Joshua Tree: How One Woman’s Work Preserved the Desert

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

Against an arid, broken background, the Joshua tree presents an otherworldly outline. Known scientifically as Yucca brevifolia, the plant grows wild across a small section of the Southwest and serves as a symbol of the California desert. While the plant's unusual appearance may have inspired Dr. Seuss's Truffula tree, the 19th century legendary California explorer John C. Frémont described its twisted trunks and bent branches as "the most repulsive tree in the vegetable kingdom." Topped with sharp, pointed evergreen leaves, in years with enough rain and a winter freeze, the tree blossoms in early spring bursting with clusters of white flowers and leathery seed pods.

Joshua Tree National Park, home to the eponymous plant, highlights a distinctive contradiction of the desert. Though at first glance the landscape seems barren and hostile, home only to stunted vegetation and twisted trees, a closer investigation reveals a history of exploitation of the region’s many natural resources.

By the time Minerva Hamilton Hoyt recorded her observations, the Pinto basin had hosted human inhabitants for millennia. Spearheads recovered in the region show that the first hunter-gatherers used the land’s resources between 4,000 and 8,000 years ago. More recently, the Serrano, Chemehuevi, and Cahuilla made their homes in and around the area now encompassed by the park. The Serrano arrived first, settling near an oasis they called Mara, which translates as the place of little springs and much grass.

More on California's Deserts and Lost LA

A reliable source of water and an abundance of edible plants, provided by the Joshua Tree’s seed pods, provided the Serrano with a relatively comfortable home. Bighorn sheep, deer and rabbits offered a diverse and self-replenishing larder. The Chemehuevi and Cahuilla bands moved into the area and mingled with the Serrano during the 1800s, marking their territory with petroglyphs. The discovery of gold and consequent influx of miners shattered the indigenous peoples’ way of life.

Though prospectors dug elaborate mines, few of the shafts proved profitable. Johnny Lang, a cowboy and miner, stumbled upon the most successful claim in the region by sheer luck. While searching for a herd of lost horses, Lang met prospector "Dutch" Frank. Frank explained that he had located a thick vein of ore but, having been threatened by local cattle rustlers, was afraid to begin mining. Lang purchased the claim from Frank, took on partners, and began the hard work of digging out the gold.

For nearly 40 years, the prospectors dug for ore, using mercury or cyanide to tease out the precious minerals and producing gold and silver worth several million dollars. The process took a significant toll on the environment. In addition to the chemicals used to separate out gold from the surrounding rock, the steam-powered machinery required huge amounts of water and wood. The miners harvested the nearby trees in such great quantities that the hillsides surrounding the mine remain only thinly-covered by growth today. The removal of plant life, though of a different type and for a different reason, motivated Hoyt to seek federal protection for the area.

Hoyt arrived in Pasadena with her husband in the late 1890s and quickly established her place among the city's high society. She indulged her passion for gardening and, like many others in southern California, developed a passion for desert plants. However, the growing popularity of cacti and other flora endangered the ecosystem. The rise of the automobile, along with miles of new roads spreading out from Los Angeles, allowed amateur gardeners and professional landscapers alike to easily collect the exotic wild plants. Widespread theft led to a precipitous decline in several species. The Joshua tree, in addition to being frequently targeted for vandalism, often fell victim to careless transplanting.

Like the Lorax from Dr. Seuss, the destruction of the region's plants convinced Hoyt to take action. In 1927, relying on her social status and connections, Hoyt began a series of public exhibitions dedicated to desert conservation and the showcasing of native plants. In the spring of 1928, two refrigerated train cars carried an assortment of large desert plants to the Garden Club of America's annual show in New York. Hoyt even arranged for fragile flowers to be flown to the show each day. With large mural backdrops, special lighting, and a selection of wildlife provided by a professional taxidermist arranged among the plants, the exhibit thrilled audiences. Hoyt's movement to protect the desert gained momentum. She drew in supporters and by March of 1930, she founded the International Deserts Conservation League.

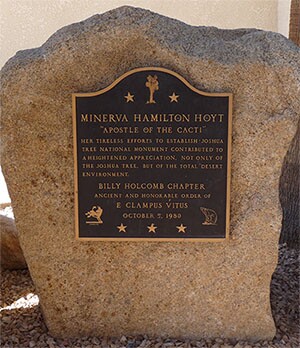

The league lobbied the National Park Service Director Horace M. Albright, seeking to establish a federally-protected park in the Pinto Basin area. However, land title disputes between miners and the state, along with a political dispute between the failing administration of President Herbert Hoover and Congress, proved insurmountable obstacles. Undeterred, Hoyt sought other opportunities, and in 1931, she met with Mexican President Pascual Ortiz Rubio in Mexico City. Staff from the Biological Museum of the National University of Mexico conferred to Hoyt the honorary degree of Professor Extraordinary of Botany and named a newly discovered cactus Mammillaria hamiltonhoytea in her honor. President Rubio called Hoyt “the Apostle of the Cacti” and announced a new park, a cactus forest comprising 10,000 acres. Invigorated by her success abroad, Hoyt redoubled her efforts in California.

A political shift worked in Hoyt’s favor. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, along with his Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, was eager to expand the National Park Service. Hoyt presented Roosevelt and Ickes with extensive research from the desert including black and white photographs showing the scenic expanse, color photos of the various exotic plants with written descriptions, and an evaluation of the recreational possibilities. Hoyt convinced the men, and the project moved to the next step.

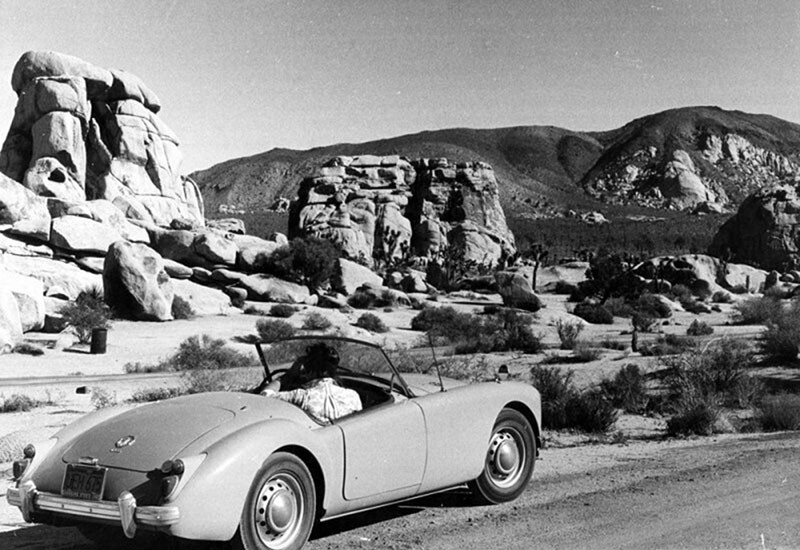

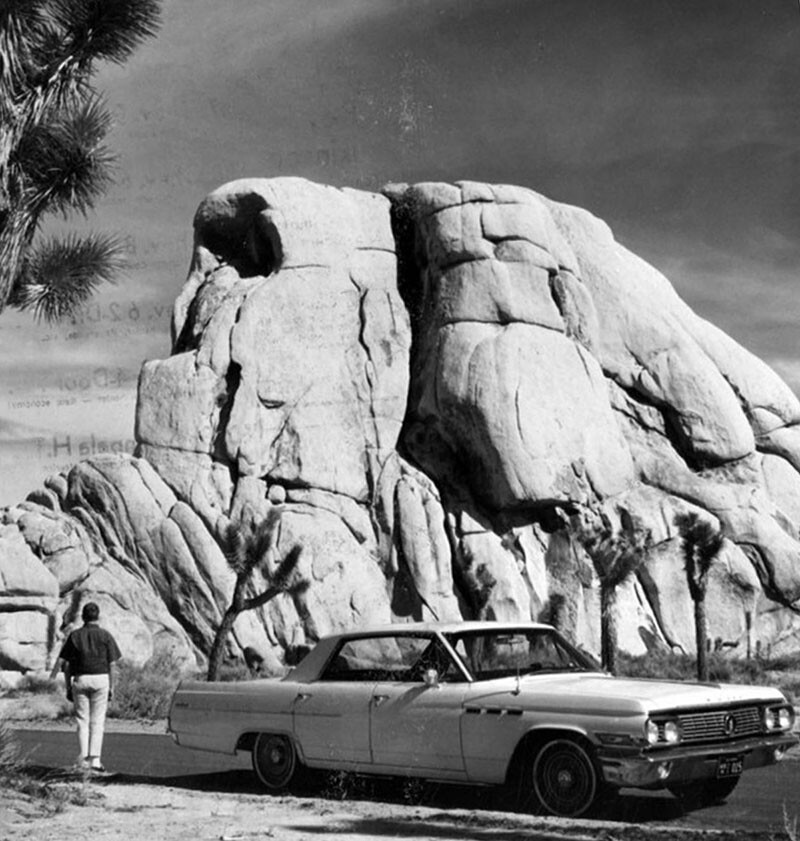

Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park Roger W. Toll joined Hoyt for an inspection of the proposed park in March of 1934. Traveling by way of Hoyt’s personal touring car, Toll spent three days in the open back of the vehicle, nearly freezing in the cold spring air. Few plants were in bloom, and Toll was unimpressed. Still, Toll determined that four species, including the Joshua tree, deserved federal protection. Toll’s recommendation carried weight and the process of establishing a protected area began.

Resolving the land disputes took months but on August 10, 1936, Roosevelt signed the declaration creating Joshua Tree National Monument. Hoyt had succeeded in her quest to protect the desert. The area gained even greater protections when President Clinton signed the California Desert Protection Act of 1994, expanding the site and officially establishing Joshua Tree National Park. Yet, even with federal protection, the Joshua tree remains threatened.

A bellwether species in a particularly delicate environment, both the Joshua tree and the wildlife dependent on the plant are at tremendous risk due to climate change. Biologists, botanists and rangers report that rising temperatures, decreasing rainfall, and the resulting increase in wildfires have led to significant declines in new growth and a greater than average dying off of mature plants. Industrialists and interest groups, attempting to open more protected desert habitats to mining and off-road recreational activities, continue to challenge the more recently established Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan designed to preserve the park's ecosystem. Minerva Hamilton Hoyt’s vision and passion led to a national park but unless the fight for conservation continues, the Joshua tree itself might go the way of the Truffula.

Top Image: The landscape near Barker Dam in Joshua Tree National Park | Liz Warner