How Santa Monica Almost Became a Commercial Harbor

Today, the seaside community of Santa Monica could hardly be more different from the sprawling harbor district adjacent to San Pedro. An industrial landscape dominates the Harbor Area--the beaches of the former San Pedro Bay have been converted to landings, and its seas stilled by breakwaters. Santa Monica's landscape, meanwhile, retains the marks of its resort-town past with white sand beaches, a carnival pier, and a busy retail district.

But in the late nineteenth century, Santa Monica very nearly supplanted San Pedro as the region's commercial shipping hub. If a late-nineteenth century political struggle between the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce and the Southern Pacific Railroad had ended differently, it is Santa Monica that might today be crawling with semi-trailer trucks, cranes, and container ships.

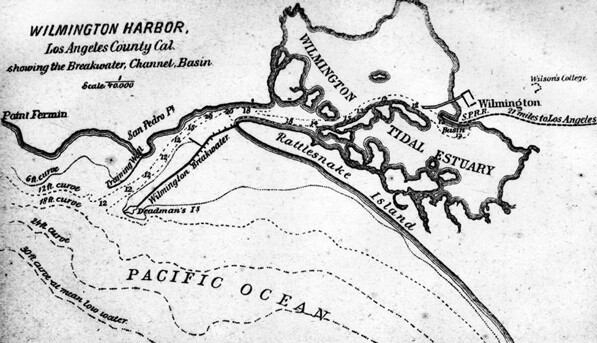

Los Angeles has always lacked a natural harbor. Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo first identified San Pedro as a potential harbor in 1542, but conditions were less than ideal; a sandbar in the middle of the bay impeded navigation, the shore was lined with mudflats, and the Palos Verdes headland offered only partial shelter from winds and seas. With no deep water port, freighters delivering goods to Los Angeles were forced to anchor in San Pedro Bay, where they were met by small boats, known as lighters, that then carried the ships' cargo to shore.

As Los Angeles entered in the industrial age in the mid-nineteenth century, its lack of a safe harbor worried the city's business interests; L.A.'s chief rival to the south, San Diego, boasted the second finest harbor in the state, after San Francisco's.

If topography did not provide a natural harbor, the city decided, then it would create one itself. In the 1850s, Phineas Banning purchased land alongside the San Pedro Bay's tidal estuary, dredged a channel through the marshes, and built a landing. He also constructed Southern California's first railroad, the Los Angeles and San Pedro, to transport goods between the city and the coast. Subsequent investments in the port by the Army Corps of Engineers and the Southern Pacific Railroad, which bought Banning's 21-mile line in 1872, seemed to ensure that San Pedro Bay would be the site of the region's harbor.

Everything changed in the early 1890s, when the Southern Pacific abruptly abandoned the Wilmington and San Pedro ports and instead began routing its freight trains to Santa Monica. (The SP used the tracks of the former Los Angeles and Independence Railroad along the same right-of-way that soon will carry Metro's Expo Line.)

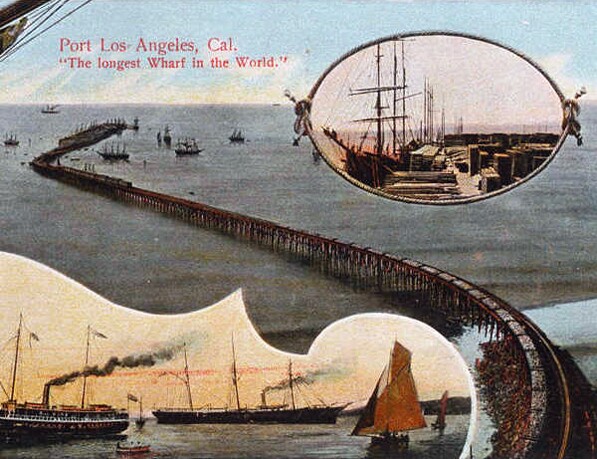

Southern Pacific president Collis P. Huntington partnered with Nevada Senator John P. Jones, the founder of Santa Monica, to build a mile-long, double-tracked wharf into the Pacific Ocean just north of Santa Monica Canyon. At 4,600 feet, it was at the time the longest wharf in the world. Even more vulnerable to wind and waves than San Pedro, the pier--named Port Los Angeles--nevertheless succeeded in luring shipping traffic away from San Pedro Bay. Jones and Huntington then used their considerable political influence to block the construction of a breakwater in San Pedro Bay and argue instead for one off the coast of Santa Monica.

Competition from other railroads likely prompted the Southern Pacific's sudden change of heart. At the time, a syndicate likely associated with the Union Pacific was building a line to San Pedro Bay. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, meanwhile, had drafted plans for Port Ballona, a shipping center to be located at the site of today's Marina Del Rey.

In Santa Monica, the steep coastal palisades--and a virtual lock on oceanfront land holdings--would ensure that only the Southern Pacific's trains could reach the harbor it envisioned at Port Los Angeles. The Southern Pacific's move, Robert Fogelson wrote in his 1967 history The Fragmented Metropolis, "was consistent with its determination to monopolize trade in southern California."

Suspicious of the Southern Pacific's intentions, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce fought back. "The Southern Pacific came here and had everybody for its friend," said real estate salesman Robert Widney (as quoted by Fogelson), "but we have learned that when they want anything badly our interest lies the other way."

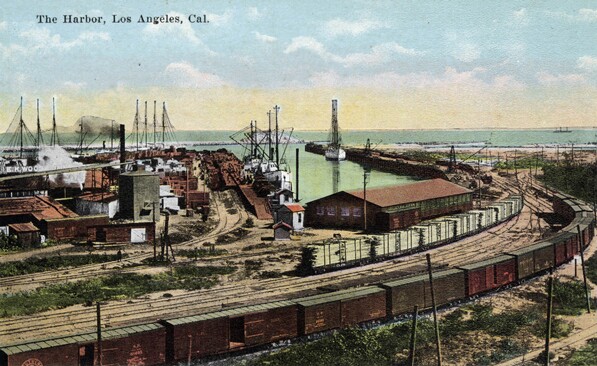

Both sides dug in, and a protracted political war, dubbed the Free Harbor Fight, ensued. It was not resolved until 1896, when Congress allowed the Army Corps of Engineers to choose the more suitable site for an artificial harbor. In 1897, the Corps opted for San Pedro Bay. Work began on the harbor two years later.

A new breakwater--along with subsequent improvements--transformed the area into a major commercial shipping centers. Today, the twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are the two busiest container ports in the United States. What was good for the commercial freight business was bad for tourism, however. In a sign of what might have happened to Santa Monica had the Southern Pacific prevailed, the exclusive Terminal Island resort of Brighton Beach became a fishing harbor after an 1916 dredging project altered the shape of the shoreline. Canneries replaced summer cottages.

Santa Monica's Port Los Angeles, meanwhile, closed to shipping in 1913, unable to compete with the improved harbor at San Pedro Bay. In 1920, the wharf was torn down, leaving little physical evidence of the Southern Pacific's bold plan to turn Santa Monica into a commercial harbor.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here will provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.