How the 15th Amendment Came to Los Angeles

At four o'clock on the morning of April 12, 1870, dozens of explosions echoed through the dark and empty streets of Los Angeles. The booming noise might have startled the town's horses and roused some of its residents, but this wasn't the sound of violence. It was the sound of freedom. The blasts were coming from the top of Bunker Hill, where some fifty people – almost half the city's African-American population – gathered to watch as anvils were shot into the air over and over again in celebration of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The festivities lasted well into the evening and even the following morning. That night, hundreds of white Angelenos joined the celebrants at a grand Ratification Ball that culminated in a midnight supper.

The amendment's ratification was certainly something worth celebrating. The Fourteenth Amendment had guaranteed citizenship since 1868, but California, as with most states, continued to deny African-Americans one of the fundamental rights of citizenship: the right to vote. Now – over the objections of the Democratic politicians who dominated local politics and were generally hostile to civil rights – black Angelenos possessed that right.

Or did they?

Just four days later, Lewis G. Green walked into the county courthouse and attempted to exercise the right so many Angelenos had just celebrated by registering to vote. The county clerk refused. The reason? Green was black.

The 43-year-old barber, who had helped organize the April 12 festivities, was also a leader within Los Angeles' African-American community. As Ralph E. Schaffer recounts in "Implementing the Fifteenth Amendment in California," it's likely that Green's attempt to register was an orchestrated moment of activism. For Green wasted no time in following one courageous step with another: he sued clerk Thomas Mott in county court, petitioning Judge Ignacio Sepulveda for a writ of mandamus that would compel Mott to add his name to the electoral roll.

L.A. Electoral History

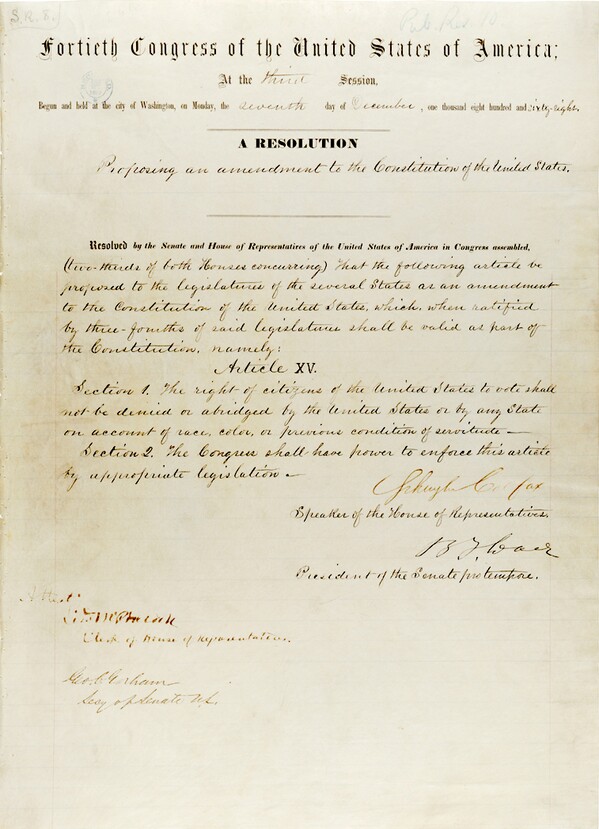

Green's attorney, a young lawyer (and future USC founder) named Robert Widney, pointed to the plain language of the Fifteen Amendment. "The right of citizens of the United States to vote," it said, "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

Mott and his attorneys with the firm of Glassell, Chapman, and Smith countered by citing state law. The 1849 California state constitution limited voting rights to white male citizens, and a state statute prescribed fines for any clerk who registered someone not eligible under the state constitution. In the absence of an act of Congress designed to compel cooperation by state officials, Mott's counsel argued, the newly passed amendment was simply a general constitutional principle that didn't supersede the state's restrictions on voting rights.

Sepulveda – who, like Mott, was a leading figure within the local Democratic party – agreed. On April 28 he denied Green's petition.

Congress soon intervened, however. Its Enforcement Act of 1870 answered the arguments of officials like Mott with specific penalties for noncompliance. President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law on May 31.

Mott relented. On June 21 he inscribed Lewis Green's name on the Great Register of voters – though not without protest. Next to the registration numbers of Green and other black voters, Mott apparently wrote "C" for "colored" and also noted that he had assented to their registration "per Fifteenth Amendment." Still, Green and his compatriots had finally secured their hard-won right to vote.

Of course, that right did not yet extend to L.A.'s entire African-American community. Its most noted philanthropist, Biddy Mason, still couldn't register, nor could another leading entrepreneur, Winnie Owens. In fact, half of black Los Angeles was still denied the franchise. Women – regardless of their race – would remain ineligible to vote in California for another 41 years.