How the L.A. Public Library Amassed a Collection of 3.1 Million Historical Photos

Christina Rice, senior librarian of the Los Angeles Public Library's Photo Collection, stewards a collection of over 3.1 million photographs related to Los Angeles and its rich history. In the Central Library's bright, cheerful basement, carefully filed away, are images of every aspect of Los Angeles life. These photos tell the pictorial story of the City of Angels. But if a picture is worth a thousand words, so are the stories behind how the collection came to be.

Some of the first photos the burgeoning library received were unintentional donations. In 1900, the Los Angeles Times reported on the assorted hairpins, coins, and fabric swatches pressed between books returned to the library:

Photographs predominate, unmounted ones that are handy for book marks and in themselves present a wide range of variety. Babies, maids, wives and widows, pretty and ugly, old and young, go to make up the group and all of them nameless… photographs are kept longer, but in the end go to their destruction unless someone turns up and asks for them.

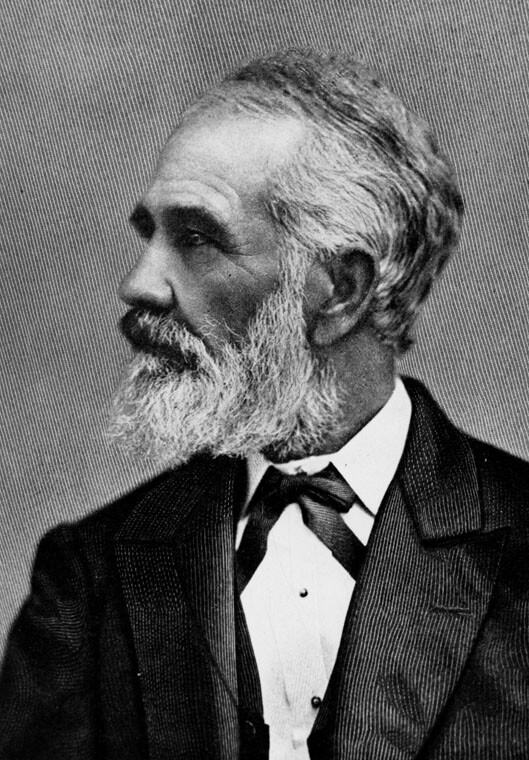

In 1914, the library received its first important (if unsolicited) photographic treasure trove. Chicago native Luther A. Ingersoll had moved to Los Angeles in 1888. As an employee of the Lewis Company, he was charged with writing histories of the L.A. area, such as "Century Annals of Santa Monica Bay Cities," for national consumption. During his decades of research, he had collected hundreds of images of pioneer Angelenos, their estates, and early public buildings. Some of these photos, taken by William M. Godfrey, were among the first developed on the West Coast. The donation was announced in the Los Angeles Times:

Los Angeles got a Christmas gift yesterday. Luther A. Ingersoll, for many years a resident of this city, and now living at Santa Monica, donated to the public library his historical collection of over 1,000 daguerreotypes, photographs and engravings, interesting manuscripts and other data bearing upon the early history of California and particularly Los Angeles. The collection is valued at more than $10,000 and has been accumulated during a residence here of over a quarter of a century.

The next year, the library would hold its first public exhibit of Ingersoll’s collection. Today, the collection continues to be an important link to our early history. “I’ve been told that in many cases we have some of the only known photos or only really accessible photos of some of these really early Los Angeles pioneers,” Rice explains. “Sepulveda, Pico, Lankershim, names people know from being stuck in traffic around the city.”

Despite this gift, the library would not actively seek photos for another twenty-odd years. “My understanding, and documentation is pretty loose, is the 1940s is when the library consciously started collecting photographs,” Rice says. “Two of the earlier collections we obtained were a group of photos taken under the federal writers’ project as part of the WPA, which we have identified more or less in our database as the WPA Collection.”

Over the years, photos have come from the most unlikely of places. In 1981, the library received a collection of around 150,000 historic photographs (of which approximately 116,000 are currently digitized) from the Security Pacific National Bank. The collection was donated after the bank’s archivist, Victor Plukas, decided he was ready to retire. “Banks were at one time really strong advocates of art and history,” Rice explains. “When they would open a branch in a community, and this was L.A. City as well as L.A. County, they would collect photos of the history of that neighborhood to display at their branches.”

The Security Pacific donation included the collection of photos closest to Rice’s heart. Published from 1946 to 1970, the Valley Times covered happenings in the booming San Fernando Valley of the postwar years. The newspaper’s morgue (archives) was acquired by Security Pacific in the 1970s, after the paper’s owner, Lammot du Pont Copeland Jr., was forced to file for personal bankruptcy. The morgue included 82,000 prints, 52,000 of which were taken by Valley Times photographers. “No story was too small for the Valley Times,” Rice says with a smile. “So, if Grandma is celebrating her 82nd birthday and you call the Valley Times, they would send a photographer. I just think its charming. It reflects a level of civic engagement I don’t think we see as much, but also just a level of charm. It’s like the sun was shining in the Valley a little bit brighter compared to this side of the hill – as reflected in the Herald.”

Indeed, if you are looking for noir L.A., you will find it in spades in the old wooden card catalogue that leads you to the endless stacks housing 2.2 million photos from the “moody,” tabloidesque, William Randolph Hearst-owned Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, with images spanning from the 1920s to the paper’s demise in 1989. “When people say ‘do you have a photo of my house?’ – if a movie star lived in your house, I say possibly,” Rice laughs, “or if somebody got murdered in your house. Then we’ll probably have a photo of your house in the Herald.”

The library actively sought the Herald’s morgue, which is so large it merits its own archivist, the delightful Wendy Horowitz. “I’m always finding stuff,” Horowitz says. “And every time I find something I run into Christina’s office and say look what I found! Look what I found!”

“It will be interesting with somebody, especially with actors – you will just get their entire life in your hands,” Rice says. “You know, you’ll get them really early on in their career, as they’re a supporting player or a starlet, then they hit it big, then you see the marriage, and then you inevitably will see them in divorce court, and then in the end you see a picture of their funeral. It’s fascinating – and also kind of weird. You have somebody’s entire life in a folder or in a box.”

While mammoth collections like the Security Pacific National Bank and the Herald-Examiner have inspired decades of research and study, some of the smaller, personal collections at the library are equally precious. These have been acquired in various ways – through wills, library initiatives, and in a few cases dumpster saves. Together, they form a patchwork that displays the vibrant artistic lives of dozens of Angelinos.

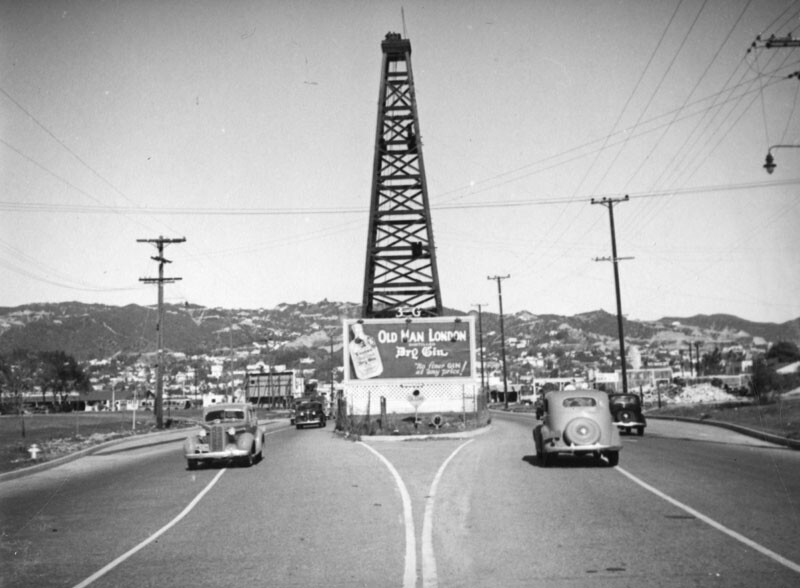

One of Rice’s personal favorites is the collection of Herman J. Schultheis, a German immigrant who lived in Los Angeles with his wife, Ethel, from 1937 until his disappearance in the jungles of Guatemala in 1955. Schultheis worked as an engineer for Disney, and pursued many hobbies, including archeology and photography. “His Los Angeles tends to be a working-class city beginning to show the signs of urban decay, but forging ahead with progress,” Rice says. “A land where beachcombers picnic in the shadows of oil derricks, vaudeville theaters have become homes to burlesque shows, and minority populations are displaced for the advancement of others.”

After Schultheis’ disappearance on an archeological exploration, Ethel stayed in Los Angeles. When she died in 1990, her estate was donated to a Catholic charity. Her husband’s 4,000 or so photos, many featuring the couple together, were eventually donated to the L.A.P.L. “There are so many photos of him and Ethel together, and everyone who works on this collection just falls in love with them,“ Rice says. “They’re so sweet.”

Other collections tell of seemingly ordinary Angelenos’ secret passions. Mildred Harris was a church secretary who took invaluable photos documenting downtown’s rapid post-war redevelopment. “The daughter of a Methodist minister called us,” Rice says, “and said, she was my dad’s secretary and we have these photos, and do you want them?”

Perhaps the most famous photographer to donate a group of photos was none other than Ansel Adams. “He was on assignment for Fortune Magazine in 1941 to shoot Los Angeles and the emerging aerospace industry,” Rice explains. “So, he took the photos and Fortune did run some of them. Then in the early ‘60s when he was getting ready to move to Monterey he came across the photos and contacted us directly.” However, Adams thought very little of these photos. “The donation letter actually says, “If you don’t want them put them in the incinerator,” Rice explains. Thankfully, the library kept the 217 images.

Today, the photo collection keeps growing, and many photos are available to view online. They provide documentary evidence of Los Angeles life over the past three centuries. “Our scope is contained to California, specifically Los Angeles, so that’s narrow in a sense,” Rice says, “but at the same time there’s so much going on in Los Angeles!”