How a Health Guru Helped L.A. Discover its Hiking Trails

Long before yoga pants made their first appearance in Runyon Canyon, a health guru helped Angelenos discover their local mountain trails.

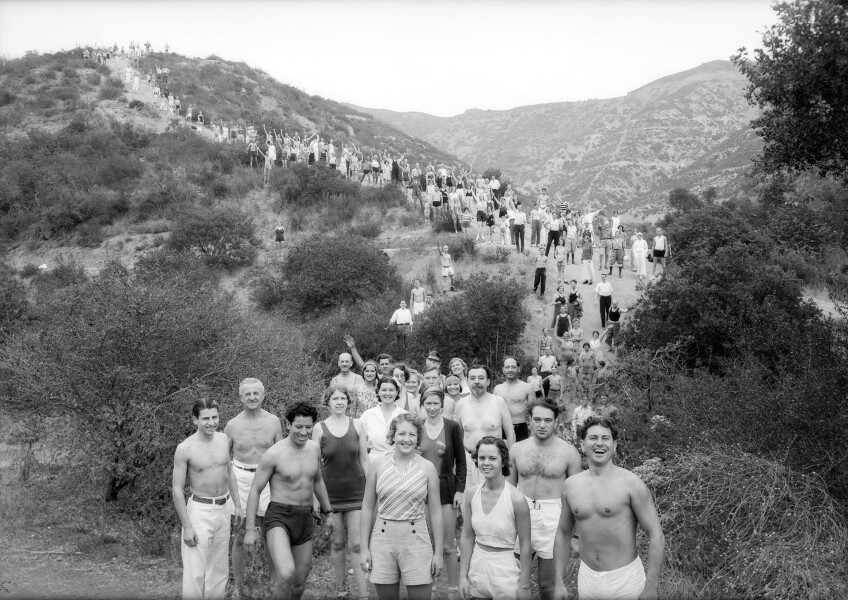

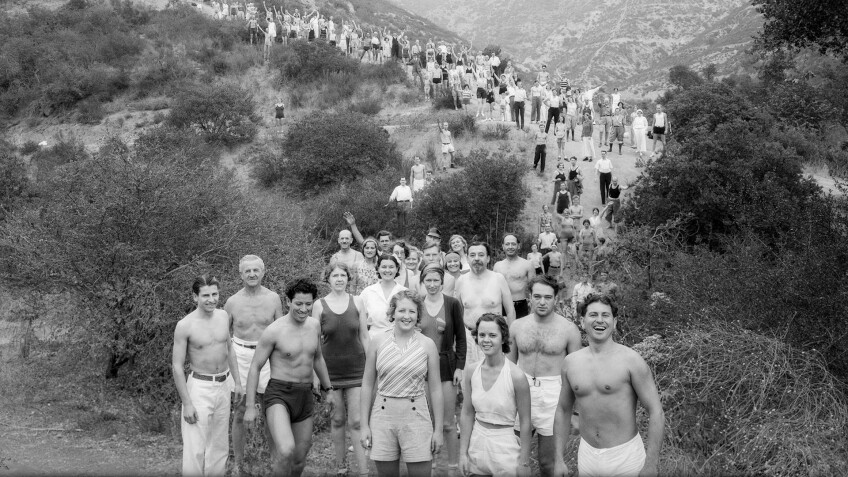

Beginning in 1924, on the first and third Sunday of each month, members of the Wanderlusters Hiking Club followed Paul C. Bragg into the hilly terrain around Los Angeles. Dozens of them traipsed through Altadena's Millard Canyon or hiked up Griffith Park's Mount Hollywood. Men doffed their shirts. Women wore bathing suits. Sunscreen had yet to be invented.

Their sprightly leader had moved to Los Angeles in 1921 and set up what he claimed to be the nation's first health food store on Seventh Street, just west of Figueroa. In his paid "Health Hints" column in the Times, Bragg advertised services like his Hydralite Bloodwash Bath, a hot-water shower that lasted for several hours, and products like Live Sprinkle, a salt substitute. His dietary recommendations ranged from prunes and whole wheat bread to Knudsen's Velvet cottage cheese ("it melts in your mouth") and Fig-Co, a coffee substitute made from figs and barley.

Los Angeles, a city that then buzzed with the fervor of a hundred cults and religious revivals, embraced Bragg's food fanaticism -- and arguably still does today.

Outside Los Angeles, Bragg was a controversial figure. In 1930, the postal service debarred the self-styled "professor" from the mails, alleging fraud. The American Medical Association denounced him as a "food faddist." He likely overstated his age by 14 years to bolster his claims of longevity.

But in Los Angeles, for a time, he championed what he billed as the city's "return to Nature."

In fact, hiking was nothing new in the Southland. Bragg's innovation, rather, was to sell it as a fitness activity: "Hiking is a wonderful sport to keep you young and fit and recharge your physical battery from the sun's rays."

His enthusiasm perhaps blinded him to the dangers of sunburn or heat stroke. "Perspiration is one of nature's greatest blood-purifying methods," he once wrote in his column. "Summer, then, is the best time to exercise for bodily health. Don't say it's too hot to exercise. A good 'sweat' actually cools you off."

But the images here -- commissioned by Bragg in the 1930s and recently digitized by the USC Libraries with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities -- reveal a man unable to conceal his affection for Los Angeles and its trails.

"There is a veritable Paradise in the mountains lying adjacent to Los Angeles," Bragg wrote in another of his columns, "and yet few people avail themselves of the opportunity to frolic in the sunshine."