L.A. Was Once Home to the World's Largest Flock of Pigeons

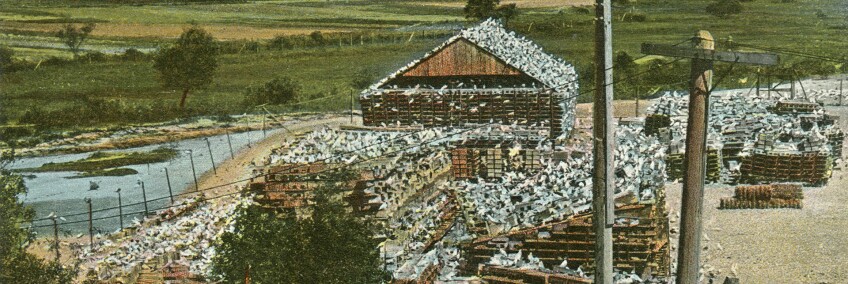

Pigeons: today the birds scavenge L.A. sidewalks and suffer unflattering nicknames like "winged rats," but in the early 20th century they were, improbably, one of the city's biggest tourist attractions. Until a flood destroyed it in 1914, a pigeon ranch on the Los Angeles River was home to the world's largest flock of the cooing birds, drawing thousands of curious onlookers eager to glimpse the spectacle.

Established in 1892, the pigeon ranch's primary purpose was not tourism but food production. Squab meat was then a luxury food item in the U.S., served at fine restaurants across the country. Though farmers had long kept pigeons in dovecotes as a ready source of food, demand always seemed to outstrip supply in the commercial squab market. The Los Angeles pigeon ranch was among the first attempts to raise the birds on an industrial scale, its coop-houses situated on eight acres of treacherous flood plain near the river's confluence with the Arroyo Seco.

The operation prospered under owner J. Y. Johnson, who purchased it in 1898. At its peak the ranch was home to more than 100,000 birds. As many as 4,000 went to market each month, fetching about 25 cents per head. Only the young, flightless squabs were killed for food; the older, flying birds were kept as breeders, each pair producing an average of twelve squabs per year. The ranch also sold the birds' guano and molted feathers as fertilizer. Rat traps protected the nests from predatory rodents, while chained dogs guarded the flock from human poachers.

Johnson discouraged sightseers, but the spectacle of thousands of white pigeons bobbing on the ground or huddling on the rooftops was irresistible. Visitors came to the banks or peered down from Elysian Park to see the birds. Picture postcards were made for the benefit of friends and relatives back home.

"A visit to this queer ranch is one of the pleasures enjoyed by most tourists," wrote the Washington Post correspondent, who described it as a "flourishing little town of pigeons."

The ranch attracted journalists from around the world, too. "A visit to this queer ranch is one of the pleasures enjoyed by most tourists," wrote a correspondent for the Washington Post, who described Johnson's ranch as a "flourishing little town of pigeons."

Writing for Pearson's Magazine of London, Ernest Rydall noted the sounds that emanated from the ranch's multiple coop-houses. "One of the strangest noises ever heard is the constant cooing from the throats of these thousands of pigeons. It reminds me of the winds blowing through old windows in winter, or the ceaseless dashing of waves upon the beach a long distance away."

Local commentators took the booster angle, attributing the ranch's success to the region's climate. "Southern California is particularly favorable to pigeons," Pasadena naturalist Charles Frederick Holder reported in Scientific American. "The perpetual summer is an important factor."

Bertha H. Smith echoed Holder in Sunset Magazine: "The raising of squabs for market is a ticklish business. More than one man has tried it and failed. The growth of this ranch, which started three years ago with a stock of two thousands birds, shows what pigeons think of California climate, and that is one of the secrets of its success."

Ironically, the region's climate proved to be the ranch's downfall. Most days may be warm and dry, but there is no "perpetual summer." When storms roll into Southern California's inland mountains, rainfall can be intense, transforming the region's normally tame watercourses into raging torrents. So when a particularly violent Pacific storm visited Los Angeles on February 21, 1914, Johnson's ranch – located on the flood plain, just above the river bed – was doomed. The swollen Los Angeles River tore through the ranch and carried the coop-houses toward the ocean. Popular Science Monthly described the aftermath: "Tens of thousands of birds were drowned. The few survivors hovered about their former home for weeks – some of them for months; but they could not be brought together as a family again, and finally they scattered."