Los Angeles in Buildings: The Ambassador Hotel

“Last Tuesday night, for the first time in 30 years, I found myself by one casual chance in a thousand on hand, in a small narrow serving pantry of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles,” said a pained Alistair Cooke on his “Letter from America” broadcast of June 9th, 1968. He then vividly described that onetime playground of silver-screen royalty (and, from time to time, actual royalty) as “a place that I suppose will never be wiped out of my memory as a sinister alley, a roman circus run amok, and a charnel house” — the site, in other words, of the assassination of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, five years after the similarly shocking murder of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, moments after his victory in California’s Democratic primary election.

The bullet fired by young Palestinian radical Sirhan Sirhan ultimately killed not just Robert F. Kennedy but the Ambassador Hotel itself.

Though it temporarily elevated that pantry into the canon of sacred American spaces, the bullet fired by young Palestinian radical Sirhan Sirhan ultimately killed not just Kennedy but the Ambassador Hotel itself. Already well past its glory days by the late 1960s, its decline hastened sharply thereafter until its demolition in 2005, sixteen years after its last guests checked out. Half a decade after that, the new complex of buildings newly risen on the Ambassador's site opened its doors: the pharaonically expensive Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools, not just an educational facility, and not just a tribute to the slain dynastic politician, but a symbol of Los Angeles' difficult search for coherence in both its architectural identity and its attitude toward the past.

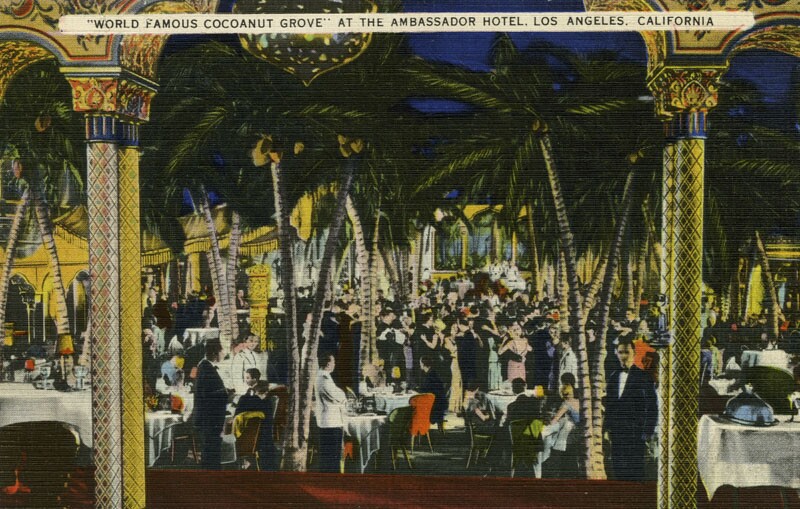

Many still mourn the Ambassador, but who mourns the dairy farm the Ambassador itself displaced? When its construction began in the early 1920s, then marveled at by the Los Angeles Times as “the most stupendous hotel project in the history of the United States,” Wilshire Boulevard was nothing but a dirt road. To some Angelenos back then, its site three miles from downtown might as well have been 300 miles from downtown. But after the Ambassador opened its doors on New Year's Day 1921, with its storied nightclub the Cocoanut Grove following a few months later, its presence (which one advertisement quoted pulp writer Gouverneur Morris describing as that of “a three-ring circus of indoor and outdoor amusements in a layout filled with happy conceptions”) helped turn Wilshire into the central economic artery of Los Angeles.

It surely helped that Cocoanut Grove attracted, among others, Rudolph Valentino (who, legend has it, brought in the club's signature papier-mâché palm trees from the set of his picture “The Sheik”), Charlie Chaplin, Joan Crawford, Errol Flynn, Jimmy Stewart, Lucille Ball, Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, and Katharine Hepburn – not to mention that it served alcohol during Prohibition. The passage through of not just cinematic legends but the likes of Howard Hughes, Charles Lindbergh, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald (who famously burned down one of its bungalows in a marital spat), Albert Einstein, the sequestered Charles Manson jury, and Nikita Khrushchev (who received a visit from Mickey Mouse at the hotel in lieu of a much-anticipated trip to Disneyland), as well as – so one often hears – six Academy Awards ceremonies and every U.S. president from Herbert Hoover to Richard Nixon, made the Ambassador a historic place deserving of protection.

Or some thought it did, anyway. Others considered the claim little more than the Los Angeles equivalent of “Washington slept here,” and made on behalf of an increasingly decrepit structure of scant architectural distinction at that. In a letter to the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission recommending against official landmark status for the Ambassador, Robert Winter, co-author with David Gebhard of “An Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles,” described it as “is in no way vital to the heritage of the city. The exterior never had any redeeming qualities, and its original mediocrity has been botched by hideous intrusions of a relatively recent vintage.” So much for the efforts of Myron Hunt, the architect also responsible for Pasadena's Rose Bowl and the Huntington Library, to, with a hybrid of Mediterranean Revival and Art Deco, capture and even define the spirit of a still-emerging Los Angeles.

So much, too, for the work of Paul Williams, the architect later commissioned to bring a bit of the jet age into this jazz-age building, most notably with its much-filmed midcentury modern coffee shop. The author of more than two thousand private homes in Los Angeles, some of them designed for the very members of high society who frequented the Cocoanut Grove in its heyday, Williams also held the distinction of being the first black member, and later fellow, of the American Institute of Architects. His contribution to the Ambassador also included a couple of new bungalows and a remodel of the Embassy Ballroom where Kennedy would give his final speech, but whether it all held up aesthetically in his oeuvre presumably mattered less to its protectors than the sociopolitical importance of its designer's career.

But when the decisive time came to defend the Ambassador and its history, history had already had its way with the Ambassador. Kennedy's shooting happened just as it became clear how much trouble American cities, bled by the loss of their taxpayers to the suburbs since the end of the Second World War, were really in. The rapid deterioration of the surrounding neighborhood, now known as Koreatown but once referred to, drawing on the hotel's reflected panache, as the “Ambassador District,” mirrored that of “inner-city” neighborhoods all over the country. A last-ditch 1970s modernization effort helmed by Sammy Davis Jr. installed shag carpeting and disco balls, rebranding the Cocoanut Grove, with a dank purple-and-yellow color scheme, as the “Now Grove,” but it may only have hastened the Ambassador's demise: the owners closed 350 of its 500 rooms in 1986, then closed all of them three years later.

True to its name, the Los Angeles Conservancy fought to keep the empty Ambassador standing, an effort its website describes as an “epic battle” but which, in other quarters, looked like an unrealistic one. The Conservancy's opponents included the Kennedy family, who favored an end to the Ambassador's grim afterlife as hallowed ground, but its final and strongest antagonist turned out to be the Los Angeles Unified School District. Playing the reliable “Won't somebody think of the children?” card, it identified the 24-acre site as a promising one for a new school to accommodate the many students of Koreatown then bussed out daily as far as the suburban San Fernando Valley.

Despite using next to none of the Ambassador's original parts, the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools pays clear homage – and in the eyes of some architectural critics, too clearly pays homage – to the old hotel.

Initially advocating for whichever school construction plan would retain as much of the Ambassador's structure as possible, the Conservancy eventually settled, after a blaze of litigation, for the preservation of the Cocoanut Grove alone, to be repurposed as an auditorium, and the establishment of a $4.9 million fund for the saving of other historic school buildings. In the event, very few elements of the renowned nightclub survived. “The LAUSD said they would work with us through a process,” Diane Keaton, actress-preservationist and Conservancy board member later said, “but it was a charade. They went through the motions, but they had no intention of saving the building.”

Despite using next to none of the Ambassador's original parts, the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools pays clear homage – and in the eyes of some architectural critics, too clearly pays homage – to the old hotel. “The overall design is not really rooted in anything except maybe the city's obsession with loosely recreating the past,” declared Sam Lubell in the Architect's Newspaper. “If anything it's a painful reminder of what was there before; an authentic piece of L.A. history that's been replaced by a loose nod to it.” Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne saw in it “the decisiveness neither to save the original hotel complex as a school nor to make a clean break with the past, … not just an attempt to make new look old but an odd mixture of progress and guilt” that “wraps both ham-handed reverence for history and naked disdain for it inside a single architectural package.”

This awkwardness wouldn't matter quite so much had it cost less than $578 million, making the project the most expensive public school in American history, though not the most expensive per seat: that dubious honor belongs to downtown's High School for the Visual and Performing Arts, another of the LAUSD's high-profile architectural compromises. And a good compromise, as we all know, leaves everybody mad, especially those who worry about the loss of Los Angeles' glamorous past, an obsession that can manifest as aggressive defense of automobile-era kitsch. “To witness the perils of piecemeal preservation, one need only look directly across the street from the Ambassador,” the Conservancy's then-director of preservation issues Ken Bernstein seethed in a 2003 op/ed, “where the once-famed Brown Derby restaurant hat now sits perched ridiculously and meaninglessly atop a two-story mini-mall.”

A transpacific parallel to the struggle for the soul of 3400 Wilshire erupted in 2015 over the redevelopment of the main wing of Tokyo's Hotel Okura. Opened across the street from the American embassy in 1962 in anticipation of the city's 1964 Summer Olympic Games, the Okura hosted (picking up, in a sense, where the Ambassador left off) every U.S. president from Richard Nixon through Barack Obama, the launch of the very first VHS recorder, and, in the novel “You Only Live Twice” as well as its film adaptation, no less a fictional personage than James Bond. But when Tokyo put in the winning bid for another Olympics, in 2020, the hotel's owners decided the time had come for a thorough overhaul of the hotel's East-meets-West, “Mad Men”-and-plum-blossoms modernism.

“The best bit of the most loved hotel in Tokyo will be torn down by its owners to make way for a 38-storey glass tower,” wrote Monocle's Fiona Wilson on savetheokura.com, a site the travel and culture magazine established in an attempt to do just that. “It will be a heartbreaking and irreparable loss.” Its visitors could “walk into the main building of the Hotel Okura today and still drink in the atmosphere of 1960s Tokyo,” surrounded by “displays of seasonal foliage, arranged by an Ikebana school,” attendants who “wear their kimonos with unselfconscious ease” as well as “staff in tuxedos and bow ties, a Japanese garden and a bar where they’ve been making highballs since they were fashionable the first time around.”

Other observers joined in Monocle's lament, albeit for the most part Western rather than Japanese ones. “When the reconstruction was announced, many foreigners, especially well-known designers, voiced their regret,” Toyo University architecture professor Yoshio Uchida told the New York Times. “The magnitude of their protest was beyond our imagination.” But the locals have a different attitude toward architecture and its preservation, seemingly secure in the knowledge that the culture can produce both economically and aesthetically valuable buildings in the early 21st century just as well as it could in the mid-20th – or indeed in the 8th, since which time the Ise Jingu grand shrine, perhaps the structure most emblematic of the Japanese way of building, has every 20 years been torn down and rebuilt on an adjacent plot.

A place like Los Angeles, by contrast, has a way of conflating the artifacts of a culture and the culture itself. The relatively venerable works or architecture that survive there, whatever their aesthetic achievement or lack thereof, have come to represent a time, dimly remembered if not simply imagined, when the city possessed more ambition, more refinement, more pizazz than it does today. If, as Los Angeles' preservationists assume, only bland, characterless developments can now take the place of every fallen Ambassador Hotel (or Brown Derby or Richfield Tower or Pan Pacific Auditorium), it isn't because the guardians of the city's history haven't risen to the responsibility of ensuring a sufficiently inspiring built environment; it's because the culture of the Los Angeles that gave rise to all those grand old buildings in the first place has died, as surely Robert F. Kennedy did that fateful night in 1968.

Even in Los Angeles' supposedly still ambitious, refined, and pizazz-filled mid-20th-century, the wrecking ball swung freely. The Ambassador first avoided it in 1957, when the office of Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall (the recently rediscovered retro-cool of whose American Cement Building has graced MacArthur Park since 1964) proposed a development called the Ambassador International. Entailing a complete teardown and rebuild of the hotel along with a few new high-rises to surround it, the project has a certain something in common with the new Okura, designed by the son of the old Okura's original architect with an eye toward not just retaining its use but reimagining its sensibility.

But the scale of the Ambassador International, quite large for the Los Angeles of those days, is nothing next to the scale of the development proposed immediately after the Ambassador closed down in 1989. Had it not been thwarted by the LAUSD's decision to take possession of the property by eminent domain, it would have filled the hotel's 23.5 acres with a complex of restaurants, movie theaters, “power retail” outlets, and, its gilded and diamond-patterned exterior rising to 125 luminous stories, the tallest tower in the world. The mastermind of this effort to erect a hypertrophic Rockefeller Center of the West Coast? A man who, having failed to make his mark on Los Angeles, would go on, like the senator gunned down on the Wilshire Boulevard real estate he so coveted, to act on presidential ambitions of his own: a certain Donald Trump. His vision for the Ambassador may have gone unrealized, but one can only imagine what Alistair Cooke would have had to say about the result of his campaign.