How a Japanese American-Owned Real Estate Firm Broke up Racist Covenants in Southern California

Back in the mid-1940s, a Mrs. Lopez called up Kashu Realty in L.A.’s Crenshaw district and asked to speak with real estate agent Kazuo K. Inouye. Lopez lived on Rimpau Blvd in Mid-City and told Inouye that she wanted to sell her house, but insisted that she would only sell it to a non-white homebuyer because, when she purchased the house years before, she suffered the wrath of her neighbors, who took her to court in an attempt to prove that a Mexican American was not legally “white.” (She won the case.) Inouye gladly found a Japanese American family to buy her home, put up a Kashu Realty sign that said “sold,” and that's when the trouble started.

Soon, rocks were flying through windows of the house next door, which was owned by a Jewish couple. Apparently, a rival broker had hired four guys to break every window of the Lopez house, but in their haste and nervousness, the thugs had vandalized the wrong house. The Jewish couple suspected the man behind the bungled affair was the one they had witnessed standing across the street wearing a ten-gallon hat. He stood beside his 1947 Terraplane car with the door wide open, surveying the damaged windows with a look of profound disappointment.

Inouye called the cops and discovered the man in the "Texan's" hat was a broker on Adams Boulevard. "So, I found out who he was, and I called him," Inouye recalled. "I says, "You know, I was overseas [serving in the U.S. Army during WWII], and I killed a bunch of Nazis and fought for democracy." Then Inouye growled, "If you step one foot on the property — I got a German luger that I brought back. I'm going to shoot you between the eyes." He said, "Don't you threaten me." I said, "Look it. I'm going to sleep on the porch, and I'm going to wait for you. If you try it one more time, I'll put you away. Have you heard of a kamikaze? That's me. Are you afraid to die? I'm not afraid to die. Come on, try me out." He said, "Don't you threaten me."

Inouye's "kamikaze" stance apparently worked since he never saw the broker again.

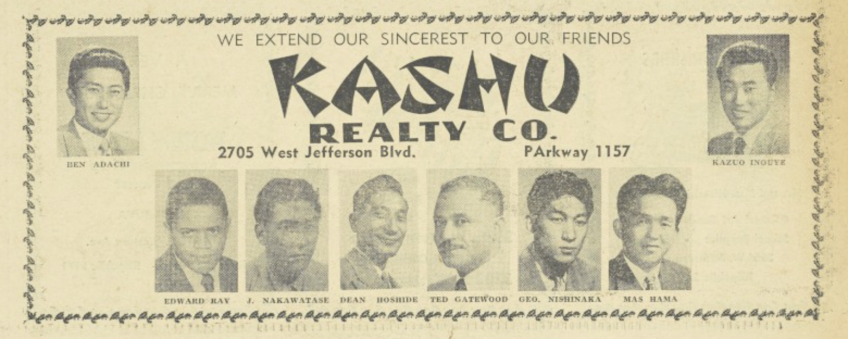

Kazuo K. Inouye was a second-generation Japanese American who made it his business to populate racially restricted Los Angeles neighborhoods with Angelenos of color, thus shaping the culture of the city block by block, for generations to come. He founded Kashu Realty in 1947 and sold a record number of homes to Japanese, Chinese, Black and Latinx first-time homebuyers in Leimert Park, Venice, Culver City, Baldwin Hills, Monterey Park and Crenshaw, helping to end decades of racial limitations to fair housing. His get-up-and-go mentality and abundant charm contributed heavily to the success of Kashu, where clients and staff alike described him as boisterous, good looking and ready with a story for every situation.

He was born in Los Angeles in 1922 to immigrant Japanese parents, Zenkichi and Toyo Inouye, and grew up between the cultural cacophony of multiracial Boyle Heights and the itinerant streets of Little Tokyo, where he worked as a produce market swamper. Inouye was determined from the start, learning sumo wrestling from his father and earning champion status as an All City gymnast and a 4th degree black belt in judo while in his teens. Nevertheless, Inouye faced constant racial discrimination, which only fueled his determination to persevere and be at the top. "My father always used to tell me that, ‘You're just as good as any 'hakujin,' which is American," Inouye once reminisced. "In fact, you're better than them, because you're Japanese."

During World War II, he was drafted into the U.S. Army's segregated, all Japanese American unit known as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. When the war ended, Inouye was 23 years old. He returned to L.A. and two years later, recognizing his community's hunger for stability and homes to call their own, he opened Kashu Realty, named for the old Japanese American moniker for "California.”

His real estate company would go on to help change the racial makeup of homeownership across Southern California. Sometime in the late ‘50s, Kashu Realty started to sell houses in West Adams and Leimert Park. The company placed ads in the Japanese American dailies and the African American newspapers like the California Eagle and Los Angeles Sentinel.

As Inouye explained, ”One black would move in, and they get so shook up that the whole block would sell. When I went back to my 25 year high school reunion (chuckles), my friends found out that I was Kashu Realty. He says, "Hey, Kaz, you're the blockbuster." I said, "No, no. I didn't do that. One black moves in, everybody else wants to sell. I just helped them." (chuckles) At one time around the '60s, we were selling 50 and 60 houses a month. That's every day, two and three houses."

According to historian Scott Kurashige, from 1950 to 1960, the population of Blacks and Asians in the Leimert Park neighborhood grew from a combined 70 persons to roughly 4,200 of each group, plus about 400 Latinx. Over time, Kashu Realty had satellite branches on Wilshire Blvd, Beverly, Hillhurst, Lankershim and E. 1st Street, plus offices in Sunland and San Gabriel/Monterey Park, where the firm performed similar feats.

Inouye certainly didn't do it all alone. He recognized that he needed a multiethnic sales force committed to persevere. Over the years, he employed Japanese, Black, Jewish and Chinese Americans, many of whom were immigrants working two or more jobs in addition to being on the Kashu salesforce. Encouraged, some Kashu office employees, like Florence Ochi and Victor Mizokami, pursued and obtained their realtor's licenses. In 1952, Chinese American Bill Chin joined Kashu Realty from his native Detroit and, in a few years, became Inouye's partner and a real estate legend in his own time. Chin, now 92 and still a licensed realtor, became a fixture in the Japanese American community and married a Japanese American who was born at the WWII Japanese American concentration camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. He's won all the industry awards, and in 1988, Chin became the first Asian American president of the Greater Los Angeles Realtors Association.

Angelenos of color have a long history of discrimination and displacement that has determined where they could claim their homes, businesses and cultural institutions and shaped their sense of local identity in a practice called redlining. By the time Kashu Realty was founded, racial covenants were still buried deep in the small print of home deeds. Federal law eventually banned the practice, but that didn't stop vigilantes from committing arson and other acts of physical violence against new homeowners of color moving in, or even their white neighbors who were open to selling to nonwhites. Maintaining discriminatory lending practices through the banks and barring real estate agents from selling homes to Blacks, Asians, other non-whites assured that these redliningpractices stayed firmly in place.

"First of all, we couldn't get a loan from the savings and loan," Inouye explained, "and the banks wouldn't lend us no money," but he learned ways to circumnavigate the system. He built a sales relationship with a wealthy white woman who loaned Kashu money on a first trust deed for early customers, before Western Federal Savings became the first mainstream bank to grant loans to Japanese Americans. Inouye's sister and brother in law, Tomiko and Roy Masao Mizokami, started an insurance company to secure fire insurance for new homes (which according to Inouye was necessary since they feared that their neighbors would burn their houses down). Since Tomiko was Inouye's only sibling, he deeply trusted her with the business and through the years, employed her as an office manager in addition to working together to insure new homebuyers. In 1951, the Japanese community formalized a century-old practice of pooling funds and taking turns borrowing sums (known as "tanomoshi") to start businesses or purchase property by forming the Japanese American Community Credit Union to assist people needing loans with competitive rates.

It was a two-way street. He's not just buying houses, he also had to find people willing to sell their houses. Racism can be named and shielded in many different ways.Daro Inouye, son of Kazuo Inouye

Inouye was also keen to work with homesellers who were sympathetic to racial integration. "It was a two-way street," reminded Daro Inouye, Kazuo's son, "He's not just buying houses, he also had to find people willing to sell their houses. Racism can be named and shielded in many different ways and redlining was consistently practiced in the 1950s. Sometimes people would flat out tell you my neighbors won't let me sell. My father had a lot of doors slammed in his face." Meanwhile, the government subsidized countless projects constructing suburban homes for whites as they fled Los Angeles proper, yet most people of color struggled for space in either public housing or rentals.

Since 1910, Los Angeles has boasted the largest population of Japanese Americans in mainland U.S.. This first-generation immigrant workforce vastly contributed to the city's fishing, agricultural and produce marketing, and gardening industries. Early Japanese residents rented rooms in the segregated neighborhood downtown known as "Little Tokyo" until they married and began families. Thus began an expansion into small enclaves that welcomed non-whites, such as Boyle Heights, Sawtelle, Uptown, or near the fishing and cannery operations on Terminal Island. Despite restrictive immigration and landownership laws, such as the Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning land or holding long-term leases, or acquiring agricultural lands, the Japanese community developed workarounds, including placing land in the names of their Nisei children who had U.S. citizenship.

Sadly, upon returning to L.A. after years of wartime confinement, the Japanese were never able to regain that prewar prominence in the agriculture and produce industry. Instead, using their experience in horticulture, many immigrant Japanese worked as landscapers, gardeners and domestics for wealthy white homeowners, which encouraged resettlement further from their previous community hub downtown to be closer to their client's homes. In some cases, labor was exchanged for free room and board, which cut monthly expenses down tremendously and allowed enterprising Japanese to slowly build their savings.

By working tirelessly and pooling their combined funds, by the mid-1950s, Japanese families were finally positioned to purchase houses. To meet the postwar housing boom, numerous Japanese American real estate companies opened, which played a crucial role in developing properties and opening doors to families of color who were buying their first homes. This led to a migration of Japanese Americans and Blacks into the Southwest (known as "Seinan" for locals), Venice-Culver and Crenshaw districts after the war, just as urban renewal downtown began tearing down Little Tokyo for city expansion.

Newlyweds Yaeko and John Nagafuchi bought their first and only home in May 1967, moving from a cramped apartment to a three-bedroom house on Potomac Avenue in the popular Crenshaw neighborhood. "When we first saw the house we fell in love with it. Of course it looked like a castle after living in two apartments prior to the house," reminisced Yaeko fifty-five years later and still living in her home. Wounds from the years their families spent incarcerated in World War II U.S.concentration camps at Heart Mountain, Wyoming and Poston, Arizona were still raw, but like so many Japanese Americans moving back to L.A., it was a return to home.

However, returning Japanese Americans quickly learned that L.A. was caught in one of the worst housing crises in the country — while they were pushed off the West Coast by the U.S. government, others were lured to California by jobs in the booming military industry. Many found that their stored belongings and other assets had been stolen or vandalized while exiled or were greeted with fierce discrimination and acts of terrorism. To ease the transition, temporary non-government hostels and emergency housing in trailer parkers and former Army barracks opened. Those who could rent apartments or rooms in boarding houses often went back to their pre-war neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights or the West Jefferson area. Others moved to the South Bay's Gardena and Torrance, where employment and housing restrictions were more relaxed.

Like Kaz Inouye, John was a WWII veteran. Many returning white veterans enjoyed the benefits of the G.I. Bill, which promised millions of veterans government aid for higher education and home-buying to its vets and acted as a gateway to homeownership for a generation. However, the guaranteed veteran benefits did not fund the loans directly. Veterans still had to secure financing from financial institutions, which was practically impossible for Asian American veterans, or even an Olympic diving champion like Sammy Lee, whom Inouye eventually represented.

Inouye later served as broker/developer for postwar houses in the area along the Centinela Avenue corridor. Building new homes catering to Japanese cultural needs meant including a big kitchen that could fit a table for the family to eat together at and lower countertops. Because Japanese women had shorter legs, the shelves and sink had to shrink to accommodate their diminutive heights. Outside, Inouye directed the homes to have a carport and a double garage with extra tall doors so the Japanese gardeners could drive in with their trucks loaded with brooms and lawnmowers.

"And the Japanese gardeners would [say], "Oh, kore wa ii. Oh, my God!—just want, I wanted"—I tell him, " Ojiisan, you know you don't have to take your brooms down. You can go in with your rack." Then we sold all the 10 houses. After that, then I started the building business. I started building myself and with a hakujin contractor, superintendent. We built a lot of homes. We called them Kashu homes over there."Kazuo Inouye

With this large influx of educated, professional people of color, the neighborhoods themselves began to change and businesses in Crenshaw in particular, grew to reflect its Japanese and Black population. Crenshaw Square, a commercial development near 39th street and Crenshaw Blvd, built in 1959, was one of the first Asian American mall courts ever built. Emy Murakawa recorded some of her Crenshaw Square memories in an essay originally published by the Venice Japanese American Cultural Center, "Crenshaw Square was originally conceived and planned to become the Little Tokyo of Midtown. Lots of Japanese shops and restaurants were there. Food Giant Market was there. It had its own Obon Festival and carnival. All the apartment houses with owners' units on Bronson immediately behind Crenshaw Square were owned and rented by Japanese, and there was always a waitlist at Cren-Star Realty. Jefferson Boulevard was busy with Japanese establishments, too.Who remembers Tamura Furniture, Koby's Drug Store Dr. Mizunoue's office, Dr. Munekata's office, Paul's Kitchen and Enbun Market across the street, and George Izumi's original Grace Pastries? Crenshaw Square boasted a Sumitomo Bank, and Bank of Tokyo was on Jefferson. There were two Japanese theaters, too— Toho La Brea and the Kokusai Gekijyo."

The Japanese gardeners would [say], 'Oh, kore wa ii. Oh, my God! — just what I wanted'Kazuo Inouye

By the mid-'60s, these racially integrated neighborhoods began to feel the strain. In 1952, a new immigration act was passed that formally ended Asian exclusion as a main pillar of U.S. immigration policy, even though it simultaneously strengthened the powers of the government to detain suspected subversives, echoing the arrests of Buddhist priests, Japanese language and martial arts instructors and other community leaders, immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The Act allotted immigration quotas to Japan and other Asian countries and eliminated race as a qualification for U.S. naturalization, which allowed Japanese and other immigrant Asians eligible to become American citizens for the very first time. s Japanese Americans gradually gained acceptance in the dominant culture, white efforts to further isolate and contain Los Angeles' Blacks intensified to the point of violence, illustrating the real and lasting impacts of institutional racism. "It was the beginning of the sansei (third-generation Japanese American) exodus," remembers Ken Kunishima, who moved to the neighborhood when he was eleven. "The Nisei stuck around Seinan area, that's where their roots, where their friends were. Some of them would move with their Sansei kids to Orange County, but the Nisei parents hated it. For them, it was very boring and they wanted to go back to the Crenshaw area." In 1980, Inouye and Chin decided to divide up the remaining satellite offices and to go their own ways. Inouye rebranded the business Kashu "K" (for Kazuo) Realty and Chin named his business ERA Kashu, joining a national franchise of associates.

True then as it is now, there is no sweeter prize for the Japanese immigrants who had suffered through the racism, exclusion, and wartime exile, than to hold the keys to their own home at last. It is a dream that Inouye and many others in his circle helped realize for many. "[My father] loved the business," says Daro, "loved the fact that he was able to have satisfied customers and could speak Japanese. He had no sense of borders."

Works Cited

Chin, Bill. Interview with Bill Chin with Patricia Wakida. 6 January 2022.

Horak, Katie. Asian Americans in Los Angeles, 1850-1980. 2018. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, http://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2019/19-0811_misc_10-7-19.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2021.

Inouye, Daro. Interview with Daro Inouye with Patricia Wakida. 2 January 2022.

Inouye, Kazuo K. Regenerations Oral History Project: Rebuilding Japanese American Families, Communities, and Civil Rights in the Resettlement Era : Los Angeles Region: Volume II. Kazuo K. Inouye Interviewee: Kazuo K. Inouye Interviewer: Leslie Ito Date: December 13, 1997. 13 December 1997, https://oac.cdlib.org/view?query=mizokami&docId=ft358003z1&chunk.id=d0e8239&toc.depth=1&toc.id=0&brand=calisphere&x=17&y=8. Accessed 3 December 2021.

Kunishima, Ken. Interview with Ken Kunishima with Patricia Wakida. 30 November 2021.

Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Mizokami, Victor. Interview with Victor Mizokami with Patricia Wakida. 5 January 2022.

Murakawa, Emy. “Have You Ever Wondered about Crenshaw Square?” Venice Japanese American Cultural Center newsletter, "Cultural Corner", circa 2000.

Nagafuchi, Yaeko. Interview with Yaeko Nagafuchi with Patricia Wakida. 13 December 2021.