A Walk Along L.A.'s Original Borders Reveals Surprising Remnants from the City's Past

To walk the border of the sprawling City of Los Angeles as it is today (about 503 square miles) seems an inconceivable feat for most. But what if that walk circumnavigated the city as it was in 1781 or 1850, when Los Angeles was square-shaped measuring four square leagues? In 2019, pedestrian advocacy organization Los Angeles Walks started a series of four walks — titled #LA4Corners — that retraced each of the four borders of the city when it was a young pueblo. The walk totaled approximately 26 miles. Each leg averaged six to eight miles, though freeways, hillsides, housing tracts and industrial sites made it impossible to walk the route in a direct line. While organizers facilitated conversations about street design as it related to pedestrian safety, presenters (and participants) shared enough local history to fill a book. These are just a few historical highlights from the #LA4Corner walks that began and ended at the plaques at each of the original four corners, placed by the Los Angeles Historical Society (LACHS) between 1978 and 1983.

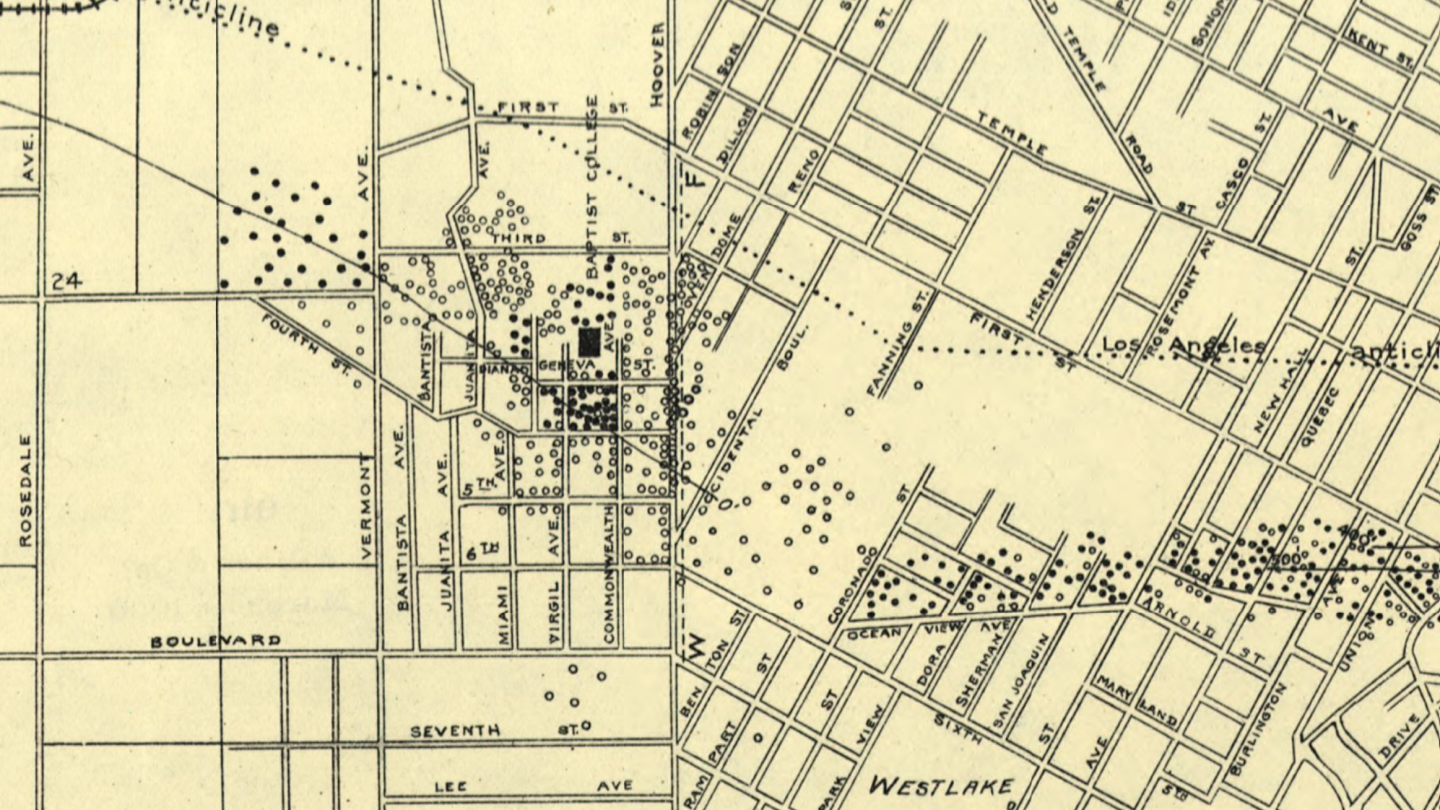

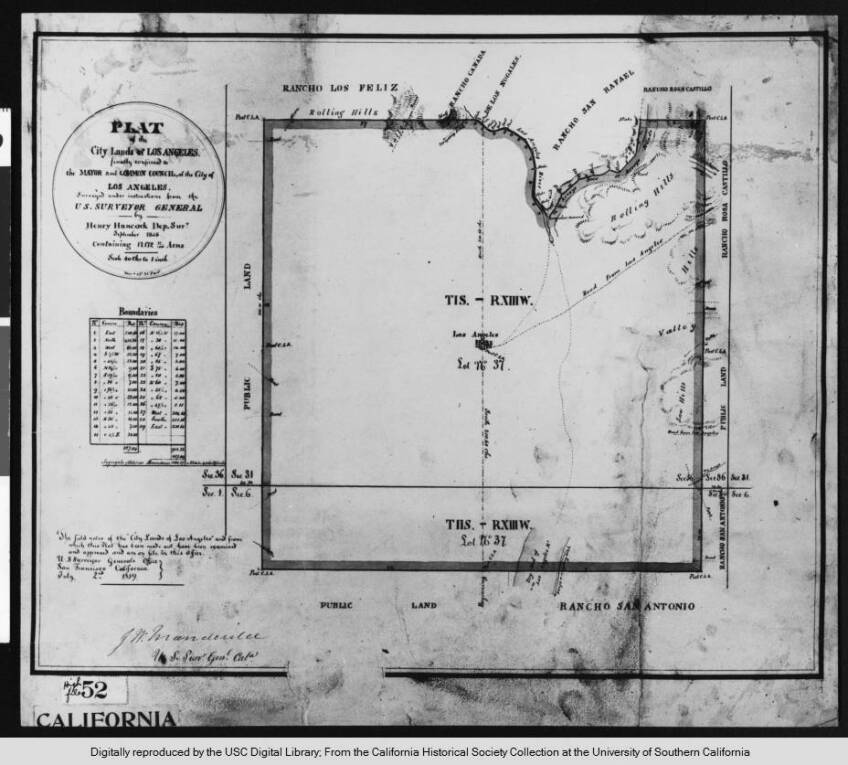

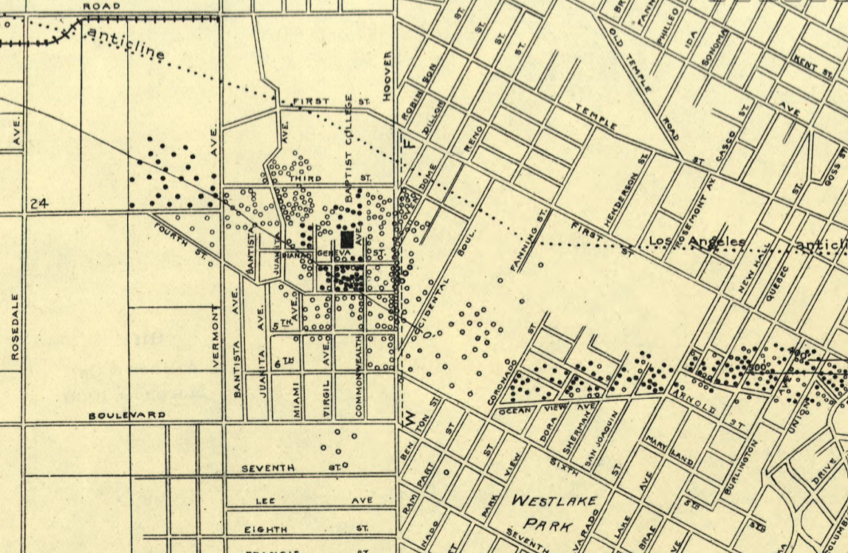

When Governor Felipe de Neve established Los Angeles as a Spanish pueblo in 1781, he drew upon the Law of the Indies, a series of proclamations developed in the 16th century that provided guidelines for new Spanish colonies. The new pueblo was laid over an existing network of Tongva villages that had developed over thousands of years. Spanish officials "drew Los Angeles into existence not on a blank canvas but instead upon a complex social and spatial landscape that bore the scars and cleavages, both deep and shallow, of historical and contemporaneous Indigenous-colonial exchanges," according to historian David Torres-Rouff in his book "Before L.A." The Law of Indies required that Spanish colonies be built near Indigenous villages for labor and located 20 miles from the ocean, near a fresh water source. Street grids were to be built at a 45-degree angle off the cardinal directions. Though in the book "Los Angeles Maps," D.J. Waldie explained, "The non-existent streets of the not-yet-city in 1781, as drawn by Governor Felipe de Neve, were cocked an imprecise 36 degrees."

While no formal survey exists from the Spanish and Mexican period, a diseño published in "Four Square Leagues: Los Angeles Two Hundred Years Later" shows the square-shaped pueblo surrounded by several ranchos. Diseños were hand-drawn sketches that defined property ownership in California, oftentimes relying on natural landmarks to indicate boundaries. When LACHS started setting the plaques at the original four corners in the late 1970s, the organization referenced Henry Hancock's 1858 survey of the city lands. As development grew beyond the city's original boundary, later surveyors used the Jeffersonian grid as mandated by the Public Land Survey System, causing a clash of street grids in Los Angeles.

Western Border: Walking through Hoover Street

A walk of Los Angeles's original four corners begins at the city's original northwest corner, which is now a busy five-point intersection at Fountain Avenue, Hoover Street and Sunset Boulevard. When the pueblo was founded, this area was probably dotted with a few well-worn roads leading to a nearby Tongva village, which was eventually swallowed up by Rancho Los Feliz by 1795. One hundred years later, pedestrians near this corner would've watched as Red Cars on the Hollywood Line rolled through Sunset Boulevard. While there is little trace of that history on the streetscape, there is a plaque about 500 feet away from the original northwest corner, just outside the Sunset Boulevard gate of what used to be KCET studios. In fact, the LACHS co-hosted the 1979 dedication ceremony with KCET because the studio had been designated as a Historic-Cultural Landmark the year before.

Today, the original western border follows Hoover Street through Silver Lake, Westlake and Pico-Union, but when it was surveyed in 1858 the land was mostly unoccupied. Hoover Street was named for Swiss doctor Dr. Leonce Hoover, a military surgeon in Napoleon's army who moved to Los Angeles in the 1840s. He and his son Vincent played prominent roles in the city's early civic history.

By the late 1800s, Victorian cottages and Craftsman bungalows weren't the only structures popping up along Hoover. Oil wells sprang up throughout Westlake as part of the Los Angeles City Oil Field that stretched from Vermont to Elysian Park. While not all struck it big, an Uncle Sam Oil Company well gushed in 1899 on Hoover, just north of 6th street. A few years before, the widow of the once-owner of Catalina Island, Clara Shatto, donated her property on the southwest edge of the oil field to the city with the condition it be a park. Despite warnings from self-serving oil speculators that the land was too saturated with oil to operate as public space, Sunset Park was dedicated in 1899. Now Lafayette Park, this is the site of the historic Felipe De Neve Branch Library (built in 1929) and "Hope at Lafayette," a new homeless shelter made out of refurbished shipping containers.

One clear indication that Hoover once served as the city's western border is how streets east of Hoover intersect with the streets west of Hoover. Since the Law of the Indies required streets to be cocked at an angle from the cardinal directions, most streets within Los Angeles' original border intersect with Hoover at the diagonal compared to those west of Hoover established with the orthogonal system. This created a number of triangular and odd-shaped blocks east of the street. One historic landmark built to fit its uniquely shaped site was the First Church of Christ, Scientist at Hoover and Alvarado. Architect Elmer Grey designed this Italian Romanesque church in 1912, which is now the Central Spanish Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Pico Union. Across the street, a 1901 Queen Anne home featured in an early edition of "An Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles" still stands.

Further down Hoover at 24th Street is the Velaslavasay Panorama housed in the old Union Theater, once used as a union hall. During the walk, the Shengjing Panorama was on display, a 360-degree painting of the Chinese city of Shenyang between 1910 and 1930. To "transport" Angelenos to the Chinese city, the exhibit featured a miniature version of L.A.’s now-gone La Grande Station, an 1893 ornate Moorish-style depot for the Santa Fe Railroad. The theater falls in the historic University Park district full of Victorian homes, such as the Cockins House and the Salisbury House. Still standing at Hoover and Adams is the Sunshine Mission for Women, originally the Froebel Institute designed by Myron Hunt in the Mission Revival style in 1893. The campus transformed into a school for young women called Casa De Rosas in the early 1900s and now the site is currently undergoing much-needed repairs to help house those experiencing homelessness.

![Casa de Rosas campus (circa 1897) in Los Angeles. This view of ivy and rose-covered house on Adams Street; shows gables with flared eaves on Mission Revival style building, dormer (left), chimneys, porte cochere. Partially covered word "[Froebel] Institute" above entrance arch (right).](https://kcet.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/520cdc3/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6252x3947+0+0/resize/848x535!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkcet-brightspot.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Ff0%2Ffc%2Fbff2f7f9439a8c6334472ff670bc%2Ffl212078-casa-de-roses.jpg)

![Casa de Rosas campus (circa 1897) in Los Angeles. This view of ivy and rose-covered house on Adams Street; shows gables with flared eaves on Mission Revival style building, dormer (left), chimneys, porte cochere. Partially covered word "[Froebel] Institute" above entrance arch (right).](https://kcet.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/87a7a23/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6252x3947+0+0/resize/1920x1212!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkcet-brightspot.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Ff0%2Ffc%2Fbff2f7f9439a8c6334472ff670bc%2Ffl212078-casa-de-roses.jpg)

While the southwestern corner plaque at Exposition and Figueroa is missing (lost during the construction of the Expo Line), the western border walk finished at the 1927 Rose Garden in Exposition Park, a scenic end to the walk down Hoover. Referring to the clash of street grids very evident on Hoover, #LA4Corners participant Michael Massman said at the end of the walk, "What was really amazing to me was to see the actual intersection between the old Spanish town of Los Angeles compared to its more modern American part. Walking along Hoover, you could see that really dramatically."

Southern Border: An Unexpected End Point

Unlike the western border, no one street clearly delineated the city's original southern border. This walk follows a zigzag path that starts at the corner of Exposition Boulevard and Figueroa Street and winds through residential and industrial streets of historic South Central. These neighborhoods were "some of the first sections of the city to be subdivided during the late 1880s land boom … some of the few remaining examples of the city's earliest residential suburban development, many of which were constructed in the Queen Anne-style," according to SurveyLA. Though not exactly on the route, landmarks like Paul Williams' 28th Street YMCA and the Sears Building are visible enough to elicit oohs and ahhs from walkers.

Old railroad tracks peeking through the asphalt at Broadway Place near 35th Street are not the only noticeable reminders that the Southern Pacific Railroad once defined this segment of the city's southern border. The trains are gone but the railroad's right of way and the oddly shaped buildings are a clear indication of where part of the southern border was once located.

The route crosses over the historic Central Avenue, dubbed the "the Black belt of the city" by the California Eagle. The city's racial covenants prevented African Americans from owning land in certain parts of the city, which forced them into neighborhoods like those around Central Avenue. According to Historian Steve Isoardi, "By 1940, approximately 70% of the Black population of Los Angeles was confined to the Central Avenue corridor." On the #LA4Corners walk, a stop was made at the historic 27th Street District Bakery. Jeanette Bolden-Pickens, third-generation owner of the 27th Street Bakery, took a few moments to share a few family stories about the bakery first opened by her grandparents in 1956.

Once past the residential neighborhoods, the walk wanders through an industrial section full of old warehouses, a few turned into art spaces. On a mostly tree-less walk along Washington Boulevard, east of Alameda, pedestrians pass under one of the last steel truss bridges in City of Los Angeles before walking over the Los Angeles River along the Washington Boulevard Bridge. Built in 1931, this bridge features bas relief sculptures that depict engineers in the act of building a bridge.

The walk ends at the busy intersection of Olympic and Indiana where the southeast corner plaque is located behind the gate of a smog check shop. Heads nodded as #LA4Corner walker Joni Yung remarked, "You don't even know that plaque is here unless someone pointed out."

Eastern Border: Between City and County

A walk along the original eastern border starts at Debs Park in Northeast L.A. and ends in East L.A. at the corner of Olympic and Indiana Streets. Of all the original four borders, Indiana is the only street that still functions as the border between city and county. The northeast plaque is located at the Debs Park entrance, although to avoid extra hills, the walk actually started on the appropriately named Boundary Avenue in Rose Hills Park.

After walking down the hill from Rose Hill Park, the route heads west down Huntington Drive until it meets Soto Street and Mission Street. This was the site of the recently demolished Soto Street Bridge in El Sereno that carried Pacific Electric cars between downtown and Pasadena. Now, steel butterflies created by artist Michael Amescua fly over a pocket park that displays a piece of the original bridge. When ambling south along Soto Street, one sees the Forever 21 warehouses where the Selig Zoo once operated. On the other side is Ascot Hills Park, the former site of the Legion Ascot Speedway between 1924 and 1936 that is now full of hillside trails with photographic views of the downtown skyline.

Walking the city's eastern border requires crossing the San Bernardino Freeway and El Monte Busway (through a fenced-in pedestrian bridge) and under the Pomona and Santa Ana Freeways. In his book "Folklore of the Freeway," Eric Avila explains how "six freeways bullied their way into Boyle Heights, converging on two massive highway interchanges that consumed 10% of the local housing stock." Each leg of this series of walks requires walking over or under freeways and illustrates how neighborhoods were separated and/or destroyed when building this massive infrastructure.

Perched atop Indiana Street at Folsom is the majestic El Pino, a pine tree landmark made famous in the film "Blood In, Blood Out" that is one of the few landmarks at the border of city and county seen from miles away.

Like Hoover, Indiana Street clearly illustrates the clash between the Spanish and American street grids with oddly angled streets along the west side of Indiana. In fact, this is what created the well-known five-point intersection Los Cinco Puntos at Indiana Street, Cesar Chavez Boulevard and Lorena Street, where the first Chicano Moratorium march began in 1969. The beloved Los 5 Puntos deli opened at this intersection in 1967. Across the street in the triangular-shaped park, local veterans stand guard every Memorial Day during a 24-hour vigil at the Mexican American All Wars Memorial.

Indiana skirts the corner of the historic Evergreen Cemetery established in 1877. The cemetery is home to a number of pioneering families with recognizable names like Mason, Hollenbeck, Lankershim and Van Nuys. Further down Indiana, a quick detour can be made to Salazar Park (originally Laguna Park), the site of the 1970 Chicano Moratorium rally that erupted in chaos when "Los Angeles County Sheriffs brutally disbanded the gathering," according to urban planner James Rojas. Paul Botello's 2001 mural "The Wall That Speaks, Sings, and Shouts" on the park's recreation center features a portrait of Ruben Salazar, the Mexican American journalist killed by a sheriff's tear gas canister that day. The walk ends at southeast corner, back at the smog check shop where it has stood for the last 30 years.

Northern Border: The Final Challenge

The northern border walk was the longest and most arduous. Like the southern leg, it's difficult to walk this border in a direct route as it requires scaling hillsides and intimidating stairways while navigating around the Los Angeles River. This walk started in Sycamore Park and stopped at the historic Charles Lummis House, appropriate for Los Angeles Walks since Lummis famously arrived to Los Angeles in 1885 after walking from Cincinnati.

From the Lummis House, the walk follows down Highland Park's Figueroa Avenue toward the Riverside Bridge. At the bridge, standing in the first roundabout in Los Angeles, is the public art sculpture "Faces of Elysian Valley" inspired by residents from the neighborhood. The Riverside Bridge sidewalk spills out into the pedestrian path along the Los Angeles River, which provides a peaceful respite from the car traffic. This section of the river path skirts along Frogtown, named after the tiny frogs that often overwhelmed the neighborhood between the 1930s and 1970s. These frogs (which were more likely Western Toads) would emerge from the river after the rainy season and hop through the neighborhood streets and front yards.

After walking alongside the river, the trek then enters the hills of Elysian Park, Echo Park and Silver Lake, and what was considered Edendale in the early 1900s. The hillside community was also given the moniker "Red Hill" for the socialists who lived tucked away in the hillside bungalows. A number of stairways punctuate this part of this route, including the historic Mattachine Steps that commemorate the Mattachine Society and its founder Harry Hay, who organized one of the first gay rights groups in the country. This long hilly walk ended where the first #LA4Corners walk began, near the intersection at Fountain and Sunset.

For many on the #LA4Corners walk, completing a trek around the original boundary of the City of Los Angeles led to a deeper understanding of the city before cars dominated the landscape. Experiencing the two different street grids — the Spanish and American — by walking each border helped to peel away the layers of history that have been paved over, and sometimes erased, by the built environment. There are a number of reasons to walk the city's original border and one of them was best expressed by Los Angeles Walk staffer Daisy Villafuerte: "I hope that people really understand that a lot of these neighborhoods that sometimes we just pass through are not just places that we should just pass through. But are places that people have rooted into…and hopefully [this will] build a greater understanding and connection with people who live in these communities."

Author’s note:

In 2019, Los Angeles Walks organized the #LA4Corner series based upon a walk developed by Daveed Kapoor, Lila Higgins, Nathan Masters and Victoria Bernal which could not have been done without the input from a number of local historians. The history documented above represents only a small percentage of all the stories shared by the many storytellers and participants who joined in the walks.

To encourage walking during the pandemic, Los Angeles Walks created these "turn lists" for the north leg, the south leg, the east leg and the west leg for those interested in walking the original border on their own. While Los Angeles public space is for everyone, please be respectful if walking as a stranger or resident through these neighborhoods.