How the Gleeful Aesthetic of L.A.’s 1984 Olympics Unified a Sprawling City

Looking back at images of the 1984 Olympics, you wouldn't think that it was designed at a cut price. Huge orange scaffolds featuring teal and silver-colored spheres towered above venues. Rows of yellow gazebos sat atop purple and mint green columns. Sonotubes all over California lined streets, sporting locations, entry gates: some circled with simple, contrasting hoops; others splattered with baby blue and vibrant orange, Pollock-style; others adorned with brightly colored stars or pastel pictograms, a twist on Games previous. This was Olympic psychedelia, a gleeful '80s aesthetic which underlined the complementary power of sport, culture and art.

While Mexico's designs in 1968 had pushed the boat out, the eclectic postmodernism of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics raised the mast, demonstrating what could be done with a coherent color palette and the unifying power of design. It would revitalize a bedraggled Olympic movement too.

Los Angeles' 1984 Olympic Committee primarily aimed for the Games to make money. While the '32 Games were constrained by the global economic climate, the '84 edition was constrained by the Olympic and international climate of the time. The world was in the depths of the Cold War, Ronald Reagan was president and the 1980 Moscow Olympics had been boycotted by American athletes due to politics. In many ways, the 1984 Olympics were a President's dream; a large-scale event which could export an image of American glory to a world of baying viewers. Reagan kicked off the Games with a speech; they were the first Games in history to be opened by a world leader.

The financially disastrous Montreal (1976) and Moscow (1980) Games were all too recent reminders for possible hosts of the financial consequences of a poorly-managed Games. Tehran, the only other potential host for '84, dropped out of contention due to the Iranian Revolution, leaving L.A. unopposed. After the 1980 Moscow Olympics boycott by the US, the USSR led a boycott which threatened to take the gleam off the Games, while L.A. itself was facing rising unemployment, widespread drug use, violent crime, aggressive policing, racial tensions and economic inequality.

Organizing committee president Peter Ueberroth wrote in the Committee's First Official Report (1980) that L.A. was aiming to construct an Olympics which "will serve as a prototype and encourage other cities to seek to host future Olympiads." While in '32 the Olympics were used by L.A., in '84, the relationship between host city and world was more mutually beneficial, though L.A.'s aims of revamp were much the same. It had a reputation as a sprawling, polluted city which lacked civic cohesion.

While just two cities bid for the 1988 Olympics in 1981 due to the financial pitfalls of the Olympics over the years, in 1986, six cities would submit bids for the 1992 iteration of the Games, such was the success of the '84 Olympics. They would make a profit of over $250 million with a chunk of that being put towards the establishment of the non-profit LA84 Foundation. However, while the Foundation claims to have put the proceeds towards youth sport, it's unclear how much of the profits went there due to the Foundation's opacity. A large chunk of the profit, as it tends to do, also went back to the IOC.

In order to turn a profit, the '84 Games were the first to be privately funded. They were revolutionary in terms of sponsorships and broadcast revenue, raking in $250 million from a deal with ABC. The commercialization wasn't subtle; Coca-Cola was the Games' official drink, FujiFilm was the "Official Film" (you know, for analog cameras) and McDonald's had a famous backfire. They lost a lot of money as they tried to cash in by offering a Big Mac, Coke or fries every time the US landed atop the podium. The US had a successful Olympics, and some McDonald's outlets ran out of burgers.

A City De-Sprawled by Design

L.A. had undergone drastic change since 1932. The city's population had tripled from just over 1 million people in '32 to about 3.2 million in 1984. Infrastructural changes had been wrung throughout the city and the state in the '60s and '70s, resulting in a much more dispersed Olympics than 1932's offering; only two new permanent structures were constructed for the '84 Games due to the prevalence of sporting infrastructure throughout Southern California and the Games' focus on financial prudence.

L.A. was exceptionally blessed when it came to sporting structures and had a range of venues which made it suited to a cut-price Games. From the iconic structures of the Rose Bowl and Memorial Coliseum, to several college stadiums; a regional park was even used.

Venues extended from Lake Casitas (canoeing, rowing) nearly 100 miles west of L.A. city to Coto de Caza (modern pentathlon) in Orange County and beyond; Harvard Stadium in Boston and the Navy-Marine Corps Stadium in Annapolis even hosted Groups A and B of the soccer tournament, ensuring some East Coast involvement. This was an Olympics designed to appeal; locally, nationally, internationally and financially.

The architects and designers charged with crafting the Games' visuals — Jon Jerde (JERDE), Deborah Sussman and Paul Prezja (SP&Co) — were faced with two major obstacles. Firstly, the scarcity of new constructions due to the Games' focus on a financially sustainable Olympics (it was also the first privately financed Games). Secondly, the stark distances between venues caused by L.A.'s continued urban sprawl since the '30s, which could potentially have created disparity in the Games' tone and messaging.

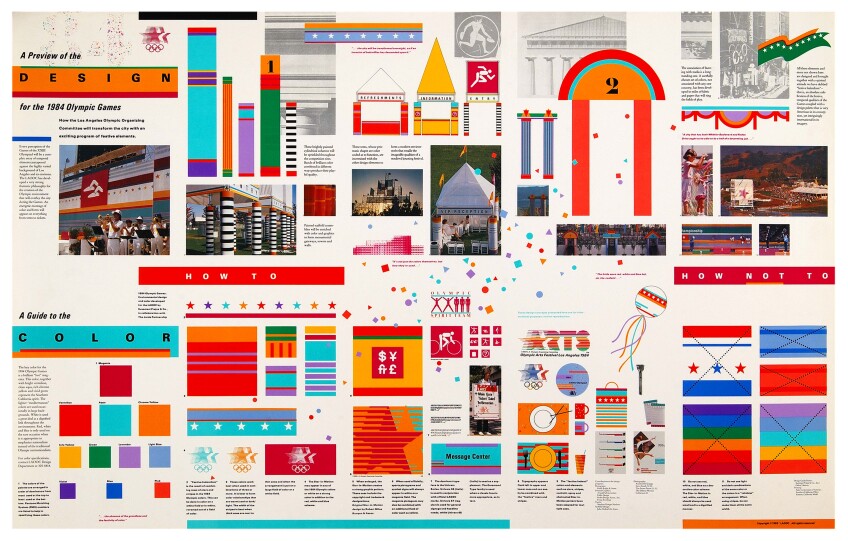

To overcome such issues, Jerde, Sussman and Prezja came up with a "kit of parts" design; a guiding design philosophy — an Olympic brand — made up of tents, banners, scaffolds and anything else architects could get their hands on, which was to be implemented at every Games venue.

In November 1982, the Design Coordination Guidelines were drawn up. They stated that "Everything associated with the Games must have a fresh, festive look to it that conveys the temporal qualities of the event. The whole city should look like (sic) a wonderfully colorful invasion of butterflies has descended upon it." The invasion was perfect for the small screen, too, fittingly for the first games to become a truly global television event. Prezja says that some sets and structures were placed strategically, according to where they would look best on television.

This design philosophy was defined by a set of iconography and pictograms that bore resemblance to each other without looking the same, "Jon Jerde's idea was that we would design these — as he called them — environments, and then we just tweak them all to look a bit different, so that's what we started doing in the design of tents," Paul Prezja explains; common tents such as hospital tents and concession tents that would be used throughout the Olympics were to have the same design all over the Games.

"We put together a fold out sheet and said, 'Here's where we're going'" Prezja says, "so everybody involved, all the architects that were brought in alongside us [about 27 of them], knew what to aim for." Many of them were working side by side, in the same building for a year or so before the Games, and it's perhaps this physical closeness that helped the designers ensure creative consistency throughout Olympic venues.

The mission was completely different from 1932's fairly centralized one. The previous Games had little impact, Prezja explains, "We researched '32, but we couldn't even find the Olympic site — the big thing for us was Mexico '68, because they did some very big and interesting things — using color a lot, for example."

It was this use of color amplified that made LA '84 a veritably visual experience. Not only did the colors transform L.A. county into a cohesive experience shared by spectators and athletes alike, it also changed the game for the Olympics that followed. The color scheme was termed "Festive Federalism" by Sussman; it incorporated bold use of magentas, yellows, aquas and oranges as base colors, giving classically patriotic designs a modern restoration, as well as incorporating the very well-received pictograms from the 1976 Munich Games.

Lingering remnants of the Panama-California Expo were there, too. The colors selected had ties to the SoCal region. Magenta and yellow are associated with the Pacific Rim, Asia and Latin America, while aqua is Greek and Mediterranean, a strong counterpoint to the warmer colors. If L.A. was a cultural melting pot, then so too was the Games' palette.

These striking colors, not traditionally associated with the Olympics, were chosen due to the sheer size of Los Angeles. "This thing was spread all over…you had to make something that would stand out and draw the venues together" Prezja outlines, "and locally, people told us that this was the first time Los Angeles was a unified whole, and it was, in a sense." L.A., which was so abundantly blessed with a sense of space, was finally given a unifying sense of place to complement it.

The designs weren't just well-received locally. Jerde, Sussman and Prezja were the subject of attention from publications such as the New York Times and the London-based Architectural Review. The success of the project was such that they would be awarded Design of the Decade by TIME Magazine. Jerde was named the first recipient of the USC School of Architecture's Distinguished Alumnus award in 1985 and would go on to design buildings all around Los Angeles County.

The success of '84's concerted design was no coincidence. Prezja and Sussman had experience in designing temporary exhibitions. "Some of the first jobs we got were trade shows, where we had to do things that could pack up and then come down…we made a kind of village for Warner Bros using tents, for example," Prezja explained. After Jerde presented the "kit of parts" idea to Harry Usher, right-hand man to chief organizer Peter Ueberroth, Usher suggested they try out the idea in competition with (their mentor) John Follis at the American Olympic trials a year earlier.

"We went all out," explains Prezja, "We did facades behind the bleachers, pediments and columns at the entry places, banners when the swimmers came on." Usher granted them the job, and it's perhaps this prior experience that ensured the eventual success of the Games' design philosophy.

Operational experience was at the time rather hard to come by when designing a mega-event, but by now it's been recognized by host cities as instrumental in hosting a successful Games. Russia — host of the 2014 Winter Olympics and 2018 World Cup — held a rather sizeable portfolio of medium-sized sports events beforehand.

The '84 Olympic Village was another example of sensible Olympic use of facilities. USC, the sports teams of which had benefited immeasurably from the construction of the Memorial Coliseum for L.A.'s inaugural Olympics, offered its campus for athletes to stay at, as did UCLA, CSULA and UCSB. In 2028, UCLA will again host athletes in its facilities, while displaced UCLA students will use some of USC's student accommodation.

It is perhaps striking that one of the most architecturally successful Olympics in modern history was one of the least architectural, at least in the narrow sense of the word. Constructions were avoided apart from two permanencies (a velodrome and an aquatic center). Instead, temporary architecture — facades, banners, sonotube columns, etc. were used throughout the event and either disposed of or auctioned off afterwards.

However, if we take architecture to encompass the use of constructions, space, color and the power of cognitive associations, then it's perhaps no surprise that LA84 set a precedent for future Olympics and mega-events. "Selbert Perkins did the 1994 World Cup, and they were very influenced by what we did, and did things of their own that added to it," explains Prezja, "And would London have used such bright colors if we hadn't first? I don't know."

There are a few important lessons which can be learned from the success of their designs. "It taught the architects that worked on it what you could do with something temporary," says Prezja, "I think it got people thinking about those kinds of things — our street banner program, for example; now signatory banners have become the norm." L.A.'s designs set a lot of little precedents while proving how a mega-event and a vast region could be unified by inexpensive design.

Deborah Sussman described her large, bright designs as "supergraphics". She once said that "the idea of supergraphics was not that it was just 'big' but that it was 'bigger' than the architecture." This was never more true than throughout L.A. for a few weeks, in 1984.

A Lack of Civic Legacy

Perhaps the main architectural shortcoming of the '84 Games is the lack of public legacy for the city of L.A.. "There was less focus at the time on the public realm and public space in general," explains Ken Bernstein, a Principal City Planner at LA City Planning Department, The [2028] Games really can and should pay more attention to a lasting design legacy in the public realm."

One thing that springs up for Angelenos when recalling the '84 Games, aside from the sense of cohesion throughout the city, is the free-flowing traffic, which calmed for two weeks after workers were encouraged to stay home and an intensively-planned traffic management system was enforced. "Where did you hide your famous smog?" Juan Antonio Samarach, IOC President, asked a luncheon audience of local officials on the last day of the Games.

That the smog eluded global attention was due to both intensive planning measures and widespread citizen compliance. Journalist Erin Aubrey Kaplan wrote that there was "citywide surprise and pleasure at the fact that traffic turned out to be so benign; I believed that I had a part in pulling off the miracle simply by staying home and not contributing to the congestion that never happened. Ironically, that non-activity engendered a great feeling of collective accomplishment that I haven't really felt since." Traffic management added to the ephemeral feeling of regional achievement that was catalyzed by the Games' design philosophy. However, the streets and freeways would return to their jam-packed norms after the Games, something L.A. has struggled with in the decades since.

Legacies also failed to materialize for the good of citizens in other areas; laws were brought in prior to the Olympics that allowed the LAPD more powers, such as the expansion of 'gang sweeps' for the duration of the Games. Once the Games ended, anti-syndicalist laws were revived to maintain the security policy instigated during them.

Mass arrests became more common and complaints about police brutality increased 33% between 1984 and 1989. Such laws also enabled Operation Hammer, an initiative aiming to crack down on gang violence at the height of which nearly 1,500 arrests were made in a single weekend, a large majority of which resulted in no charge being filed. Other previously unanticipated steps included the federal government supplying the LAPD with a military-grade tank and other military arms.

By 1990, over 50,000 people had been arrested in raids which largely depended on racial profiling and targeting of Black and Hispanic youths. This, coupled with up to 45% African-American unemployment in SoCal and relentless police violence, would eventually culminate in the 1992 Rodney King riots.

Such issues have been echoed contemporarily as the Los Angeles Police Department faced widespread criticism during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, resulting in L.A. City Council exploring unprecedented cuts to the police budget. However, the Olympics are often used by governments as a means by which to justify extra police or military involvement.

Those against the 2028 Olympics have voiced concerns about the safety of residents, undocumented immigrants and low-income communities if the '28 Games are used to justify expansion of the LAPD by 3,000 officers as Senior Lead Officer for the L.A. Neighborhood Shawn Smith indicated might happen earlier this year.

Issues have clouded the Olympic movement since 1984 too. In the Nov. 1982 Design Coordination Guidelines, 1984 was described as a great opportunity to "move away from the ego architecture of recent Olympics." However, in the Games since — Athens, Rio, London, Sochi and numerous others — such ego has returned, as the spectacles have cost billions of dollars of public money. Countless more has gone missing, and typically, local communities have hardly seen a penny of it.

As L.A. gears up for a 2028 iteration which will again focus on financial prudence, it remains to be seen whether the Games can cause citywide change lasting longer than two weeks.