The Enduring Power of Modesta Avila, Feminist Icon and Orange County's First Convicted Felon

Sarah Rafael García first learned about Modesta Avila from a story in the OC Weekly. But she didn't fully appreciate Orange County's 19th-century feminist icon and first convicted felon until she started working on the project, "SanTana's Fairytales."

"I wanted to take some of the regional history and embed it into these fairytales to promote people to pay attention to history and how it relates to now," García said.

Modesta Avila stepped into California history one summer day in 1889 just before a Central California Railroad train came rumbling by her home. The 22-year-old walked the short distance to the tracks and placed "a heavy fence post" across them along with a sign that read, "'This land belongs to me. And if the railroad wants to run here, they will have to pay me $10,000,'" Historian Lisbeth Haas wrote in "Modesta Avila vs. the Railroad and Other Stories about Conquest, Resistance, and Village Life."

This land belongs to me. And if the railroad wants to run here, they will have to pay me $10,000.Modesta Avila

The train didn't crash that day in 1889 and no one was injured yet Avila was sentenced to three years in San Quentin Prison. Folklore has it that she died in prison.

Still, her legacy lives on. In the California State Railroad Museum's digital exhibit "Crossing the Lines: Women of the American Railroad," Avila is included because she "challenged the powers she believed were intruding upon her heritage and her community."

Avila wasn't the first and definitely not the last Latino, Indigenous or Black Californian to find themselves fighting for their home against the U.S. government or a giant corporation. From Santa Monicato Boyle Heights, entire communities have been ripped apart to make way for freeways or, in the case of Chavez Ravine, a commercial development.

Avila was born in California, 17 years into its statehood and during a time of great transition. Her parents were Mexican, Spanish-speaking Californios — Mexican and Spanish settlers of Alta California who were given land grants. Once the area became part of the United States, it became harder and harder for Californios to keep their land.

"There were a number of ways Californios could lose their property," Cal State LA Lecturer Donna Schuele explained.

One way was through legal fees associated with proving land ownership. Payment had to be made in cash, but before statehood, Californios did business on a barter system. When a ranchero needed cash, he would sell cattle or a piece of land. If he needed to borrow money, exorbitant interest rates were tacked on, she said.

Transactions weren't the only difference. Mexican law encouraged families to keep their ranchos together, Schuele said. If the ranchero died, his wife inherited the property. Upon her death, the children owned it together and could not sell their land without the other siblings.

"White settlers to California see something that's evil. They see land that is not being used, they see the land as essentially being hoarded," Schuele said. "So they're going to do everything they can, and they believe they have the moral high ground, in breaking up these ranchos."

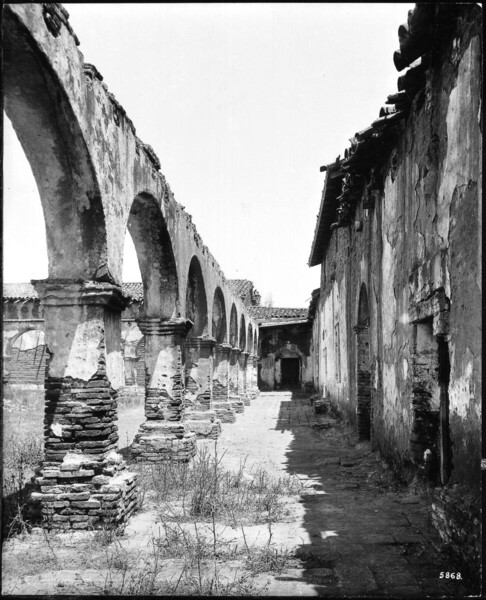

In Avila's case, she lived on a couple of acres in San Juan Capistrano in a house near her parents and her siblings. Unbeknownst to her, her parents sold their land before she laid claim to it against the railroad.

Whether or not she owned the land is not important to Avila's story, said García who was awarded a 2020 USLDH Mellon-Funded Grant for her project "Modesta Avila: Obstructing Development Since 1889 (#MAOD)", which creates a bilingual digital platform to tell Latinx stories.

Avila, who could read, write and speak English as well as Spanish, wasn't just fighting for her home and rights, but her family's as well.

"As children of immigrants of Spanish speaking households, the first English speaker of the household is still having to navigate this world," García said. "That means countering the justice system, that means countering the patriarchy, that means learning land rights and losing homes. To me, that is what's important about her."

On that day in 1889, Avila doubled down when confronted by postmaster Max Mendelson who scolded her for almost causing an accident. He had rushed to clear the tracks before the train came, having "overheard two boys say they anticipated a crash." She said to him, "If they pay me for my land, they can go by," according to Haas' article.

And she was so confident she would get what was hers, she threw a dance party at her home to celebrate her impending windfall. The next day she was arrested.

All these years later, people respond to Avila because she was a rebel, Haas said. She wouldn't be intimidated by the railroad and she rebelled against social norms at the time.

"She's such an outsider and yet willing to act as an insider as a person with rights," Haas said.

Those rights were permanently taken away after her first trial ended in a hung jury. At her second trial, Avila's virtue and character were also being judged by the all male jury (women weren't given the right to serve on a jury until 1946 in California and 1975 nationwide).

She's such an outsider and yet willing to act as an insider as a person with rights.Lisbeth Haas, historian and author of "Modesta Avila vs. the Railroad and Other Stories about Conquest, Resistance, and Village Life"

Avila was an unmarried Mexican American woman who had a boyfriend. Witnesses testified during her second trial that they saw her going into her house with men or going into other men's houses. One witness said he saw her drinking and a rumor was going around that she was pregnant.

Orange County had just become a county when Avila was convicted of obstructing the railroad tracks, which made her its first convicted felon. That along with the belief that she died in prison add to her mythos. In Historian Richard Brock's article "Modesta Again: Setting the Record Straight," he argues that she didn't die in prison and A Los Angeles Herald article dated July 29, 1893 said of Avila, "Her time is now finished and she is living in the northern part of the state enjoying freedom."

No matter what happened to Avila, she still exists in our culture as a symbol of resistance against the rich and powerful. In her now infamous mug shot, she looks straight at the camera, her eyes boring through history into you. You can see it on t-shirts, in books and public art and, if you believe, in the form of a ghost that haunts San Juan Capistrano.

García, who also founded LibroMobile bookstore, created an annual Modesta Avila award so activists, artists and writers could be awarded for their good work in the community as they are doing it — before they become legends.

"I always tell people, why do we have to be dead to be acknowledged? We should be acknowledging people now in the process of doing their work rather than, like Modesta, a hundred years from now when we realize, 'Oh, maybe she was on to something,'" Garcia said. "Because if we pay attention now we can actually do some preventive work instead of trying to fix the problems that have existed for over a century."