How Catalina Evaded the Conquest

“On a clear day, you can see Catalina.” From noir femme fatales to juice-cleansing hikers, the phrase has been echoed by Angelenos for decades, if not centuries.

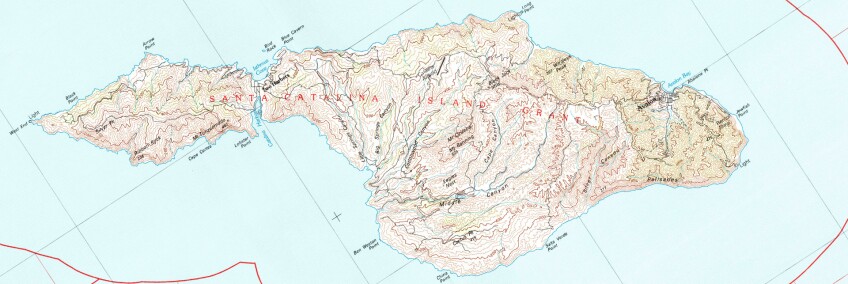

Los Angeles’ citizens use Santa Catalina Island as a smog barometer, but few know how its pristine natural beauty abided against all odds. Mainland California endured ravages at the hands of those attempting to manifest their own destinies – whether through oil, gold, or fame. Catalina passed through the same phases as the mainland: Indian, Spanish, Mexican, American. It played host to explorers, hunters, miners, ranchers, rancheros, real estate seekers, fishers, soldiers, and yachters. And yet, while the businesses of real estate development and natural resources extraction marred so much of the mainland’s natural beauty, Catalina emerged virtually unscathed.

Charles Frederick Holder, author and co-founder of the Tuna Club, described his approach to the island in a passage that is as accurate now as when Holder wrote it 105 years ago.

We are very near it now, sailing due south down the channel…Watch the cliffs, how boldly they breast the sea, rising like the grim giants hundreds of feet in air, with thick beards of waving kelp at their base. Great slopes of green stretch away; then a glimpse of white beaches, of breaking waves gnawing at submerged rock; a flash of flying-fish wings; cañons—rivers of verdure—winding their way skyward; and, far away, the tops of the high mountains of Cabrillo, about whose crests float flecks of cloud in the drowsy air…

So how did the island shelter itself from destruction? In that oldest of California customs: a combination of luck and fate.

Californios, Smugglers, and the End of Mexican California

When Mexico won its war against Spain, it levied a near-100-percent duty on foreign goods, and smugglers discovered the island. Spanish, French, Russian, English, American, and South American merchants, traders from New England and the Sandwich Islands, men hauling goods from China and even pirates all dropped anchor in Isthmus Cove or Cat Harbor. Under cover of darkness, they unloaded some two-thirds of their wares in caves or buried them in the sand. After sailing on to check in with Mexican customs and pay the tariffs on their lighter loads, they would then return to Catalina, re-load their ships and sail up and down to coast, selling goods to complacent Mexicans and rancheros. In order to maintain the secret outpost, a collective hush fell over the island.

That silence was finally broken by an American ship captain named Thomas Robbins who asked for the island and was granted it as a personal favor from Pío Pico in one of Pico’s last acts as governor of Mexican California. Thus began a long succession of private owners.

Civil War and Gold Diggers

In 1863-64, around the time real estate investor James Lick – owner of Rancho Los Feliz and proprietor of San Francisco’s Lick House hotel – purchased the island, gold was discovered on Catalina. Lick attempted to keep squatters at bay, but to no avail. Mining shafts (which can still be seen today) shot through July Valley and Cherry Valley. Lick was fighting a losing battle, until a greater battle won out.

The Civil War then gripped the United States, and many residents of Los Angeles sympathized with the Confederacy. The federal government became paranoid that Confederate privateers would use the island as a meeting place. In 1864 it issued an evacuation order for the island and built a military barracks, still visible today, at the isthmus. So, unlike the rest of the Golden State, prospectors had only one year to plunder Catalina.

After the war, Lick determined to realize the island’s financial potential once and for all. He used the gold-diggers’ shafts to claim the existence of silver, lead, and zinc deposits and enlisted Anaheim’s first mayor, Major Max Strobel, to sell the island to an English syndicate with plans to mine the whole of the island. Catalina, it seemed, would finally suffer the same ore mining wreaked upon so many of California’s mountains.

Strobel sailed to London to close the deal with the syndicate and collect the price of 200,000 pounds. However, he never appeared at the meeting; instead, he was discovered dead in his hotel room that morning. The cause of death was unknown.

Strobel’s failed mission recalled an earlier attempt to rob the island of its riches. In 1828 a pioneer named Samuel Prentiss found himself shipwrecked near San Pedro. Dazed and confused, Prentiss walked to the San Gabriel mission, where he was told by one of the Tongva people that a mound of Indian treasure and pirate plunder was buried under a tree on the island. He drew up a map and caught a boat, but on his voyage a strong wind caught the vessel and the map fluttered overboard. He never found the loot.

World War and Fishing Freaks

At the turn of the century, Catalina changed hands once again and, with the building of the town of Avalon and the Hotel Metropole, California high society came together to fish for sport.

Unsustainable fishing has long been a problem on the West Coast, one with origins that predate legal environmental standards. Charles Frederick Holder, a passionate naturalist, witnessed the wanton waste of life with the fishing freaks and realized that no island, however bountiful, could forever sustain such human gluttony and greed. Overfishing would be bad for the tourism business, so he and his associates established the Tuna Club in 1898. According to Tuna Club historian Michael Farrior, “Holder established strict angling rules designed to give the fish what he considered an even chance for its life. The logic behind this being that far fewer fish could be taken with rod and reel than by handlines, therefore protecting the resources. Soon anglers and boatmen alike endorsed the club's motto of ‘Fair play for game fishes.’”

Whereas clubs of the east, and even the California Club were based on a person’s social standing, to become a member of Catalina’s Tuna Club one had to catch “a Tuna weighing 100 pounds or over, or a Swordfish or Marlin Swordfish weighing 200 pounds or over on regulation tackle...” The Club soon had members of such esteem as conservationist and president Theodore Roosevelt. Hollywood people like Cecil B. DeMille, Hal Roach, Joseph Jefferson, Stan Laurel, Jackie Coogan, and Charlie Chaplin also joined, and visitors like Winston Churchill graced the little club. The British prime minister reportedly caught a 188 pound marlin in twenty minutes (a feat that generally took between three and four hours), and spent the rest of the day in the club’s lunch room asking club members why they made such a fuss.

Tourism continued to boom but, amusingly enough, the island’s owners would not allow liquor at their glamorous getaway. One enterprising boater anchored between Sugar Loaf point and the hotel with signs reading “Hardware on Ice, Boats to Let, Etc.” and stocked his hull with “Etc.” – hard liquor for swimmers and fellow boatmen alike. More and more visitors and residents came to Catalina until the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941.

Two weeks later, the Coast Guard canceled regularly scheduled passenger steamships to the island. In secret at Toyon Bay, the Office of Strategic Service (forerunner to the CIA) set up a base for expert training with weapons and explosives, martial arts, hand-to-hand combat, survival skills, map reading, cryptography, radio operations, and covert operations. Many of the men at Toyon Bay were of Hawaiian or Japanese descent and would be sent to Burma or China to gather intelligence behind enemy lines. They began training a year after Executive Order 9066 signed Japanese Americans into internment camps.

The war ended in 1945, and tourism slowly returned. But the unabated energy of young people in the 1930s gave way to the loss and suffering that disillusioned them. After the war, people just didn’t feel like doing the jitterbug. The 1950s were about to take hold of California. Both McCarthyism and the automobile craze would keep the island paradise sequestered from the ills that plagued mainland California in 1950s. The steamer dock at Avalon pier was taken apart during the 1960s, and replaced by facilities meant to dock various private boats.

The latest in the long line of Catalina’s owners, Philip K. Wrigley, had taken over stewardship of the island from his chewing gum magnate father. Wrigley had the good sense and common decency to hand over 42,135 acres of the island to the Catalina Island Conservancy, a nonprofit he established in 1972. It protects the island’s plant and animal life to this day.

The vivid past of the island has settled back into its dusty cliffs, and Catalina awakes as if from a dream to discover itself exactly as it was before it all began. So how did the island shelter itself from destruction? One might say a war, smugglers, another war, an untimely death, a society club, a third war – or a gust of wind.

And indeed, Holder continues his description:

…there is something in the soft wind that speaks of contentment and rest. A butterfly drifts aboard and inspects us one by one—a messenger from the Isle of Summer. We pass a pinnacle of rock, and, on a sea of glass, glide into the little bay, with its perfect crescent beach, its pavilion and hotels, climbing streets and long rows of shops and homes, beyond which the deep cañon winds up to distant mountains that overlook the Western sea.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Dec. 23, 2016, with added details about the island's post-WWII years and corrected information about the Wrigley family's creation of the Catalina Island Conservancy.

Further Reading

Barnard, Charles N. "On Santa Catalina Island, the Kings of Swing Held Sway." The Smithsonian (1994): 153-67. Print.

Farrior, Michael. "History of the Tuna Club." Catalina Island - Hotels, Tours, Boats, Dining. Web.

Holder, Charles F. The Channel Islands of California. Chicago: A. C. McClurg and, 1910. Print.

Pedersen, Jeannine L. Images of America: Catalina Island. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2004. Print.

Robinson, W. W. The Island of Santa Catalina. Los Angeles: Title Guarantee and Trust, 1941. Print.

Smith, Jack. "Wings Across the Water : At the Turn of the Century, the Fastest Way to Get a Letter to Catalina Was by Carrier Pigeon." Los Angeles Times. 23 Feb. 1986. Web.