 “riot aliens” transferred from the LAPD County Jail to INS, 86% of their cases resulted in deportation. East Los Angeles City Council representative Richard Alatorre underlined the separation between the communities. “I will try my best to be advocate for immigrants’ concerns. But I didn’t get elected to represent them,” he commented at the time. “I have a responsibility to the people I happen to represent.”

During the unrest, the LAPD abandoned Koreatown along with other minority and low-income communities, drawing a perimeter the stopped at Pico-Robertson and prevented the spread of unrest to Beverly Hills. Then President-Elect of the Korean American Bar Association and Los Angeles native Angela Oh worked the phones at the Korean American Community Center as storeowners called in frantically. The city’s Korean American radio station operated as an emergency network though which calls for help by storeowners went out. Toyota Land Cruisers brimming with armed Korean men patrolled Koreatown’s streets. Edward Jae Song Leewould be the lone Korean American death when killed by cross fire, mistakenly shot by a fellow Korean American.

As Elaine Kim wrote in Scott Saul’s “Gridlocks of Rage,” the civil disturbance both served as “a baptism into what it really means for a Korean to become an American in the 1990s,” and a reminder of the state, city and nation’s long history of violence toward Asian Americans. Economically, the looting struck a crushing blow to the Korean American business community, one third of which operated in Koreatown. The average Korean business owner carried debt between $200,000 and $500,000. Like many minority entrepreneurs at the time, these businesses often had no insurance or were underinsured. A total of 300 Korean American businesses burned during the unrest and clearly, liquor stores, small groceries and gas stations in South Los Angeles had been targeted.

However, though Korean American relations with African Americans had frayed, a significant portion of the looting that victimized Korean entrepreneurs was done by their Latino neighbors. “[M]any of the most hard pressed Latinos — poor immigrants who had fled poverty or political terror in Mexico and Central America, settled in overcrowded apartments in South Central or Mid-City, and taken subminimum wage jobs to support their families — enthusiastically availed themselves of food, clothing, diapers, and other goods,” Saul noted. Several observers pointed to the history of trauma and poverty endured by Central American immigrants to explain the looting and its “shopping spree-like” atmosphere.

After the uprising as part of the Webster Commission investigating the event, José Lozano, then publisher of the city’s largest Spanish language newspaper, La Opinion, admitted he feared future violence telling investigators it would not be directed at Whites but rather between African Americans and Latino and Asian immigrants as a gulf of misunderstanding existed between the groups. Anti-immigrant sentiment pervaded Southern California — perhaps exemplified by Governor Pete Wilson’s anti-immigrant/anti-Latino Prop 187 referendum, which drew the support of even liberals such as Senator Diane Feinstein. In a 1994 statewide poll, 25% of all immigrants expressed fear over discrimination or violence due to their appearing foreign to native-born Americans. Their fears proved very real when hate crimes increased by 17% between 1995 and 1996.

Though it arguably got worse before it got better, both attitudes about immigration and LAPD policies evolved. To the former, organizing shifted from “ethnic identification to a more community and labor-oriented strategy,” notes Manuel Pastor. Organizations like AGENDA and the Community Coalition, both established in South Los Angeles, “were multiethnic from the get-go” focused on forging coalitions based on economic and quality of life issues.

To the latter, after a series of scandals, the federal government intervened with a consent decree forcing reform on the department. The LAPD’s demographics have radically changed as well. In 1992, nearly 70% of the department was White. Today, 60% of its officers are minorities. While Felker-Kantor and others point out that diversifying police forces, due to larger structural issues, does not guarantee better law enforcement or an end to abuses, others believe it still holds value. Prominent civil rights attorney Connie Rice, who spent much of the 1980s suing the LAPD, believes it makes a difference. “They’ve gone from an openly racist and misogynist subculture that they had, controlling the majority culture, for at least 50 years,” she told the New York Times in 2018. “Over the last 20 years, that is what we have exorcised, after the Rodney King riots.”

Finally, big city departments typically eschew policing immigration. Numerous police chiefs across the United States argue such policies actually inhibit policing since it alienates immigrant communities and results in fewer coming forward to report crime. In 2019, LAPD refused to participate in ICE raids on undocumented residents.

“Cause everybody in the ‘hood has had it up to here/It's getting harder and harder and harder each and every year,” Sublime’s Nowell croons. Economics and a disingenuous overly zealous LAPD — “It wasn't about Rodney King,” he declares, but rather this “fucked situation” and “these fucked up police,” — explain what happened on April 29, 1992. The Long Beach band might not have been experts on policing, immigration or the LAPD, but, in the end, they weren’t that far off.

Suggested Readings/Works Consulted

Davis, Mike. "Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the City." New York: Verso, 2000.

Dunne, John Gregory. “Law & Disorder in Los Angeles.” New York Review of Books, October 10, 1991.

Felker-Kantor, Max. "Policing Los Angeles: Race, Resistance, and the Rise of the LAPD." Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Gutiérrez, David. "Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity." Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Hackworth, Jason. "The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism." Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007.

MacDonald, Susan Peck. “The Erasure of Language.” College Composition and Communication 58, no. 4 (2007): 585-625.

Meraji, Shereen Marisol. “As Los Angeles Burned, the Border Patrol Swooped In.” Produced by NPR. Code Switch. April 27, 2017. Podcast, MP3 audio, 00:08:00.

Pastor, Manuel. “Contemporary Voice: Contradictions, Coalitions, and Common Ground.” In "A Companion to Los Angeles," edited by William Deverell and Gregory Hise. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Rutten, Tim. “A New Kind of Riot” The New York Review of Books (June 11, 1992).

Sanchez, George “Face the Nation: Race, Immigration, and the Rise of Nativism in Late Twentieth Century America.” International Migration Review 31, no. 4 (Winter 1997): 1018.

Sassen, Saskia. "The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo." Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Saul, Scott. “Gridlocks of Rage: The Watts and Rodney King Riots.” In "A Companion to Los Angeles," edited by William Deverell and Gregory Hise. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Sides, Josh. "L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present." Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003.

Starr, Kevin. Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003. New York: Vintage Books.

The project to digitize the records from the Los Angeles Webster Commission has been made possible by a major grant to the USC Libraries from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor.

Top Image: "Understanding the Riots," a Los Angeles Times publication containing photographs, testimonies, and descriptions of events before, during, and after the Rodney King riots, cover, 1992. | Los Angeles Webster Commission records, 1931-1992, USC Libraries