Lost LA Field Notes: Venice

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

As we were making this episode, our production team often tripped up when referring to Abbot Kinney. We always had to clarify which Abbot Kinney we meant. Was it the man Abbot Kinney (born in 1850, and died in 1920)? Or was it the boulevard (previously named West Washington Boulevard until 1990)?

This tension between past and present, signifier and signified, is typical of Venice, California. Indeed, it’s telling that a bustling shopping street that seems so au courant today bears the name of a man who’s been dead for nearly a century.

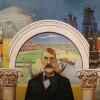

The neighborhood has been in a state of perpetual renaissance — always changing, always innovating, seemingly always reinventing itself — since tobacco heir Abbot Kinney founded Venice of America in 1905. And yet traces of the past, of Venices come and gone, stubbornly persist in street names, artworks and the built environment. We couldn’t resist exploring that tension between past and present in this installment of “Lost LA.”

A “Touch of Evil” Mashup

This episode includes what might be my favorite two minutes of “Lost LA” — a mashup of a classic film noir and a poetry reading.

Any student of cinema will immediately recognize the visual of the magnificent opening tracking shot from Orson Welles’ 1958 film “Touch of Evil.” The camera follows actors Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh through a dark and foreboding Venice Beach, thinly disguised as a Mexican-American border town.

Unlike the visual, the audio might escape immediate recognition.

When associate producer Katie Noonan and I came across Beat poet Lawrence Lipton’s “Bruno in Venice West” in the course of our research, we knew we had to use it in this episode. Not only because of its content but because the USC Libraries’ Special Collections could provide us access to Lipton’s handwritten manuscript of the poem, a typescript and an audio recording of him reading it. The poem was recently digitized with support from Council on Library and Information Resources’ Recordings at Risk program.

In the poem, Lipton imagines Giordano Bruno, who was a Renaissance-era mathematician persecuted by the Inquisition in Venice, Italy, for his heretical teachings, as he visits 20th-century Venice, California. As we began asking questions, experts cautioned us that they considered the poem one of Lipton’s lesser works. Nevertheless, we were drawn to the vivid imagery linking Renaissance Italy with the place Abbot Kinney intended as a beachhead for an American renaissance. Furthermore, we realized Lipton must have written the poem around the same time Welles shot “Touch of Evil.” In other words, the Venice West that Bruno encounters in Lipton’s poem is the same Venice we see Heston and Leigh strolling through:

"Up Main street, pausing to erect

the great crucifix in the Circle

before the U.S. Post Office, turning

into Windward avenue to St. Marks Hotel...

drunks and tarts

lurching along under the colonnades

like any Saturday night, the P.A. horns

blasting rock 'n' roll..."

Hence, the mashup, perfectly executed in the episode by editor Matthew Crotty.

Walking the Canals

Next time you’re in the neighborhood, bring this map along (pictured at the top of these field notes, and part of the Los Angeles Public Library’s Map Collection) and explore the original canals of Venice of America. Just don’t be surprised when a car horn interrupts your perambulations, because the canals that once were are now filled in, paved over and have been converted into city streets since 1929.

The canals that survive today, which were initially named the Short Line Canals after the Venice Short Line streetcar, were dug out after the originals and were not part of Abbot Kinney’s original plan.

The Archives

As I mentioned above, the USC Libraries’ Lawrence Lipton papers play a big role in this episode. So, too, does the archive of photographer Charles Brittin at the Getty Research Institute. Brittin trained his camera on Venice in the 1950s and 1960s, capturing the emerging Beat poetry scene and the historical African-American enclave of Oakwood.

Top Image: Abbot Kinney's original plan for Venice of America | Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Map Collection