L.A. vs. the Saloons, Part I: Regulating the "Hatcheries of Sin" and "Sinks of Iniquity"

In the last decades of the 19th century, stories of the city’s saloons and the evils of liquor filled Los Angeles’ newspapers. For Angelenos of the time, the “hatcheries of sin,” “sinks of iniquity” and “dens of vice” were “contrary to good morals and decency.”[1] Saloons were unwholesome establishments where crime and debauchery flourished. They were places where the free and easy mixing of genders and races allowed naïve young men and vulnerable women to stray. To many, they were an unwelcome reminder that the City of Angels did not always live up to its name.

To many, saloons were an unwelcome reminder that the City of Angels did not always live up to its name.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the women who frequented the New Orleans House at 321 East Second Street were clearly all prostitutes. The saloon held rowdy dances where women, both “colored and white,” were boldly served beer directly at the bar. It was the hang out of the Frank Hays and Gurdine Horton gang of thieves and headquarters for Henry “King” Williams, an African-American horse trainer who had recently returned from the first of his three stints in Folsom prison.[2]

Large signs on the front door told the world that women were forbidden at the Basket Saloon at 719 North Alameda. However, the bar was surrounded by “cribs” and houses of prostitution to which the saloon’s owner had rigged an “electric annunciator.” If a woman, or her customer, was thirsty she could use the apparatus and a waiter would deliver drinks out the back.[3]

The old Philadelphia Beer Hall on 410 North Main Street hosted singing, dancing and boxing exhibitions that often ended with bloodied bodies being carted away on stretchers. Up the street, at 414 North Main, the patrons of the Alhambra were described as prostitutes, pimps, and the “riff-raff of the city”. Women waiters served drinks to the audience in a backroom where a “poor variety performance” was provided free each night. The audience for these and other entertainments was composed of the “scum of society."[4]

Despite the stories, the majority of saloons in Los Angeles were quiet places where men did little more than drink and talk. The city’s thirst was quenched at the Horseshoe, the Strasbourg, and the Depot on Alameda, the Progressive on Bellevue Avenue, the Office on Broadway, the Bouquet on Commercial Street, the Butcher’s Retreat on Macy Street, the Baker’s Home on First, the Monarch on Downey, and the Original Vienna Buffet on Requena, among many others. Occasionally, “short-skirted and high-kicking” women made things a little livelier, but only a handful of saloons appear to have been really rough.[5]

Details of the more notorious dives can be found in the pages of the Los Angeles Herald and Los Angeles Times and in Police Commission records that describe the mundane process of granting and revoking licenses.[6] In the 1890s, the saloon business dominated the commission’s weekly agenda. However, the saloons were not simply a police issue; they were political. Saloon owners, and more importantly alcohol distributors, had real power in the city. For many years, the question of how to regulate the saloons pitted the city’s religious leaders and Republicans against Democrats and Los Angeles’ immigrant communities.[7]

The good people of Los Angeles were not interested in attracting drinkers or the “bummer element,” but “substantial men of capital."

The debate about saloons in LA mirrored a national discussion. Alcohol consumption in the US peaked in the 1830s when, through a mix of beer, wine, and spirit, the average American drank more than seven gallons of pure alcohol a year. By the 1890s, this figure had dropped to a relatively sedate 2.1 gallons, a figure comparable to the amount drunk today.[8] However, while the temperance rhetoric was similar, alcohol was actually less accessible in Los Angeles than in other major cities. For much of the 1890s, the city had fewer than 200 saloons, serving a population of approximately 75,000, or one bar for every 375 residents.[9] This is far less than the city of San Francisco where, at about the same time, there were more than 2,000 saloons for a population of 234,000, or one bar for every 117 man, woman and child.[10]

So why such concern about drinking in Los Angeles? A hint can be found in a sermon from 1890 when Reverend Hutchins of the First Congregational Church told his flock that “to our friends in the East, Sabbath breaking, murder, and crime are associated with the word ‘California’”.[11] The availability of liquor might dampen the flow of newcomers. The Reverend, like other city leaders, was afraid that the population boom that would make the city rich might not happen if the right kind of American could not be persuaded to come west.[12] The good people of Los Angeles were not interested in attracting drinkers or the “bummer element,” but “substantial men of capital” whom, it was believed, would not “pitch their tent towards Sodom and their families towards perdition” without strong liquor regulations.[13]

In 1883, California had been the first state in the nation to eliminate Sunday prohibitions on businesses, including saloons.[14] However, cities were allowed to make their own laws and the topic was discussed for close to a decade by city leaders.[15] A large and vocal group of LA citizens wanted to simply close the saloons – all of them. Others suggested that their numbers should be limited. Still more argued that if the bars were closed, the women who worked them would ply their trade on the streets and in public. Surely, this was a greater evil. There were also others who would miss their afternoon tipple.

After a good deal of huffing and puffing, the City Council decided that, rather than make the decision themselves, they would call for a special election that would authorize them to close the saloons on Sunday. Mayor Hazard initially vetoed the idea, suggesting that there was no law that provided for this kind of election.[16] Hazard later relented under pressure from religious leaders and an election was scheduled for November 18, 1890. The ordinance passed, but was again stalled by Hazard, who argued that individual businesses had the right to set their own hours. After several days of mayoral “wobbling,” discussions with the council and representatives from both sides, the Los Angeles Times declared that the “agony was over” when the mayor agreed to authorize the new Sunday closing law.[17]

With the new law in place, the issue switched from regulation to enforcement. Policemen were regularly sent to investigate saloons accused of selling alcohol beyond the permitted hours. They often found closed doors, but the laughter and clinking of glasses continued inside. In the years following passage of the new law, little appeared to change in Los Angeles. This situation set the stage for other groups to take charge. In 1896, members of the Parkhurst Society spent a “fortnight of dissipation for the betterment of the morals of the city.”[18] Their methods would challenge the principles of Los Angeles’ polite society and test the limits of the city’s courts.

To be continued...

[1] “Dens of Vice: Disreputable Dives That Need Attention” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Feb 4, 1895 pg. 2; “At The City Hall: Police Commissioners. Numerous Applications” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Oct 21, 1896 pg. 8; “A Sink of Iniquity” Los Angeles Herald. March 23, 1890, pg. 3

[2] “Closing The Dives: Disreputable Saloons” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Sep 6, 1893, pg. 7; Henry King Williams was born in Florida in 1869 and is first recorded in the Los Angeles City Directory in 1893. He served 3 terms in Folsom State Prison and another in San Quentin for robbery.

[3] While there was no law specifically prohibiting women from going to a saloon, the news coverage of the day seems pretty clear that only prostitutes would consider doing so. “Closing The Dives.: Disreputable Saloons” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Sep 6, 1893; pg. 7

[4] “Police Business: Regular Weekly Meeting of the Commission” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Oct 30, 1890; pg. 3

[5] “Closing The Dives: Disreputable Saloons” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Sep 6, 1893, pg. 7

[6] Copies of the Los Angeles Herald are available online from the Library of Congress. The Los Angeles Times has been scanned and is available through the ProQuest database. The Police Commission archives can be found at the City of Los Angeles Archives and Records Center.

[7] “Sunday or No Sunday: Both Factions in the Fight Meet and Prepare for Battle” Los Angeles Times (1881-1886); Dec 13, 1881 pg. 3

[8] W.J. Rorabaugh “The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition”, Oxford University Press, 1979

[9] “Some Were Open: Saloons That Dispensed Liquid Refreshments” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Sep 16, 1895 pg. 8

[10] Zeitlin, Jeremy “What's Sunday All About: The Rise and Fall of California's Sunday Closing Law” California Legal History, Vol. 7, pp. 355-380

[11] “The Sunday Saloon: Receives Attention from Rev. Dr. Hutchins” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); May 26, 1890, pg. 2

[12] “Sunday Closing: The Meeting of Last Friday Afternoon” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); May 18, 1890 pg. 6

[13] “Sunday Closing of Saloons: To The Legal Voters of the City of Los Angeles” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Nov 15, 1890 pg. 3

[14] Alan Raucher “Sunday Business and the Decline of Sunday Closing Laws: A Historical Overview”, 36 Journal of Church and State 13, 18 (1994).

[15] “The Council and the Sunday Closing of Saloons” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Aug 28, 1890 pg. 4; “Council: Important Measures Before the Honorables” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Jun 5, 1890 pg. 3

[16] “The Council and the Sunday Closing of Saloons” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Aug 28, 1890; pg. 4

[17] “Political: The Mayor Will Sign the Sunday-closing Ordinance” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Nov 29, 1890 pg. 2; “Stopped Wobbling” Los Angeles Herald., November 30, 1890, pg.

[18] “Reformers in Court: Appear as Prosecutors” Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Dec 5, 1896 pg. 5;

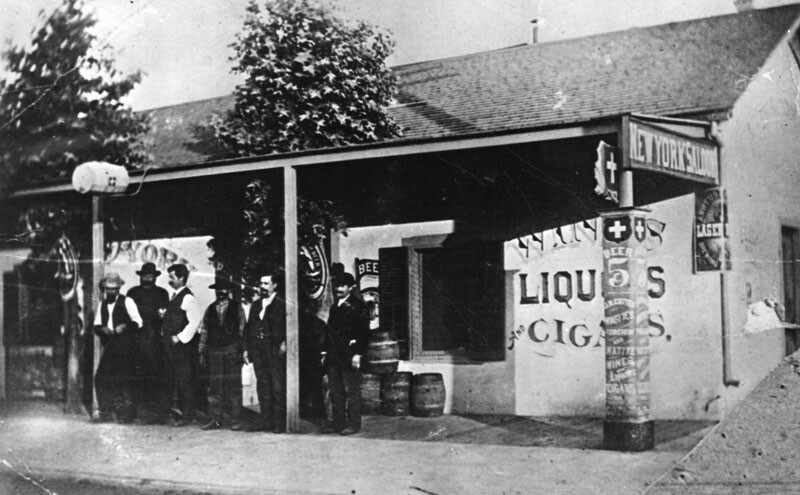

Top image: A saloon in Randsburg, Mojave Desert, ca. 1898. Courtesy of the USC Libraries – California Historical Society Collection.