How Did the Mexican-American War in California Actually End? A Table, Cahuenga, and Historical Uncertainty

It’s a perfectly ordinary table, big enough for two to sit across from each other. The grain of the wood shows through the worn finish in places. The panels of the top are uneven, but not so much to make the table unusable.

It’s a piece of homely furniture that could have been found in any kitchen anywhere in Los Angeles until the middle of the 20th century. A table like it might be in anyone’s garage today, after losing its one drawer, and now a place to set a clothes hamper or store garden tools

Except this ordinary table isn’t in a garage. It’s in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. It stands, elevated and lighted in a tall glass box, as a witness to history (although both the witness and the history, in this case, are somewhat ambiguous).

The exhibition "Becoming Los Angeles" regards the table as so significant that it’s one of the “touchdown” points visually linked to other key objects in the exhibition by the swooping overhead ribbon that symbolizes the flow of time.

If we imagine time that way, as a flow that condenses in a place to make history, then a single hour in the 1.5-million-hours of this table gave it significance. Time is supposed to have touched down on its well-used top on the morning of Jan. 13, 1847, as the table sat on the porch of an adobe house in a pasture called Campo de Cahuenga (or Cauenga). The Campo de Cahuenga is Universal City today.

The Mexican American War of 1846-1848, the museum says, ended in California on this tabletop on that January morning. Given the realities of rural life in Southern California in the 1840s, the table would probably have been the best available in a house that, according to many accounts, belonged to Tomás Féliz, a rancher, on the day the war ended.

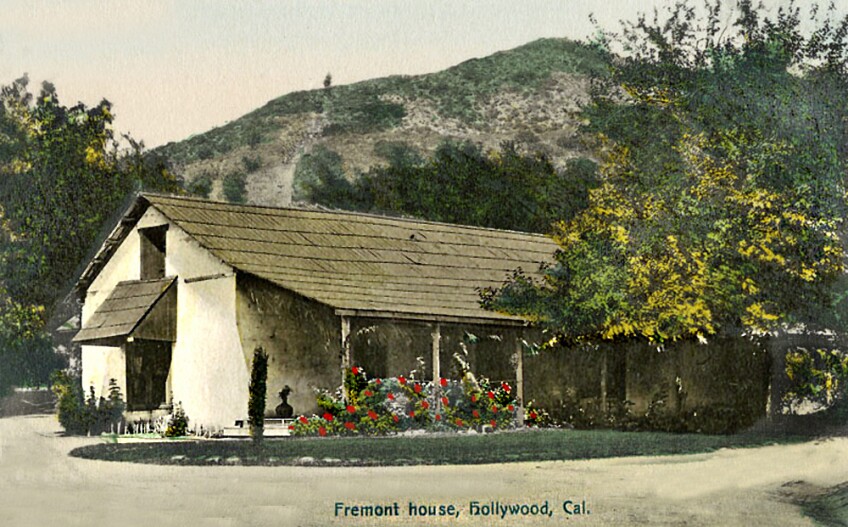

The table was positioned – ceremoniously? anxiously? without much thought? – on the long porch in front of the house in anticipation of a meeting between the commanders of the approaching American forces and the embattled Californians. (In a hand-colored postcard from 50 years after, a shingled roof shades the porch of a building that the Los Angeles Public Library identifies as this house. The building is the sort of adobe rectangle from which so many Southern California tract houses were derived, thanks to Cliff May.)

The United States and Mexico (of which California was a fractious part) had been at war since the previous May. Los Angeles, the sometime capital of the Mexican state, had been taken by the Americans and then lost the previous year. Several battles, small but some of them bloody, had since been fought.

Jan. 13, 1847, was a Wednesday. The day was rainy. The houses of colonial California, with few windows, were notoriously dark. The porch would have been the best location for any business that required, for example, writing out a formal document.

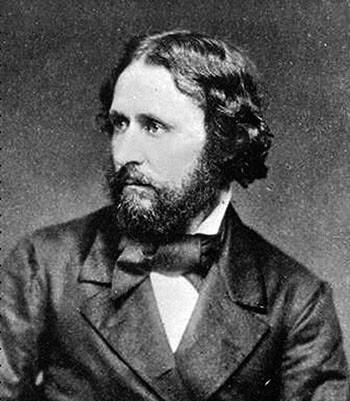

The table on the porch on that Wednesday morning is in the foreground of the events that required enough light. In Hugo Ballin’s 1931 mural (still mounted in the lobby of the Guarantee Trust Building at 5th and Hill streets), General Andrés Pico, commanding the Mexican forces in California, is shown seated at the table. Behind him are members of his staff. Leaning over Pico, who is shown in typical Californio costume, is U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont. Frémont is in full uniform.

Frémont wasn’t the most senior American officer bringing the war to Southern California in 1847. (General Stephen Watts Kearney and Commodore Robert Stockton jointly commanded.) But Frémont was the most impetuous. In Ballin’s mural, Frémont is pointing out something on the sheet of paper on the table. Insistently? Helpfully? Arrogantly? The paper Pico is about to sign is the surrender of the Californian forces.

The Mexican American War in California was fought, on the American side, by a mixed force of soldiers, sailors, marines, and volunteers from among American immigrants. They had confronted a local militia of Angeleño and Sandieguino horsemen in three engagements in Southern California since the beginning of December 1846: the Battle of San Pasqual (Dec. 6-7), the Battle of Rio San Gabriel (Jan. 8), and the Battle of La Mesa (Jan. 9). San Pasqual was dominated by the Californians. (Stockton described San Pasqual as “Kearny’s defeat.”) Rio San Gabriel and La Mesa were skirmishes that the Americans dominated, although the Californians had shown that they would fight.

But they couldn’t win. On Jan. 10, as the Californians sought an end to the conflict, American troops re-entered Los Angeles without resistance.

Even before he sat down with Frémont three days later, Pico was prepared, on behalf of the government of California, to end hostilities and permit California to be handed over to the invading Americans. He anticipated that treating with Frémont, not Kearney or Stockton would turn out to serve both his and Frémont’s interests.

Sitting across from each other (if they in fact did sit together), Frémont and Pico, for different but complimentary reasons, wanted the Mexican-American War to end in California on that Wednesday morning. Pico wanted peace on terms that weren’t punitive; he expected to be imprisoned, perhaps shot, if captured by Stockton or Kearny. Frémont wanted publicity; he intended to have a political career and perhaps be president one day.

Frémont’s decision to sit down with Pico, between them a generously worded agreement waiting to be signed, would eventually mean that Frémont would be remembered as the man who ended the Mexican-American War in California. (Kearney, Frémont’s superior, bitterly complained later that he had led the Americans to victory, not Frémont.)

Other memories of January 1847 are just as contentious. In illustrations of the scene around the small, wooden table (that most sources say belonged to Tomás Féliz), Frémont is always in uniform. Sometimes Pico is uniformed as well, sometimes not. The house itself, substantial in Ballin’s mural, is cruder, even rundown, in other illustrations. It’s never raining in any of them. Perhaps it wasn’t raining.

Edwin Bryant, a lieutenant in Frémont's battalion, didn’t mention rain in his account of the meeting between Pico and Frémont, published a year later. Bryant wrote that it rained heavily the day after as Frémont and his troops entered Los Angeles. It may be that the two events have been conflated.

It isn’t only the rain that appears and disappears from the morning of January 13. The house where Pico and Frémont met probably didn’t belong to Tomás Féliz, who had died in 1830. (And Féliz, whose table this may or may not have been, is sometimes Félix or Felez in published accounts or not mentioned at all.) According to archival research in 2000 for the Metro Red Line subway extension, the house was the property of Eulogio de Célis, who had purchased the Campo de Cahuenga and the surrounding Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando from Pío Pico, Andrés’ older brother, less than a year before the meeting on the porch.

[view:kl_discussion_promote==]

According to some accounts, but neither Bryant’s nor Frémont's, Andrés Pico, who never grew proficient in English, directed Captain José Antonio Carrillo, acting as a commissioner for Mexico, to write out, in both Spanish and English, the terms for the cessation of hostilities. In the illustrations, you never see the bilingual Carrillo at work. (Jessie Frémont noted, in an 1895 account of the events of 1847, that her husband “knew Spanish well” and did not need an interpreter.)

The agreement has been called the Treaty of Cahuenga, although historians usually title it the Capitulation of Cahuenga. Perhaps in the illustrations, “capitulation” is rendered by the image of Pico dressed in the everyday outfit of a caballero, with Frémont in uniform, and “treaty” when Pico is dressed in the uniform of a Mexican general. (Bryant noted that both the officers and men of Frémont’s “small army” wore buckskins “smeared with mud and dust” on their way from the Campo de Cahuenga the following day, although Frémont might have dressed more formally for the Wednesday morning meeting.)

Pico signed the treaty/capitulation as the Californians’ battalion commander and “head of all the national forces in California.” Pico is sometimes described as California’s governor in accounts of the meeting. Pio Pico, the governor in fact, had left for Mexico the previous August to raise support for the defense of California. And José María Flores, the commander of the “national forces” had turned them over to Pico on January 11 before Flores left California for Sonora. Andrés Pico, both politically and militarily, had been left with the necessity of sitting at a small, wooden table on the porch of an empty ranch house to surrender California to an impetuous, junior officer of the American Army.

It’s unlikely that Eulogio de Célis or Pio Pico (or Andrés Pico, who had leased the rancho for a time) ever lived there. The building was probably built for the Mission San Fernando Rey de España around 1811. But it might have been built in either 1783 or 1795 for Mariano de la Luz Verdugo, who had been granted grazing rights to the land around the Campo de Cahuenga before the land, at the insistence of the mission fathers, was transferred to them.

The house has been described as abandoned on that January Wednesday. Lieutenant Bryant wrote that it was deserted, which is not exactly the same thing, particularly when armies are expected. Deserted out of fear or abandoned by an indifferent owner or just temporarily unoccupied, the house might have held a table and chairs that could have been brought out beneath the overhanging roof that may not have been dripping rain.

The building was demolished around 1900, but much of its foundation and flooring was excavated between 1995 and 1998 during construction of the Red Line subway. The archeological survey of the site found both European and Native American artifacts at the site suggestive of daily life in the first half of the 19th century. Reburied to preserve them, the ruins of the house were overlaid by a replica, and Metro provided the imitation ruins with interpretive signage.

Perhaps the abandoned/deserted/unoccupied house was lived in, and Bryant mistook the typically sparse household arrangements of rural Los Angeles as evidence of that the house had been discarded. Perhaps the house had only been left untenanted when Los Angeles was first captured by the Americans in August 1846. The presence of one small table can’t tell us one way or the other. It seems unlikely, though, that a well-made table, like the one in the museum exhibition, with its planed top and turned legs, would have been left behind in an abandoned house.

There is another story submerged in the story of the rainy/not so rainy Wednesday on the porch of the house where General Andrés Pico in uniform/in nondescript attire did nor did not sit together with Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont (presumably in uniform) to read and sign, along with members of his military staff and Frémont’s, the formal agreement that ended the war in California. (Frémont, needing something grander than a ceasefire agreement, called it a treaty in his report to Kearny and Stockton.)

The half-buried story is in Frémont’s memoirs (published in 1887), and it begins with a half-remembered name: Bernarda or, because Frémont isn’t clear, perhaps it was Maria Bernarda. The rest of the name was supplied by a telegram from José de Jésus Pico (a cousin of Pio and Andrés Pico who was there). The name Frémont couldn’t recall, the name José de Jésus Pico provided, was Doña Maria Bernarda Ruiz de Rodriguez.

José de Jésus Pico had a good reason to remember Bernarda Ruiz’s name, apart from her status as a respected widow and businesswomen in Santa Barbara whose mail service to Mexico, conducted by her four grown sons, Pico might have used. Pico had been arrested in San Luis Obispo on Dec. 14 by Frémont, summarily tried two days later, and convicted of violating his parole in rejoining the Californian forces opposing the Americans. Sentenced to be shot – the soldiers were already in formation to carry out the order – José de Jésus Pico pleaded for clemency, aided, Frémont later wrote, by the tears of his wife and his children. Moved, Frémont suspended the order.

(Frémont’s compassion went only so far. A Native American – one account calls him Pico’s “servant” – taken prisoner on Dec. 13 and accused of spying for the Californians, was summarily executed in front of the native families living in a native village near the former Mission San Miguel not far from Paso Robles.)

Pico attached himself to Frémont’s staff and followed him south to Santa Barbara – out of gratitude, Frémont believed, but perhaps, as an ardent Californian who had violated his parole and twice risked his life in defense of his home, Pico intended to influence what would happen next. At the very least, he might warn his Pico cousin Andrés if Frémont intended to be as belligerent as the Californians feared.

José de Jésus Pico, who knew Ruiz through family connections (and who may have sought her out for the purpose), brought Ruiz to meet with Frémont while he rested his troops at Santa Barbara in the week after Christmas. Frémont’s memoirs gloss over the details of their meeting, only complimenting Ruiz on her “sound reasoning” in wanting the war in California to end on magnanimous terms and encouraging her to be an advocate of peace among the Californians she knew. (Jesse Frémont’s account suggests that Ruiz also offered more, to get word of Frémont’s conciliatory attitude to Andrés Pico, but Jesse Frémont provides no details, and Frémont makes no further mention of Ruiz after their meeting in Santa Barbara.)

Some accounts have her appeals to Frémont motivated by concern for her four sons, then among the Californians opposing the Americans. Some have Ruiz anxious to retrieve horses that Frémont had commandeered from her corrals. (Frémont apparently did send them back.)

Some accounts credit Ruiz with brokering the treaty/capitulation that Andrés Pico and Frémont signed on January 13. Some accounts have her delivering a well-rehearsed outline of peace terms to Frémont during a two-hour conference in Santa Barbara. (Frémont doesn’t record the time in his memoirs.) A few accounts – are they plausible? – have Ruiz riding with José de Jésus Pico and Frémont to the Campo de Cahuenga to witness the signing of a document she had seemingly dictated to Frémont (or perhaps to Carrillo), the terms of which she had already personally communicated to Andrés Pico.

Bernarda Ruiz seems to be everywhere and then nowhere.

On Tuesday morning, January 12, Frémont met with Francisco Rico and Francisco de la Guerra, representatives from Andrés Pico. The meeting continued into the afternoon. Neither Ruiz nor Carrillo is present in Frémont’s and Bryant’s accounts. When Rico and de la Guerra left Frémont’s camp, the final terms were not yet concluded, according to Bryant. Other accounts have the entire document being written out that evening.

But perhaps the terms were still to be decided when Frémont rode from his camp the following morning to meet with Andrés Pico. Frémont, perhaps to magnify his own role, said that he arrived at the Campo de Cahuenga on the morning of January 13 alone (except for the vigilant, helpful José de Jésus Pico.)

Bernarda’s place around the table isn’t mentioned in Frémont’s memoirs (even her name was missing until José de Jésus Pico supplied it almost 40 years later). In illustrations of the events on the porch, Bernarda is never depicted (although a mural of the scene painted in 1951 for the Campo de Cahuenga Memorial Association shows a crowd of onlookers that includes the figure of a woman).

Had the terms already been concluded with the commissioners that Pico sent the day before, and the signing a brief formality? Were there any negotiations at all, apart from technical details, the agreement having been concluded in principle three weeks before in Santa Barbara and accepted by Andrés Pico, his agreement passed through the network of related Californians who seem, in all these accounts, to be always at hand? Was the agreement already written out in English, ready for Carrillo’s’ translation as he sat at the table under the sloping roof of a house that some say belonged to the long-dead Tomás Féliz, some to his widow, others to Eulogio de Célis, and some say was abandoned?

What if the operatic qualities of these events – armies marching, noble women pleading, lonely rides to fateful meetings, solemn officers standing around in colorful uniforms – were something else, something designed to be a usable history and not what the meeting on the porch was in fact?

At some point on Jan. 13, 1847, the American and Californian signatories (who seem to appear out of nowhere) sat at the table to make the treaty/capitulation official. The American signers were P. B. Reading, Major; William H. Russell, Ordnance Officer; Louis McLane, Jr., Commanding Officer, Artillery, all from the California Battalion. The Californians were José Antonio Carrillo, Commandante de Esquadron, and Agustin Olvera, Diputado (Deputy of the Californian Assembly). Both Frémont and Andrés Pico signed their approvals below the signatures of the five commissioners.

Like much of written history, the accounts of the meeting between Pico and Frémont are either sketchy, romanticized, or only seem to be authentic because the account includes plausible details, like the rain or Bernarda’s meeting with Frémont or Carrillo writing out the agreement. (The copy that Frémont forwarded to Stockton that night, according to one scholarly analysis, bears the handwriting of Theodore Talbot, an artillery lieutenant in Frémont’s brigade, and the signatures of the commissioners, Frémont, and Pico. Talbot, in his letters home, does not place himself around the increasingly crowded table at the Campo de Cahuenga that Frémont said he went to alone, except for José de Jésus Pico, who seems to have quickly gone from rebel to Frémont’s loyal retainer.)

The tableau of figures around the table is blurry. Who they are shifts from account to account, illustration to illustration. Fresh memories of Jan. 13, 1847 (Bryant’s, Talbot’s) and memories nearly 40 years old (Frémont’s, a few others) align only partially with the details in secondary narratives, which begin as soon as the Mexican-American War ends. Something happened that morning at the Campo de Cahuenga. A war (widely considered unjust then and now) ended, in California at least, on honorable terms, something worth holding on to, even though we can’t assign a definitive role to every person who may have caused history to touch down at a deserted/unoccupied/abandoned house that also happened to hold a well-made, but ordinary, wooden table at which a document essential to the history of California and the West could be negotiated (perhaps), written out (by someone), and signed.

And although the table in the case at the museum is one of the few things that bears witness to such facts that we can accept, we can’t even be assured that this table – the one in the Natural History Museum – is the relic of history we want it to be.

The museum believes that its table (a loan from the Charles J. Prudhomme collection in the museum’s Seaver Center for Western History Research) was made in 1844 by Charles Burroughs and used for the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847 at the ranch of María Jesús Lopez de Féliz, the widow of Tomás Féliz (and married since 1835, other another source says, to Jordan Pacheco).

Leonard Pitt (historian) and Edna E. Kimbro (architectural conservator and historian), who researched the Campo de Cahuenga site as part of its historical and archeological investigation for the Metro Red Line subway in 2000, discounted any Féliz connections to the treaty/capitulation, the house, and the table. They wrote:

In 1916 … Zaragosa Lopez de Briton presented to the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History a table that she asserted was made in 1844 by Carlos Barros (also known as Charles Burroughs) and used for the signing of the treaty. There is no corroborating proof of this and since the rancho was said to be in deserted condition, it seems implausible, especially since the same claim has been made for another table in the possession of the Campo de Cahuenga Historical Memorial Association.

After signing the agreement, Pico turned over to Frémont the two cannons the Californians had captured from Kearny at San Pasqual (Bryant said only one was returned). In some later accounts, after Frémont and his troops entered the recently recaptured Los Angeles, the demobilized Californians threw a grand ball at the home of Alexander Bell which Frémont, Kearny, and Stockton attended as honored guests (although the three men were constantly at odds, a conflict that would lead to Frémont’s conviction for insubordination at his court-martial in 1848).

The Californians and the American commanders may have danced that night with the wives of the Californians they had lately been fighting, but Bryant, writing a year after the signing of the treaty/capitulation, said that he found Los Angeles mostly deserted on Jan. 14. None of the pretty girls he had been told were there could be found.

An aging and somewhat forlorn Frémont returned to the Campo de Cahuenga in 1877 to identify the site of his meeting with Andrés Pico. He found the house in ruins, despite the postcards and photographs that show it still standing, with roses blooming at the edge of the famous porch, and waiting, it would seem from other accounts to be demolished again by 1900.

Perhaps history isn’t a ribbon unrolling overhead that touches down on a definite table top, rendering one of those still, silent things, generally overlooked, into a relic of time. Perhaps history is only the stories we tell.