Manhattan Beach: The City Built on Sand Dunes Celebrates Its Centennial

This month, Manhattan Beach celebrates its centennial. Known for its lively seaside promenade, the Strand, and for its associations with surf culture, the city has its origins as a coastal resort built atop shifting sand dunes of the South Bay.

Though 2012 marks 100 years since Manhattan Beach's municipal incorporation, the city's history stretches back thousands of years. For millennia, foragers from the nearby Tongva village of Chowig-na passed through present-day Manhattan Beach, searching for shellfish and other food supplies. After the arrival of Europeans, the area became home to the large cattle and sheep ranches of Mexican California. The 1888 arrival of the Santa Fe Railway -- engineered by the Redondo Land Company, which owned much of the land in the area -- provided a reliable transportation link between the South Bay shore and the booming city of Los Angeles.

Some of the railroad's first passengers were entrepreneurs who envisioned a community, as well as fortunes, built atop the coastal sand dunes. One group of early investors from Pasadena organized in 1897 as the Potencia Townsite Company with the intention of creating a seaside resort. The development's name, Potencia, reflected the founders' enthusiasm for an early hydroelectric plant that briefly -- and unreliably -- harnessed the power of crashing waves to light a seaside boardwalk.

Manhattan Beach might today still be named Potencia were it not for John Merrill, another Pasadena developer who bought out the Potencia investors in 1901 and renamed the settlement after his hometown of Manhattan. Merrill laid out the original Manhattan Beach townsite, a 33-block beachside parcel between First St. and Center St. (since renamed Manhattan Beach Blvd.). To the north, Frank Daugherty developed a tract that he named Highland Beach, and another developer named George Peck founded what is today known as the North End section of Manhattan Beach. Although fertile soil could be found 1,000 to 2,000 feet inland, much of the town's new street grid encompassed a system of drifting sand dunes.

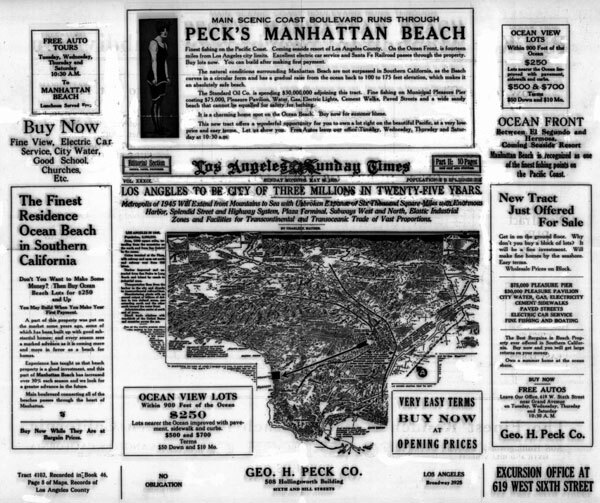

To sell the sandy lots, the developers promoted Manhattan Beach to the rest of the region as a forward-thinking investment, touting projections of regional growth and organizing excursion trains on the Santa Fe Railroad for prospective buyers. Beginning in 1903, curious Southern Californians could also reach Manhattan Beach on the Los Angeles Pacific Railroad, an electric interurban line that ran hourly cars to Manhattan Beach. (It later became part of the Pacific Electric Railway.)

Envisioned as a family-friendly resort town, Manhattan Beach's founders instituted strict rules about everything from women's bathing suits to alcohol consumption. Saloons were banned, with deed restrictions preventing the sale of intoxicating liquors.

Deed restrictions also prevented ethnic minorities from moving to Manhattan Beach, except for a two-block beachside tract that developer George Peck specifically set aside for people of color. In 1912, Charles and Willa Bruce became the first African Americans to buy land in the area. The neighborhood came to be known as Bruces' Beach after the Bruces built a two-story resort, complete with a dance hall and fishing pier, that functioned as a rare place where people of color could enjoy the Southern California shoreline. But racial hostility eventually claimed Bruces' Beach; as property values rose in the early 1920s, Ku Klux Klan gangs turned their intimidation tactics on the neighborhood. When they failed to dislodge the Bruces and other residents of the neighborhood, the city -- claiming it planned to build a public park there -- used its power of eminent domain in 1924 to seize the land and evict the Bruces.

Although proximity to the coast provided some consolation, Manhattan Beach's early settlers endured many privations. Most houses were simple wooden cottages. In its first few years, the town lacked streets and sidewalks, and there was neither gas, nor -- apart from the short-lived hydroelectric plant -- electricity. Writing in 1962, one early resident remembered life in Manhattan Beach in 1904: "Coal oil lamps and wood or gasoline stoves were used. Plenty of driftwood was available along the beach from the lumber boats that tied up at the Redondo wharves, for use in our wood ranges."

But by far the settlers' greatest challenge was the sand. Built on a system of sand dunes that stood as high as 60 feet and extended down from present-day El Segundo, the town struggled with the fine-grained sand that constantly drifted across streets, railroads, and boardwalks. Created by the prevailing onshore winds, the dunes ignored artificial constructions of the landscape, reappearing in alleyways and athwart thoroughfares. Residents planted ice plant to keep the shifting sands in place.

Eventually, during the 1920s, the Kuhn Brothers Construction Company found a solution: it began leveling dunes and transporting the sand to where it might be more useful. South Bay sand was used in construction projects from Los Angeles to Arizona, and barge-loads of Manhattan Beach's greatest nuisance helped replenish Waikiki Beach, the Oahu tourist destination plagued by an eroding shoreline. Manhattan Beach rid itself of many of its dunes in this way, although remnants remain, including a 100-foot-high dune where public access is controversially restricted.

North of Manhattan Beach, the sand dunes were put to good use. In 1911, the Standard Oil Company opened an oil refinery in El Segundo (the city's name refers to the fact that the refinery was the company's second in California) and placed its tanks atop the dunes so that oil could flow down to the tankers anchored offshore.

Standard Oil's decision to locate its facilities just a few miles north transformed Manhattan Beach from a summer resort into a potential home for refinery workers, and the town's population began to grow. In 1912, at developer George Peck's urging, the town of roughly 600 residents agreed to consider becoming an independent city. On November 25, 1912, Manhattan Beach voters went to the polls, and by a vote of 95 to 32, residents opted for cityhood, which became official on December 7.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, cultural institutions, and private collectors. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, and find Nathan Masters on Twitter and Google+.