How Los Angeles Remembers: These Fading SoCal Landmarks Capture the Region's Nuanced History

Forgetting is famously what Los Angeles does best. Urban historian Norman Klein called it erasure — the active scrubbing away of what must not be remembered. Despite erasure, memories do have a place in Los Angeles. Some are official monuments. Some are in ruins and need critical excavation. Some require the imagination to be seen.

That's what I learned as a participant in a year-long examination of how Los Angeles remembers. I was part of former mayor Eric Garcetti's "Civic Memory Working Group" led by Christopher Hawthorne. The group's report — Past Due — lists 18 recommendations for maintaining the city's infrastructure of memories. One recommendation is an audit of existing memorials and monuments.

I have some suggestions for places of memory that might be included.

J. B. Lankershim: A Forgotten Monument

On a spit of land, hemmed in by multi-million-dollar houses, a stubby obelisk remembers one of the men who helped sell Los Angeles into existence at the end of the 19th century. Historic-Cultural Monument No. 181 honors James Boon Lankershim, developer of San Fernando Valley farmland when the Valley's wheat empire ended. Lankershim and his father, at various times, controlled 60,000 Valley acres.

J. B. subdivided more than 10,000 of them as farms sites beginning in 1887. Another 2,000 acres became home and business lots. That community, once called Lankershim, is now North Hollywood.

Anglo owners of former rancho land, like J. B., remade themselves in the 1890s as developers, financiers, politicians, and civic boosters. They made the Owens Valley a semi-desert to make the San Fernando Valley bloom with orchards of walnuts, oranges, and apricots. They platted suburbs that made turn-of-the-century Los Angeles a "white spot" of segregated housing.

In 1920, J. B. donated 20 acres of land overlooking Studio City to the Boy Scouts of America for a campground. When J. B. died in 1931, his will directed that his ashes "be spread over some portion of the lands in the San Fernando Valley" and that a monument be set up "on some part of the present holdings in the San Fernando Valley in the form of an obelisk." With the help of the scouts, the Lankershim monument was completed in 1938. J. B.'s ashes were scattered nearby.

The Boy Scouts sold the campground in the 1950s to a subdivider, reserving a narrow path from Nichols Canyon Road to the plot where the obelisk stands. It's reached by climbing a steep flight of ruined steps. The Lankershim monument is unmarked, apparently closed, and almost entirely forgotten.

Location:

34° 7.668′ north; 118° 21.922′ west, visible on Google Satellite View

Access:

There are no signs that indicate the entrance to the Lankershim monument at the end of Nichols Canyon Road where it intersects with Chandelle Road. The site seems to be closed.

Sources:

The Historical Marker Database summarizes the history and location of the Lankershim monument. Mary Mallory, writing for the Daily Mirror website in 2013, describes the Lankershim family's history.

El Aliso: The Loneliest Monument

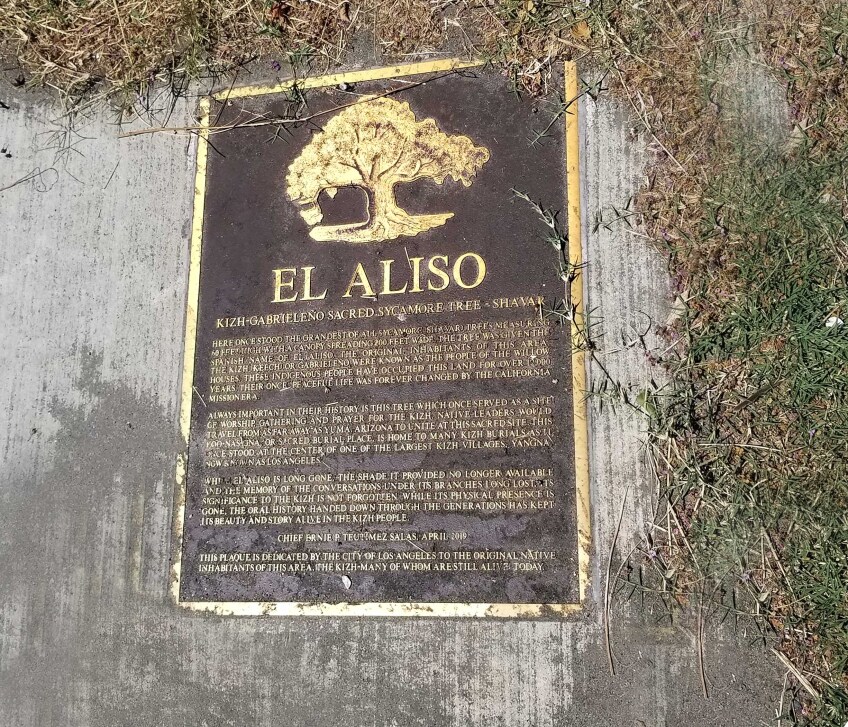

At the eastern edge of downtown Los Angeles, where Commercial and Vignes streets intersect, a bronze-colored plaque is set into the sidewalk. It's bordered by an empty lot and, across the street, a strip club. The plaque remembers what isn't there, illustrated by a relief of a wide-spreading tree. The plaque, laid down with modest ceremony in 2019, reads:

Kizh-Gabrieleño Sacred Sycamore Tree – Sha'Var

Here once stood the grandest of all sycamore (Sha'var) trees measuring 60 feet high with a canopy spreading 200 feet wide. The tree was given the Spanish name of El Aliso. The original inhabitants of this area, the Kizh (Keech) or Gabrieleño were known as the people of the willow houses. These Indigenous people have occupied this land for over 12,000 years. Their once peaceful life was forever changed by the California Mission era.

Always important in their history was this tree which once served as a site of worship, gathering and prayer for the Kizh. Native leaders would travel from as far away as Yuma, Arizona to unite at this sacred site. This Koo-nas-gna, or sacred burial place is home to many Kizh burials as it once stood at the center of one of the largest Kizh villages, Yaangna, now known as Los Angeles.

While El Aliso is long gone, the shade it provided no longer available and the memory of the conversations under its branches long lost, its significance to the Kizh is not forgotten. While its physical presence is gone, the oral history handed down through the generations has kept its beauty and story alive in the Kizh people.

— Chief Ernie P. Tautimez-Salas, April 2019

This plaque is dedicated by the City of Los Angeles to the original native inhabitants of this area, the Kizh, many of whom are still alive today.

If you're standing there, reading the plaque and imagining the tree where Los Angeles began, it's almost certain that you're the only visitor. The El Aliso plaque may be the loneliest place of civic memory in Los Angeles.

Location:

34° 03′ 10.6′′ north; 118° 13′ 58.2′′ west, shown on Google Street View

Access:

The El Aliso plaque is at 700 E. Commercial Street. On-street parking is nearby.

Sources:

Nathan Masters tells the tree's story in El Aliso: Ancient Sycamore Was Silent Witness to Four Centuries of L.A. History. The dedication of the El Aliso plaque is included in Paul Spitzzeri's A New Plaque for 'El Aliso' Sycamore Tree at the Homestead blog.

Madonna of the Trail: Monument to a Myth

As if striding south on Euclid Avenue in Upland, a 9-foot-tall icon of motherhood and Manifest Destiny carries a baby at her breast, ignores the toddler clinging to her apron, and holds a rifle at her side. She is armed, implacable and ostentatiously white.

There are 12 of these monuments — each a "Madonna of the Trail" — from Maryland to California along highways that had been the route of wagon trains in the 1840s and 1850s. The Daughters of the American Revolution put them up in the 1920s, a time when the Ku Klux Klan was again a political force in many states (including California) and when immigration from southern and eastern Europe was restricted and Asian immigration was prohibited.

Upland in the 1920s was part of the foothill citrus belt extending from Los Angeles to San Bernardino. Latinx workers in orchards and packing houses were strictly segregated, and union organizing was resisted with official violence.

Upland's "Madonna" affirms a national myth that a specific kind of American "conquered" the West. The "covered wagon days" celebrated on the statue's plinth, meant something else to Indigenous Californians, the state's Mexican landowners, and the migrants who labored in the vineyards of Los Angeles.

The monument was dedicated on a rainy Feb. 1, 1929 with a parade and a speech about Americanism.

Location:

34° 6′ 26.1′′ north; 117° 39′ 4.29′′ west, shown on Google Street View

Access:

The monument is at the south end of the Euclid Avenue bridal path at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Foothill Boulevard. On-street parking is limited.

Sources:

The YouTube channel Sidetrack Adventures visited the site of the Upland "madonna" and summarized its history. Inland Living magazine (February-March 2011) highlighted the monument. Art in Public Spaces has additional photographs.

The Round House: A Lost Monument

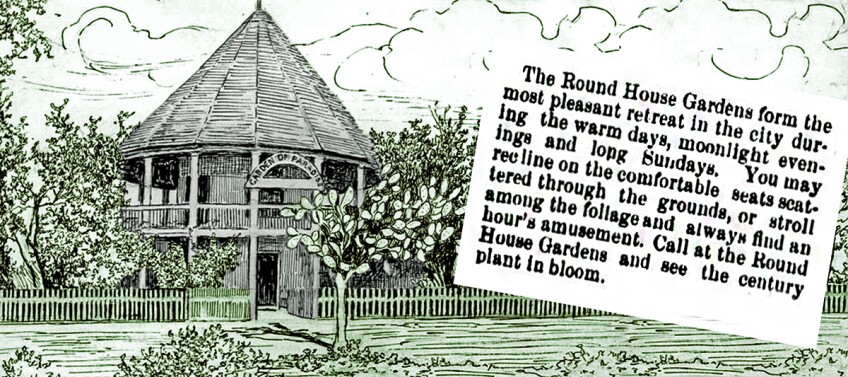

Odd architecture is supposed to be characteristic of Los Angeles, and it appears surprisingly early. Sometime before 1850, an ex-sailor built a house on Main Street between 3rd and 4th. Unlike the typical adobe house of the period — one or two rectangular boxes — this house was cylindrical and two stories tall. It was topped by a conical roof of shingles over rafters that extended several feet. The house looked like a silo with a wooden wizard's hat.

The ex-sailor appears to have been bankrupted by a building that every Angeleno called the Round House. George Lehman bought it in 1855 or 1856. His purchase turned Lehman into Round House George for a generation of Angelenos.

He spent two years improving the grounds, planting fruit trees and rose bushes, setting out hedges of cactus on Main and Spring streets, and creating bowers along meandering paths. He renamed his creation the Garden of Paradise (although it was really a beer garden). He thought his paradise needed Adam and Eve and a supporting cast of other biblical figures. Lehman had them cast in concrete and whitewashed to look like marble. The serpent was there too, lounging on the branches of an orange tree that stood in for the Tree of the Knowledge. Not everyone was impressed by the architecture. The Los Angeles Star in 1857 called the building an "uncouth pile."

When business declined in the late 1870s, Lehman rented the house and grounds to Caroline Severance — notable abolitionist, suffragist and feminist — who opened the city's first kindergarten on the ground floor. In 1879, Lehman was forced to sell all his properties. The Round House became a tenement and later a flop house for transient workers.

An eccentric landmark, the city's first theme park, and a pioneering educational experiment, but the Round House isn't remembered by a monument. A few photographs and newspaper clippings remain. But the Round House isn't really lost. Having escaped an official interpretation, it now belongs entirely to our imagination.

Location:

Street widening in the 20th century obscures the precise location of the Round House. The site at Main and 3rd streets is now the Ronald Reagan State Office Building.

Access:

The Los Angeles Public Library's online collection holds three photographs, including one taken when the site was the Garden of Paradise. Photographs of the garden's cactus fences showed 19th century Americans an exotic Los Angeles. These images can be found through the Calisphere archive network.

Sources:

The story of the Round House and its evolution from beer garden to kindergarten is told in Odd House at Lost LA and by Nathan Masters at Los Angeles Magazine.

Places of Memory

Los Angeles does remember, if fitfully. Forgotten monuments—like J. B. Lankershim's—invite excavations in the past to restore them to remembrance. Monuments that manifest the past's exclusive control over who will be remembered—like the Madonna of Upland—need the company of inclusive monuments of who we have been and who we are today. The erased monuments of Los Angeles—like the Round House and the El Aliso tree—set the imagination free to situate them in the place where they are no longer missing.

Encounters with monuments stir up narratives and counter narratives, evoking the stories in the landscape and inscribing them in memory.