Lions and Tigers and Cameras! How the Movies Gave Los Angeles a Zoo

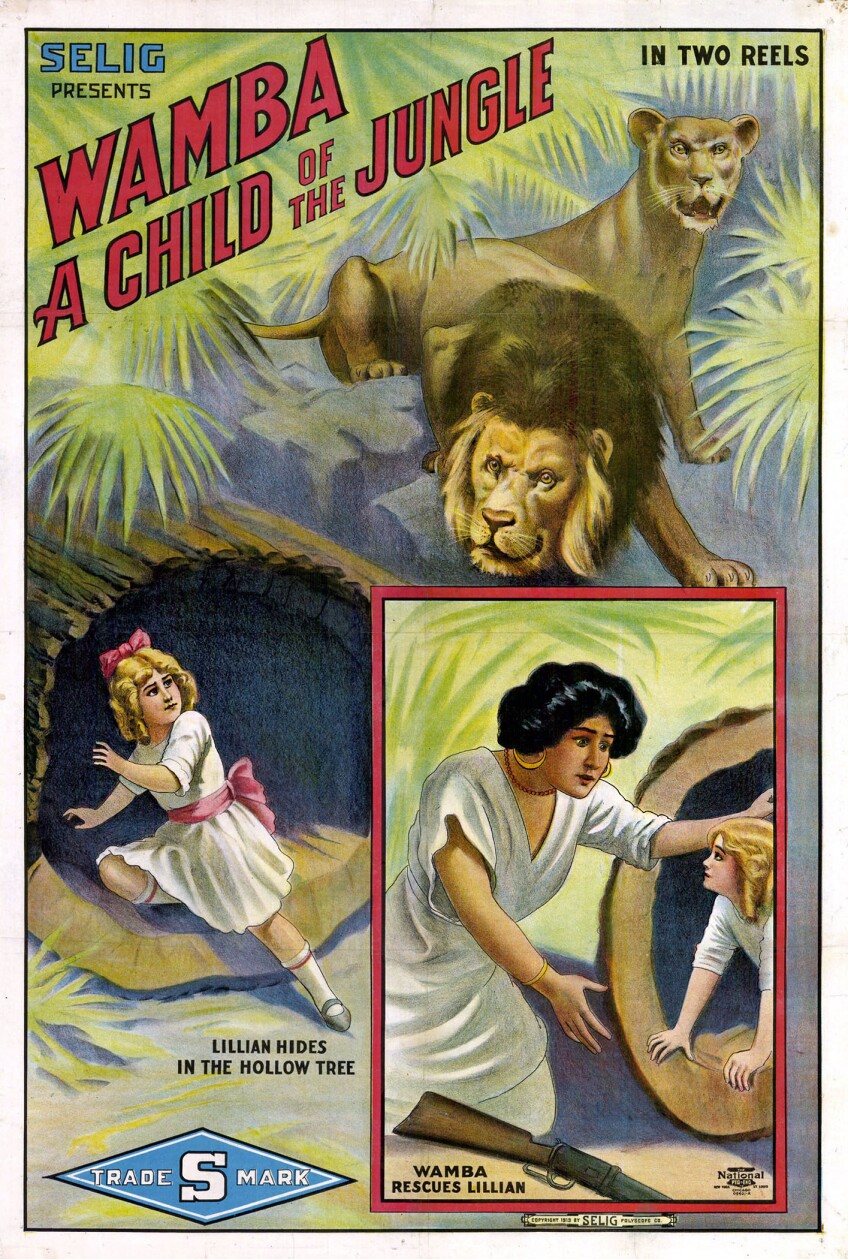

The shadows caught inside "Colonel" William Selig's Polyscope camera flickered across 2,000 feet of silent film in 1913 to tell the story of "Wamba, a Child of the Jungle," a 25-minute melodrama of "darkest Africa" shot around the Silver Lake Reservoir. Movies before World War I were made in New York, Chicago and Hollywood, but also, in Edendale (today's Los Feliz and Silver Lake), where Selig's menagerie of lions, leopards and elephants threatened heroines and mauled villains in the "jungle pictures" the Selig Polyscope Company made popular.

With bamboo props, paper ferns, actors in loincloths and a hut thatched with fronds from a fan palm, Selig made Edendale a barely believable simulation of the tropics. The animals, at least, were real. When they weren't appearing in a Selig movie, they were rented out to other film companies or performed for studio visitors.

Selig was successful, producing the first filmed version of "The Wizard of Oz" and movies based on classic novels like "The Count of Monte Cristo." In 1915, he opened a second, larger studio next to Eastlake Park (later Lincoln Park) in Lincoln Heights. Selig's collection of animals moved with the actors, sets and cameras.

Animal attractions were popular tourist destinations in turn-of-the-century Los Angeles. The Cawston Ostrich Farm (1886) in Pasadena was among the earliest. Selig's neighbors around Eastlake Park were the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm (1906) and the California Alligator Farm (1907). A tiny city zoo had occupied a corner of Eastlake Park until it moved in 1912 to new quarters in Griffith Park.

Selig's 35-acre site, with easy access by trolley and streetcar, created an opportunity — not for another animal farm but for a real zoo with elephants, tigers, lions, monkeys and hundreds of birds. And not just a zoo, but also a "pleasure garden" with a giant dance pavilion, roller skating rink and picnic grove with landscaped grounds large enough for 8,000 visitors. Film production at the rear of the park would go on, its jungle-like acres separated from the zoo by a security wall.

The Selig Zoo opened on June 20, 1915 with the arrival, said the Los Angeles Times, of "four elephants, two camels, two sacred cows [Brahman cows], ten tigers, ten leopards, seven lions, eight trick ponies, one boxing kangaroo and one trick mule. Fritz and Lena are the most valuable animals in the park. They are giraffes and are valued at $5,000 each."

The data-conscious Times calculated the cost of the zoo's daily menu for the zoo's collection:

Two hundred and fifty loaves of bread, two beeves, three bunches [of] bananas, fifty gallons milk, one wagon-load of vegetables, one ton of hay, twenty-five bushels of oats, two sacks of pheasant food and sacks of bran and delicacies for the more particular and fastidious birds and animals.

Visitors entered the zoo through a pair of monumental arches, each flanked by strangely emaciated lions, separated by a podium of bellowing elephants, molded in concrete to the designs of Italian sculptor Carlo Romanelli. "The entrance, presenting an artistic array of life-sized animals," said the Times, cost $75,000.

Living lions and tigers were caged under long arcades that surrounded a wide lawn. Birds were housed in an aviary. Monkeys had their own pavilion. Other animal displays simulated a rocky hillside. The giraffes had a very tall enclosure.

The Selig Zoo, with over 700 animals, was an immediate success. A picnic for department store clerks and their families attracted 5,000 visitors. Jewish Orphan Relief brought in 10,000 and raised enough money to pay off the mortgage on the Boyle Heights orphans' home. On Mexican Independence Day, under chairman C. C. Moreno, all the attractions of the zoo and park were free.

The zoo attracted 300,000 visitors a year to watch a daily animal show featuring "Leopard Lady" Olga Celeste and to gape at the monkeys, take elephant rides and stroll on meandering paths.

Beyond the park grounds and zoo, where filming went on, there were "runs for jungle scenes, caves for illusions, an exact duplicate of a village in Colón [Panama], and the large collection of structures known as Bloom Center" that could pass for a Western town or a New England village.

Perhaps Selig had dreamed too big or the movie audience had become more sophisticated or the new Hollywood studio system — integrating theater ownership with production — out performed independents like Polyscope or World War I dried up European film sales. By 1918, Selig's studio and the Selig Zoo were bankrupt. Louis B. Mayer rented the studio briefly. The zoo passed into a succession of owners through the 1920s into the late 1930s, always struggling to match gate receipts with the costs of displaying hundreds of animals.

Flooding in 1938 killed some of the exotic birds and damaged some of the zoo buildings. The lions and tigers tamed for film production were eventually sold to rental suppliers. Other animals were donated to the Los Angeles Zoo, which began its evolution into the zoo Los Angeles has today.

The early days of the movies in Los Angeles inadvertently allowed visitors to experience the largest collection of animals in the western United States. All that remains are a few of the cement lions, discovered in a wrecking yard in 2000, refurbished and brought to the Los Angeles Zoo in Griffith Park in 2009. Their fixed growls and glowering stares once thrilled children who walked beneath them at the Selig Zoo.

At the northern edge of Lincoln Park is a stub of a street — Selig Place — a nearly forgotten reminder of a pioneering entertainer and entrepreneur who gave Los Angeles a zoo.

Sources

Andrew Erish. "Col. William N. Selig: The Man Who Invented Hollywood." Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.