Operation Bootstrap: Empowering the African American Community through Entrepreneurship

A police stop of a black motorist may have set off the 1965 Watts Riots, but segregated schools, joblessness and poverty have widely been identified as the social factors that drove residents of this South L.A. community to take to the streets and resist. For six days beginning on August 11, community members overturned cars, set fires and confronted police. In the end, 34 people died, 1,000 suffered injuriesand property damage topped $40 million. The massive devastation left in the rebellion’s wake led to hopelessness about society’s “race problem,” but it also spurred African Americans such as Louis Smith and Robert Hall to take action.

On November 24, 1965, the duo launched an organization called Operation Bootstrap on 4161 South Central Avenue in Watts. It would work to enhance the educational and professional skills of residents and connect them to the career networks that eluded them in South L.A. Fifty-four years after Operation Bootstrap began, the project is most remembered for starting a variety of businesses — namely Shindana Toys — that put community members to work and allowed them to witness economic empowerment through an African American lens. While Operation Bootstrap ended in the 1980s, its contributions to black life reverberate today. The organization emphasized the importance of black entrepreneurship and used its business initiatives to shift public perception of black identity and uplift the community.

While walking down Central Avenue in the late 1960s, a young man named Lewis Kisasi discovered Operation Bootstrap. Seeing a group of people gathered in an empty warehouse piqued his curiosity enough to prompt him to walk inside. Barely out of his teens, Kisasi was welcomed when he stepped into the Bootstrap offices, which had an open-door policy.

"I was excited about the possibility of Operation Bootstrap," said Kisasi, now 75. "Lou was the intellectual powerhouse, and Robert also had great strength. He was more of a people person and was easy to relate to. Right off the bat, people liked his personality and Bootstrap's philosophy of people doing for themselves. That really was the genesis of Bootstrap — to do something for self."

While Operation Bootstrap was certainly a team effort, much of the credit for its success has been given to its charismatic president Lou Smith, who started out in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Born to a Philadelphia police officer and homemaker in 1929, Smith revealed an activist streak when he was just a small child, according to his son, Lou Smith III.

“In fourth grade, his school tried to expel him because he said it was impossible for Christoper Columbus to have discovered America when there were already people there,” his son said. “He wouldn’t come off that, so the school called his parents in for a big meeting. He was an interesting guy. He was a funny guy.”

Smith may have been a nonconformist, but that didn’t stop him from joining the racially segregated armed forces in 1947. Years later, he bragged about flouting military rules, drinking whiskey on the job and farming out his clerical work to his latest romantic conquest, according to the paper “Operation Bootstrap: Beginnings.” But the Army wasn’t just fun and games. While riding in a jeep, Smith suffered a back injury that would cause him chronic pain.

Although he’d hoped to pursue a career as a commercial artist, his career path changed when a friend invited him to a CORE function circa 1959. He quickly became an active member in the Philly chapter and, later, its chairman, according to his son.

“My father always had a sense of fairness,” Lou Smith III said. “He was always for the underdog, and he skyrocketed up the CORE ranks.”

He participated in sit-ins and sleep-ins targeting trade unions and housing programs that excluded African Americans. David Crittendon, a fellow CORE activist, said that the trade union campaigns particularly inspired him.

“It had a huge effect on Lou Smith,” Crittendon said. “He really admired the trade union activists who were asking, ‘Why can’t black workers have the same opportunities as white workers?’ It made him a genuine civil rights activist.”

By 1963, CORE officials asked Smith to go to Mississippi to serve as a leader there. He was in Mississippi the following summer when white supremacists abducted and killed civil rights workers Michael Scwherner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney. Since Schwerner and Goodman were white Northerners, their murders garnered national media attention, but 41 years would pass before anyone was held responsible for the crimes. In 2005, a jury convicted klansman Edgar Ray Killen of manslaughter for the killings.

After the gruesome 1964 murders, Smith headed to California to serve as CORE’s West Coast and Midwest regional director, his son said. His supporters urged him to run for national director of CORE, but Smith enjoyed interacting with the public and loathed the idea of sitting in an office all day.

In Los Angeles, he found a fragmented CORE, with traditional and radical factions who couldn’t agree on the best approach to serving the community. The left-leaning members formed a group called the Non-Violent Action Committee (N-VAC), which met on Central Avenue in the heart of black Los Angeles. In contrast, the established CORE chapter met in the largely white San Fernando Valley. Smith first met Robert Hall at an N-VAC event protesting CORE’s national leadership, but the two didn’t share their philosophies on social justice with each other until the Watts Riots. In the aftermath of the violence, they sat in a cafe and exchanged their ideas about how to better the community.

"South Central Los Angeles — it was an extremely isolated black neighborhood," Crittendon said. "The city was extremely segregated, and there was a real sense of just being shut out and overpoliced living in very poor conditions with very few opportunities to break out of those situations. Say you were a young black teen who wanted to be employed in a department store; you wouldn't get that job. And the aerospace manufacturing companies that had been in South L.A during World War II had moved far away. South Central was left as kind of this desolate area with poverty and poor infrastructure."

Three months after Smith and Hall's brainstorm session, Operation Bootstrap kicked off. With Smith as president, Hall served as executive vice president, and the board included members Woodrow Coleman, Linda Clark, Clarence Price and Sheila Tucker. Working with psychologists and other professionals, Operation Bootstrap identified the Watts community's main needs, primarily jobs and remedial education classes. Via a press conference and leaflets, the organization then publicized its plans to help the deprived neighborhood. A racially diverse mix of groups, including the Pacific Palisades Hadassah, the Soroptimists Club of Alhambra and the Laguna Beach NAACP, offered to help Operation Bootstrap with its mission. In addition, more than 50 volunteers agreed to teach reading, writing and speaking classes to the Watts community. Instructors also led courses on electronics assembly, key punching, and computer programming.

Kisasi, who would eventually become a Bootstrap board member, recalls the organization offering sewing classes and holding community dialogues.

“We’d have these sensitivity sessions where people from various communities, mainly the white communities, would have these dialogues about fixing the problems in the black community,” he recalled.

Operation Bootstrap attracted not only concerned citizens and volunteer teachers but also politicians such as the national Office of Economic Opportunity director Sargent Shriver, California Gov. Pat Brown and Ronald Reagan, who would serve two terms as the state's governor beginning in 1967. Although politicians visited the organization, Smith strongly opposed taking the government's money to support Bootstrap financially.

“All money was raised through personal or public outreach,” Crittendon explained. “Lou Smith, being a very astute activist, realized that there were individuals and communities outside of South Central L.A. who wanted to do something to aid the citizens in the Watts rebellion zone.”

Friends of Bootstrap clubs fundraised enough money to allow Bootstrap to start various business ventures, including the clothing store Bootstrings; daycare and educational center, Baby Bootstrap; the Afrocentric boutique Kiwanda; and even a gas station.

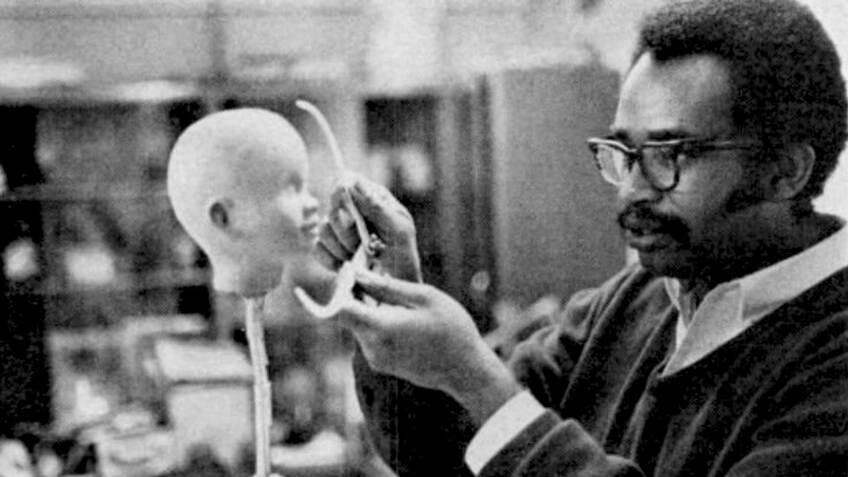

By far, Shindana Toys stands out as the most commercially successful Bootstrap business. In 1968, it opened and became so profitable that it allowed the operation to run almost totally autonomously. An infusion of cash, including a $500,000 loan from Mattel and a collective $1 million in funds from Chase Manhattan Bank, Sears Roebuck & Co. and Equitable Life Assurance, gave Shindana (Swahili for "competitor") a strong start. The toy company featured black dolls, such as "Baby Nancy," with features modeled on actual black children's faces.

“That was the ultimate company,” Kisasi said of Shindana. “It started because of a young black girl who only had little white dolls. That gave Lou the idea for the Shindana Toy Company.”

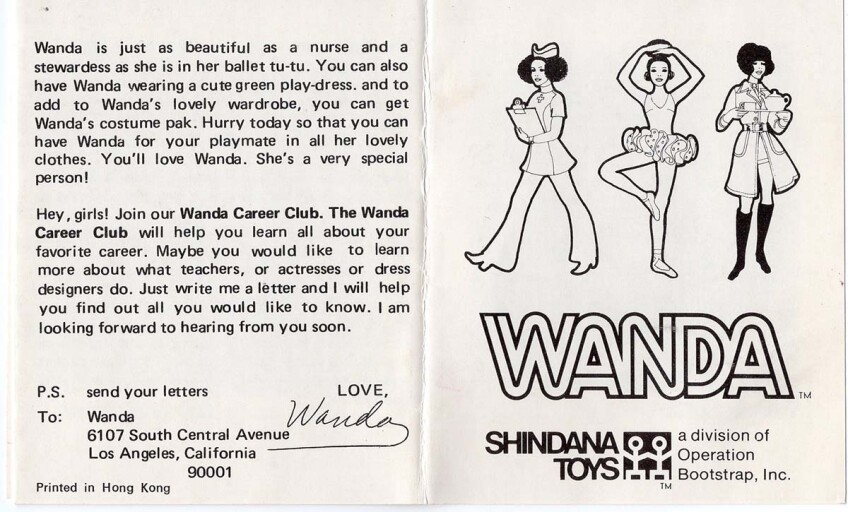

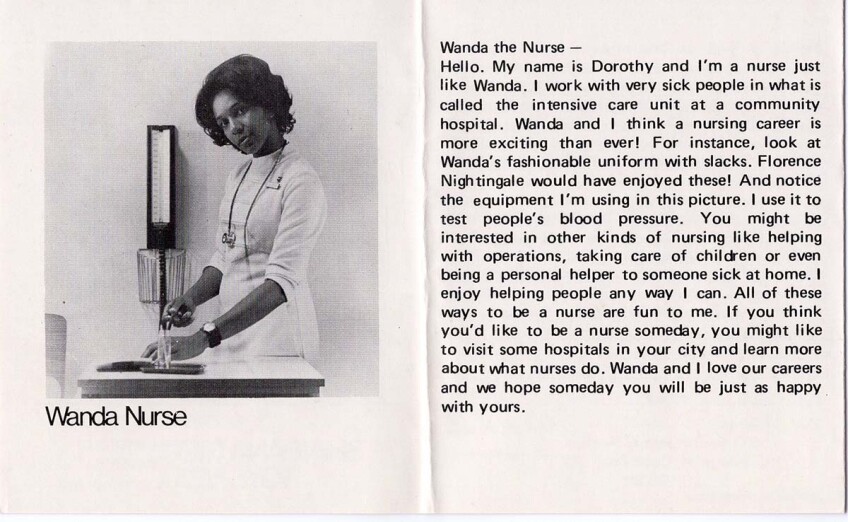

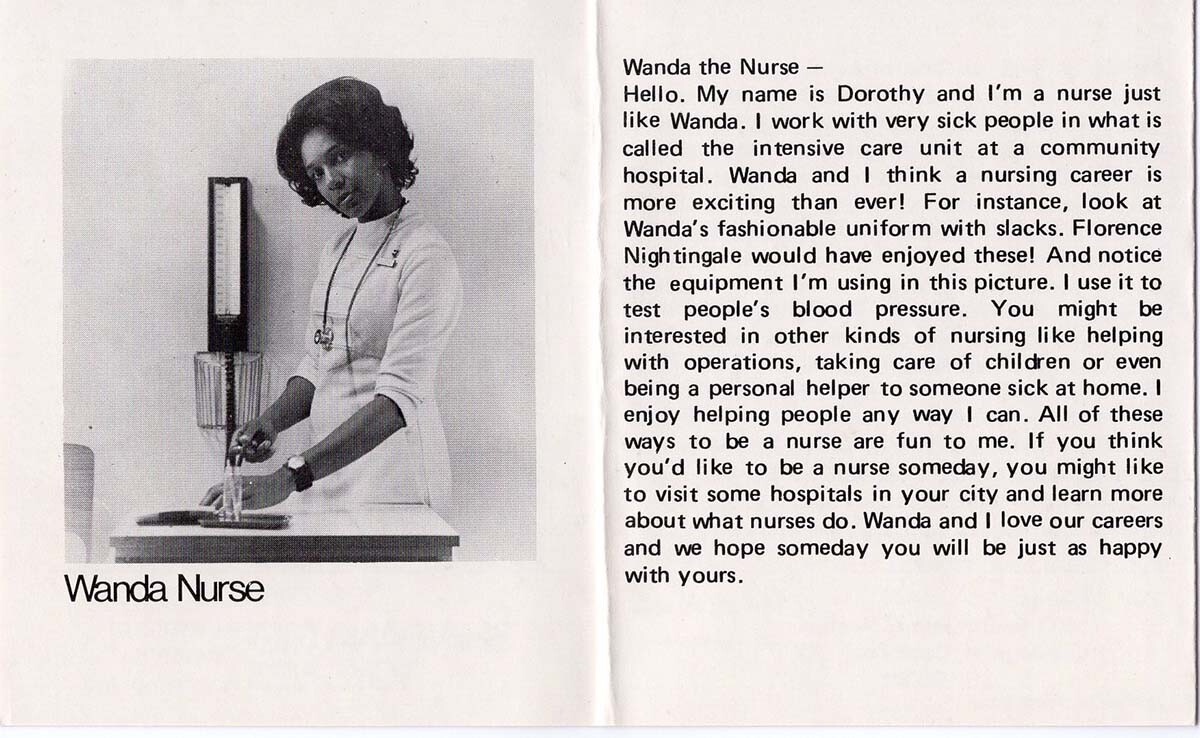

According to the Los Angeles Times, Nancy was the first doll marketed as black by a toy company. Shindana would subsequently debut Asian and Native American dolls in addition to a line based on black celebrities like Flip Wilson and O.J. Simpson. Debbie Behan Garrett, a doll collector and author of books such as “The Definitive Guide to Collecting Black Dolls,” is a fan of Shindana’s career doll line.

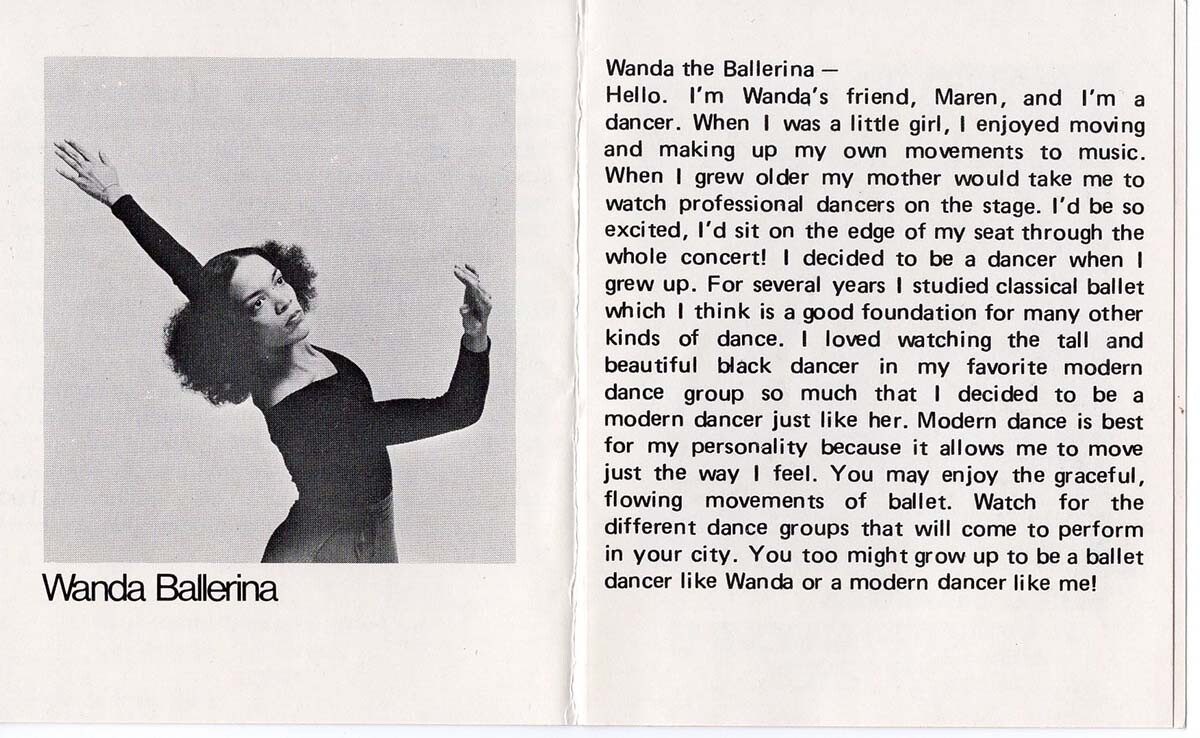

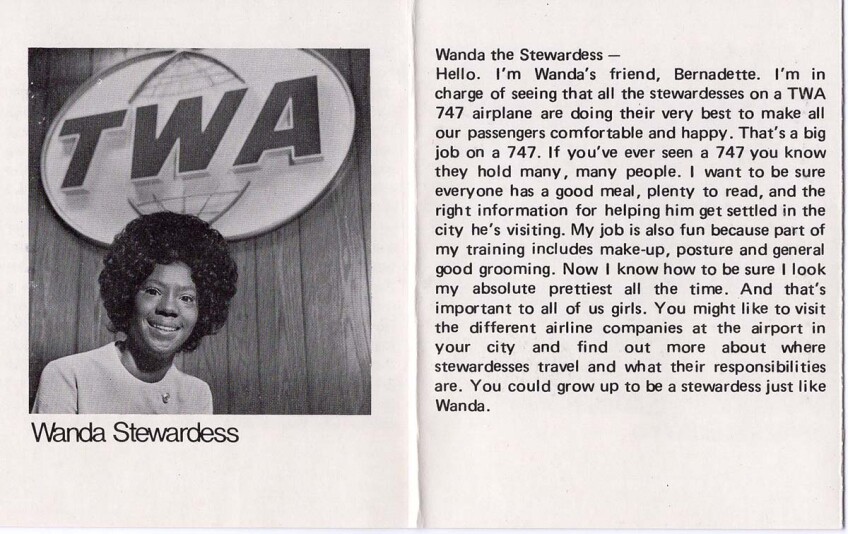

“It represented different occupations to aspire to,” she said. “One may have been a receptionist, another a race car driver or a stewardess or ballerina.”

Click right or left to see some of the career options presented by the Wanda doll:

In the 1960s, realistic-looking black dolls were scarce, with most resembling white dolls in darker hues. Before then, many of the black dolls on the market looked like racial caricatures of African Americans. Garrett said that growing up in North Texas in the 1950s and '60s it was nearly impossible to find black dolls with realistic features. When she discovered Shindana dolls years after they were first released, she felt overjoyed.

“I was shopping at a store that carried overstock or discontinued items, and I saw Shindana’s Baby Janie doll that had ethnically correct facial features that weren’t exaggerated. She had the little pug nose and fuller cheeks and fuller lips. She didn’t have curly hair, but you knew this was not a white doll painted brown. I was so excited.”

During the 1974-75 fiscal year, Shindana earned $2 million in revenues, with sales representatives in major cities across the country. Shindana's success allowed Operation Bootstrap to launch other projects, such as Honeycomb Child Development Center, designed to educate the children of South L.A. while instilling a sense of racial pride in them. But Shindana's huge profit margin would be short-lived. Aware that Shindana was thriving by serving black clientele, rival companies began to sell black dolls of their own, having previously ignored African American consumers desperate to find positive images of themselves. The 1970s recession marked a downturn for both Shindana and Operation Bootstrap, as consumers were less likely to spend their disposable income on nonessentials or donate to social justice causes.

Lou Smith devoted almost all of his time to running Shindana, and Bootstrap faltered without his leadership. Meanwhile, Robert Hall struggled to adjust to the corporate environment of Shindana, which employed 50 to 60 workers. His difficulties resulted in him being asked to resign as the company’s CEO and president. This led to his departure from both Shindana and Bootstrap overall. Just six months after his exit, Hall had a fatal heart attack in 1973 at age 42. Three years later, another tragedy occurred when a car wreck claimed the lives of Lou Smith and his daughter Matilda; Smith was 47.

The loss of Smith hit Shindana hard, but the company remained in business until 1983. With its assortment of dolls of color, the toy company was ahead of its time. Lou Smith knew that representation mattered decades before consumers could easily find dolls in a range of skin tones, body types, and hair textures, as they can currently.

With no black dolls to play with as a child in the 1940s, Portland native Laverne Hall grew up to manufacture a line of black paper dolls, organize a show called LaVerne's Original Holiday Festival of Black Dolls, and publish the DOLL-E-GRAM newsletter about the toys in the 1990s. She applauds Lou Smith for his contributions to black dolls and has presented a “Shindana award” at her former doll show.

“His story was such a marvelous story,” she said of Smith. “The political part of this thing for me is that the major toy manufacturers were making millions of dollars on black dolls that were the same as the white dolls, just painted over. There was nothing authentic about them. While they’re making millions of dollars on us [African Americans], we were not getting anything out of it.”

It’s important for black children to play with toys that resemble them because it fosters self-esteem, Hall said. Shindana recognized this need and became a competitor in an industry that had traditionally overlooked African Amerians.

Laverne did not have the chance to meet Lou Smith in person but described his approach to Operation Bootstrap and Shindana as progressive.

“He was very forward-thinking,” she said. “He was creative, and he didn’t mind stepping out and taking a chance in the interest of his community. Whatever he could do to move his people and his community forward, that’s what he did.”

Without Operation Bootstrap, of course, Shindana would never have come to fruition. Crittendon said it saddens him that both the toy company and the economic empowerment organization behind it have largely been forgotten.

"Bootstrap — it has gotten lost just like a lot of black history gets lost," he said.

But Smith and Hall led lives that deserved to be remembered, Crittendon added.

“Lou Smith and Robert Hall were absolutely unbelievable as individuals,” he said. “They meant what they said and showed it in their actions. They walked their talk, and that made all of the difference.”

Top Image: Shindana's Little Friends collection represent children from around the world. A scan from the Shindana catalog | Courtesy of Billie Green