How the Town of Sherman Became the City of West Hollywood

On Nov. 29, West Hollywood celebrates its 30th anniversary as an independent, incorporated city. Although the municipality is one of the youngest in Los Angeles County, the town from which the city sprang -- originally a settlement for railroad workers -- dates back to 1896.

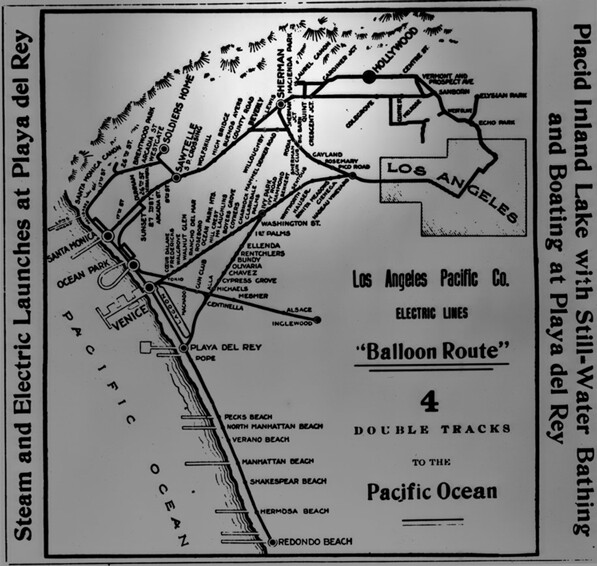

West Hollywood owes its existence to one of Southern California's first interurban electric railways, the Pasadena and Pacific. Assembled by Moses H. Sherman and his brother-in-law Eli P. Clark from failed and fragmentary predecessors, the Pasadena and Pacific connected the booming city of Los Angeles with the beach town of Santa Monica. Along the way, it crossed a sprawling coastal plain dotted with marshes, tar pits, and citrus groves. Today's Santa Monica Boulevard traces the railway's route across what was then called the Cahuenga Valley.

Early descriptions of "The Cahuenga," situated at the base of the Hollywood Hills, praised the area's fitness for agriculture. "One of the most attractive sections of Southern California, comparatively free from frost," the Los Angeles Times wrote of the area in 1897. "Here a specialty is made of raising winter vegetables for shipment to the East and North. Lemons are also successfully raised here." Originally settled by L.A.'s indigenous Tongva people, and later part of Rancho La Brea and Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, the Cahuenga Valley was sparsely settled as the turn of the twentieth century approached.

The introduction in 1896 of a water delivery system by John Pirtle's West Los Angeles Water Company made more intensive development possible. That year, Sherman and Clark built a rail yard and power plant at roughly the midpoint between Los Angeles and Santa Monica, where today's Santa Monica and San Vicente boulevards intersect.

Rehearsing the later development of the San Fernando Valley, which also depended on water, railways, and land speculators, Sherman and Clark platted a small town adjacent to the rail yard. Residential lots sold for $150 and were available for a $10 down payment with $10 monthly payments to follow. Soon, from the rail yard sprouted a small working-class town populated by railroad workers and their families, just to the west of today's San Vicente Boulevard. The town took the name of its co-founder: Sherman.

On January 1, 1897, the Times printed one of the earliest known descriptions of the new town: "About halfway between Santa Monica and Los Angeles is the powerhouse of the [railway] line, around which a little settlement known as Sherman has sprung up. The introduction of water for irrigation into this valley, which has just been accomplished, will undoubtedly tend to its rapid settlement, so that before many years the foothills will present an unbroken succession of beautiful suburban homes."

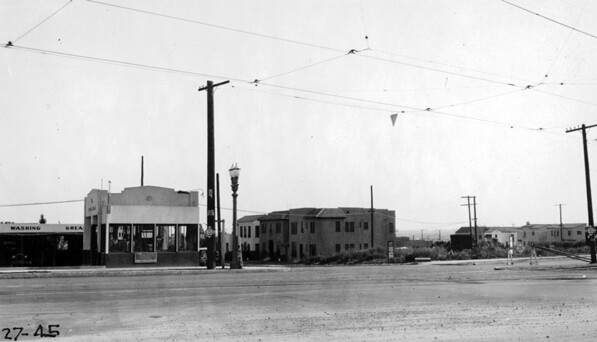

For years, farms and open fields separated the town of Sherman from the neighboring communities of Colegrove and Hollywood (an independent city from 1903 to 1910). Though connected by the tracks of the Pasadena and Pacific—later bounded on each side by paved roadways for motor cars and named Santa Monica Boulevard—it was not until the early 1920s that the growing Los Angeles metropolis met the street grid of Sherman.

Beginning in 1922, Sherman's population boomed. As the town's development began to merge with that of Hollywood, by then a part of the City of Los Angeles, some in both Sherman and the metropolis began speaking of annexation.

Los Angeles promptly annexed several large but mostly vacant tracts surrounding Sherman; the 1,203-acre Fairfax district became part of Los Angeles with the unanimous approval of its 16 residents, and a 7-0 vote joined the 430-acre Melrose district with L.A.

L.A. easily incorporated these vast tracts into its city limits without contention, but Sherman was an established community with an independent identity, and the issue of annexation divided Sherman's population and business interests. Realtors supported it, arguing that future development depended on access to Los Angeles' sewer and fire protection services. Sherman's Board of Trade and Chamber of Commerce opposed joining the city, however, fearful of increased property taxes.

Ultimately the anti-annexationist forces prevailed. Instead of relying on L.A.'s utility connections and public services, Sherman financed construction of its own sewer system and relied upon the county for police and fire protection services.

Sherman may have valued its independence, but it was less attached to its name. As motion picture stars moved into the adjacent Hollywood Hills and Beverly Hills communities, some Sherman residents sought to soften the rough edges of its image by changing the community's name and stressing its association with its affluent neighbors. Others, however, preferred to keep the town's original name out of respect for Moses Sherman, still alive at the time.

The Aug. 23, 1925 Los Angeles Times reported on the controversy: "Like a healthy, outdoor child, Sherman has suddenly burst all her old dresses and thinks while she is getting a wardrobe, suitable for a fully grown girl, she might as well discard plain 'Mary' and become up-to-date 'Marie.'"

"Mary" eventually lost out to "Marie." Residents mooted several alternatives, including Beverly Park, East Beverly, and Magnetic Springs, but in 1925 the town renamed itself West Hollywood, a moniker pioneered earlier in the decade by the West Hollywood Realty Board.

The tracks running down the center of Santa Monica Boulevard, meanwhile, became part of the Pacific Electric Railway in 1911 and carried red cars until 1941. They then remained largely unused for decades, serving the occasional Southern Pacific freight train through the 1970s. It was not until 1999 that the West Hollywood segment of the tracks were dug up and replaced by a landscaped median.

Over the decades, as the City of Los Angeles grew around it, West Hollywood survived several more annexation attempts. Residents also tried multiple times—in 1957, 1960, 1963, and 1966—to incorporate as an independent city. Backers of the 1966 cityhood drive cited as a benefit the ability to "pass stricter ordinances regulating the teen-age and long-hair activity," according to the Times.

By 1984, West Hollywood the arrival of new businesses and new residents had transformed West Hollywood. Gays and lesbians sought refuge from the regressive policies of Los Angeles and other cities in the island of county-administered land. There they joined Russian Jewish immigrants and a large concentration of seniors.

Soon a coalition—composed of residents concerned by out-of-control development, tenants anxious about the imminent expiration of Los Angeles County's rent control law, and gays and lesbians troubled by the possibility of annexation to L.A.—coalesced around the idea of cityhood. On Election Day 1984, with a population consisting of approximately 85 percent renters and perhaps 50 percent gays and lesbians, West Hollywood voted for incorporation and elected a majority of openly gay city council members. On Nov. 29, 1984, the town born of a rail yard became the City of West Hollywood.

Note: This post was edited Nov. 29, 2014, on the occasion of the city's 30th anniversary.