Horrible Catastrophe! Disaster in Civil-War-Era Los Angeles

On a blustery Monday afternoon in the spring of 1863, a small, steam-powered tender passed down the tidal creek that led from New San Pedro[i] to the deepwater anchorage where the side-wheel steamship Senator waited. Earlier that afternoon, the Senator had received a consignment of freight from the tender. Now the Ada Hancock was returning with passengers bound for San Francisco. The little vessel was crowded with 50 or more adults and children.

Albert Sidney Johnston, Jr., the 17-year-old son of Confederate General A. S. Johnston, was on board, perhaps considering if he would join the war that had killed his father the year before.[ii] Louis Schlesinger,[iii] a Los Angeles merchant, had business interests that required the three-day trip to San Francisco as did Maximilian Strobel, one of the founders of the Anaheim colony.

Hiram Kimball and Thomas Atkinson, Mormon missionaries, were on their way from Salt Lake City to Hawai’i. Lumberman William Waddell was returning home to Santa Cruz. Henry Oliver was returning to San Francisco with stock certificates and documents connected to his Arizona mining investments.

Fred Kerlin, employed at the Tejon Reservation, carried $30,000 in paper currency. William Ritchie, a messenger for Well Fargo & Company, watched over a strongbox with $11,000 in gold dust from the Arizona mines and $575 in coins and bank notes.

William Pratt and Richard Price, both later described as “colored,” were on the Ada Hancock, along with men even more anonymous:[iv] Gardiner, Sweeney, Levi, Hubbard, Joe (a “colored” servant) and a Sonoran and a teamster (names unknown).

Jovial, popular Thomas Seeley, captain of the Senator, was on board the tender. He had a practice of leaving his ship at Los Angeles under the command of First Mate J. S. Butters, who continued to San Diego while Seeley played cards in the barroom of the Bella Union Hotel. If Seeley was winning when his ship returned, he might delay leaving port for another day of poker. If he was losing, the Senator ran mostly on schedule.

The Ada Hancock’s other passengers were in a holiday mood, despite the gusty weather. Medora Hereford and her fiancé Henry Myles were accompanied by Maria de Jesus Wilson (the daughter of Benjamin Davis Wilson, whose second wife was Medora’s sister). They chatted with Myles’ business associate, Phineas Banning and Thomas Workman, Banning’s chief clerk. All of Banning’s family had gone on the afternoon excursion:[v] Banning’s pregnant wife Rebecca, her mother Hannah Sanford and brother William Sanford, and Banning’s sons William and Joseph. Mrs. Banning’s maid watched over the boys; Joseph was hardly a year old. They weren’t the only children. A woman – identified only as Mrs. Cohn – was on board with a two-year-old, an infant, and a maid.

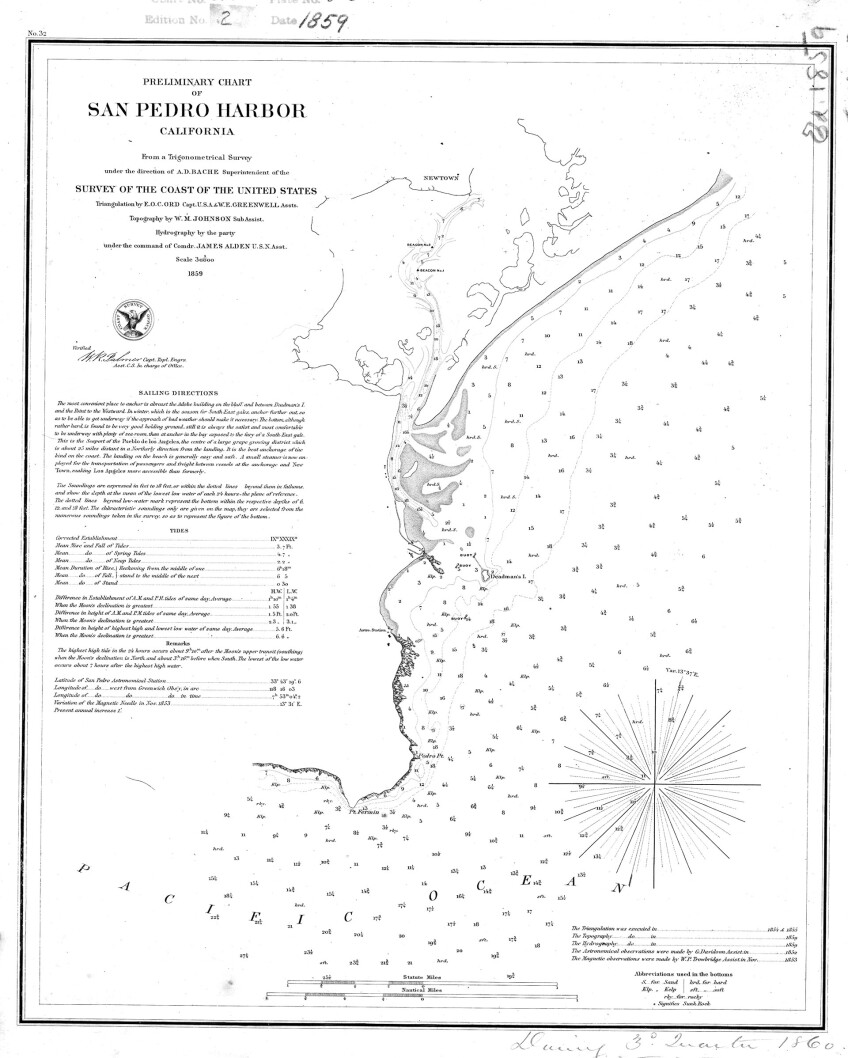

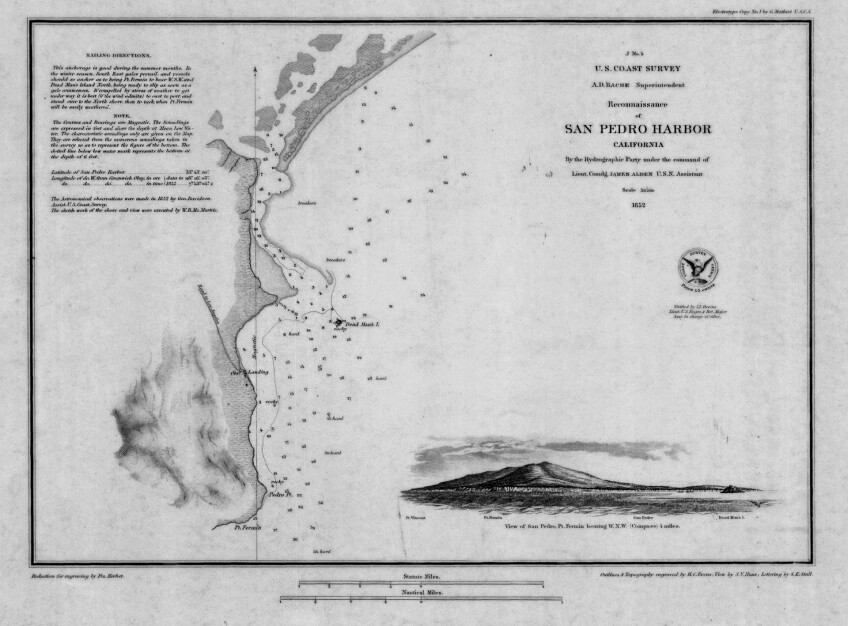

Passage from the shelter of Rattlesnake Island into the deep harbor required Captain Joseph Bryant of the Ada Hancock to make a sharp turn at Deadman’s Island. On the deck of the Senator, about a mile away, watchers saw the tender make the turn.

The wind in the open harbor was much stronger, “blowing almost a gale,” William Waddell later wrote.[vi] Cold gusts struck the cabin of the Ada Hancock, causing the tender to tilt to the left. Because of the wind, some of those standing on the deck moved to the shelter of the cabin, adding to the tilt. Allen Clark, the engineer overseeing the vessel’s engine, noted that water was lapping over the side and onto the deck. To avoid drenching their shoes, passengers hurried to the other side of the deck. The steamer righted itself.

Phineas Banning turned to speak with Captain Seeley of the Senator. Allen Clark thought he should shift the coals in the boiler’s firebox that might have been upset when the tender careened. He turned and reached for a coal shovel. It was sometime between 4:30 and 5:00 p.m.

Those watching from the deck of the Senator began calculating when the Ada Hancock would arrive with Captain Seeley, and how long it would take him to get the Senator underway.

While they watched, the boiler of the Ada Hancock detonated.

Ada Hancock and the Senator

The Ada Hancock had been built in San Francisco in 1858 or 1859 and launched with the name Milton Willis. Driven by twin propellers (rather than paddle wheels), the nimble vessel was designed to work as a harbor tug. At just 60 feet long and well under 100 tons, she was small.

Banning purchased her in 1861 and brought her to New San Pedro to join three similar craft: the Comet, Clara, and Cricket. All of them had a shallow draft, allowing them to work as tenders and tow boats among the harbor’s mud flats. Owing to the Ada Hancock’s dual role as a tug towing freight barges and a tender taking passengers to ships at anchor, Banning had replaced the original boiler with a much larger one in 1862.

Banning also had the tug rechristened Ada Hancock. The new name honored the friendship between Banning and U.S. Army Captain Winfield Scott Hancock. Banning asked Hancock’s five-year-old daughter Ada to perform the ceremony shortly before Hancock and his family left Los Angeles for a post with a Union Army regiment in Ohio.

Banning, ardently pro-Union, may have had a purpose other than friendship. Los Angeles was a secessionist town,[vii] seething with plots early in the war for separating the south of the state and annexing it to the Confederacy. Since the start of the war, several dozen Angeleños had slipped across the Colorado River and into Texas to join the Confederate States army.

If other secessionist sympathizers had to set out to the Confederate States aboard a steamer with the name “Hancock,” by 1862 a celebrated Union Army general, Banning probably was pleased.

The Boston-built Senator was an institution on the coast, having arrived by a perilous voyage of nearly seven months in the autumn of 1849. The ship had come from New York, around the Horn of South America, to San Francisco. Driven by two sidewheels, and still rigged for sail, she had a transitional design that reflected the early years of steam navigation. The Senator immediately made money carrying miners from San Francisco to the Sacramento gateway of the Sierra gold fields. By the early 1860s, miners had been replaced by Southern Californian ranchers, government officials, and businessmen and their families.

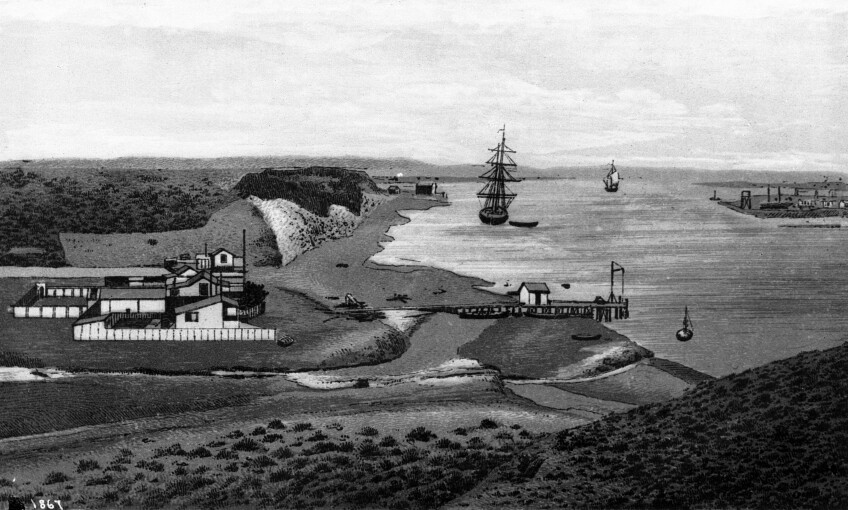

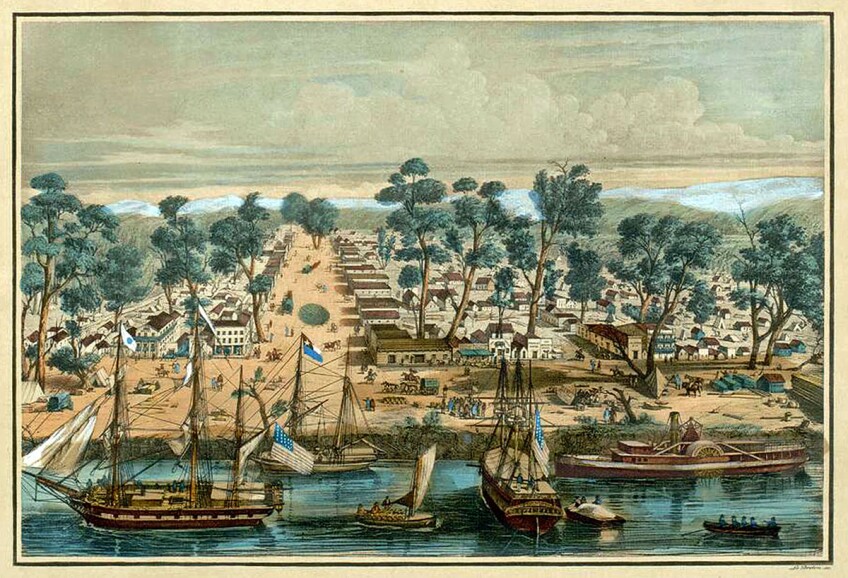

Banning’s Landing

The Senator under Captain Seeley made a brisk circuit from San Francisco to Los Angeles to San Diego and back. The stops at Los Angeles always required the most logistical support, since large steamers like the Senator were forced to load and unload cargo and passengers from tenders. Parts of San Pedro Bay were shallow enough to wade across. Near Banning’s landing in the Wilmington Lagoon, the water was only a foot or two deep at low tide.

Banning’s landing, almost five miles from where the larger ships rode at anchor, was the city’s principal port facility, but it was barely adequate. J. Ross Browne, a former forty-niner turned travel writer,[viii] mockingly described New San Pedro in 1863 as:

(A)n extensive city, located at the head of a slough, in a pleasant neighborhood of sandbars and marshes … The streets are broad and beautifully paved with small sloughs, ditches, bridges, lumber, dry-goods boxes, and the carcasses of dead cattle. Ox bones and the skulls of defunct cows, the legs and jawbones of horses, dogs, sheep, swine, and coyotes, are the chief ornaments of a public character; and what the city lacks in the elevation of its site it makes up in the elevation of its waterlines, many of them being higher than the surrounding objects. The city fathers are all centered in Banning, who is mayor, councilman, constable, and watchman, all in one. He is the great progenitor of Wilmington. Touch Wilmington, and you touch Banning.

Banning, heavy-set and powerfully strong, dominated the harbor. He drove his drayage teams hard to beat the competition carrying passengers to Los Angeles and war matériel to the Union forts along the Colorado River. Banning was a respected businessman, much liked, and he ran his businesses the way he ran his horses.

Wreck of the Ada Hancock

The Ada Hancock explosion was “a crash and roar like the discharge of a whole park of artillery” in some accounts. William Waddell, on board, only heard “a report like a small cannon” before he was tossed into the water by the blast.

The disintegration of the tender’s boiler and superstructure sent a cloud of steam, soot, and wood fragments high into the late afternoon sky. Iron shrapnel cut through the male passengers who had clustered around the boiler. Planks, bodies, and parts of bodies cartwheeled into the bay, some of them landing on a sandbar 40 feet away. Bodies of those who had been scalded to death floated nearby. Of the Ada Hancock, aground in eight feet of water, nothing remained but the hull.

When news of the disaster reached San Francisco on May 1, the Bulletin reported that “… bodies were found at great distance from the wreck, and so general was the destruction that many lives have been lost, of which no record will ever be found.”

Albert Sidney Johnston. Jr. was among the known dead, as was Henry Myles, Medora Hereford’s fiancé; Joseph Bryant, captain of the Ada Hancock; Thomas Workman, Banning's clerk; William Sanford, Rebecca Banning’s brother; Hiram Kimball and Thomas Atkinson, the Mormon missionaries; Fred Kerlin and Charles King, both from Tejon; William Pratt, Richard Price, and Joe (the three “colored” men); and perhaps as many as a dozen more. The nameless Sonoran and teamster also died.

First Mate Butters, in a rescue boat from the Senator, found her captain in the arms of Allen Clark. Although painfully scalded himself, Clark was holding Captain Seeley’s head above water not realizing that Seeley was already dead. Only the head, shoulders, and chest of Henry Oliver were recovered. The body of William Ritchie was found some days later. Louis Schlesinger, John Rodgers (a deck hand on the Ada Hancock), and the men identified only as Levi and Repetto were among those reported missing.

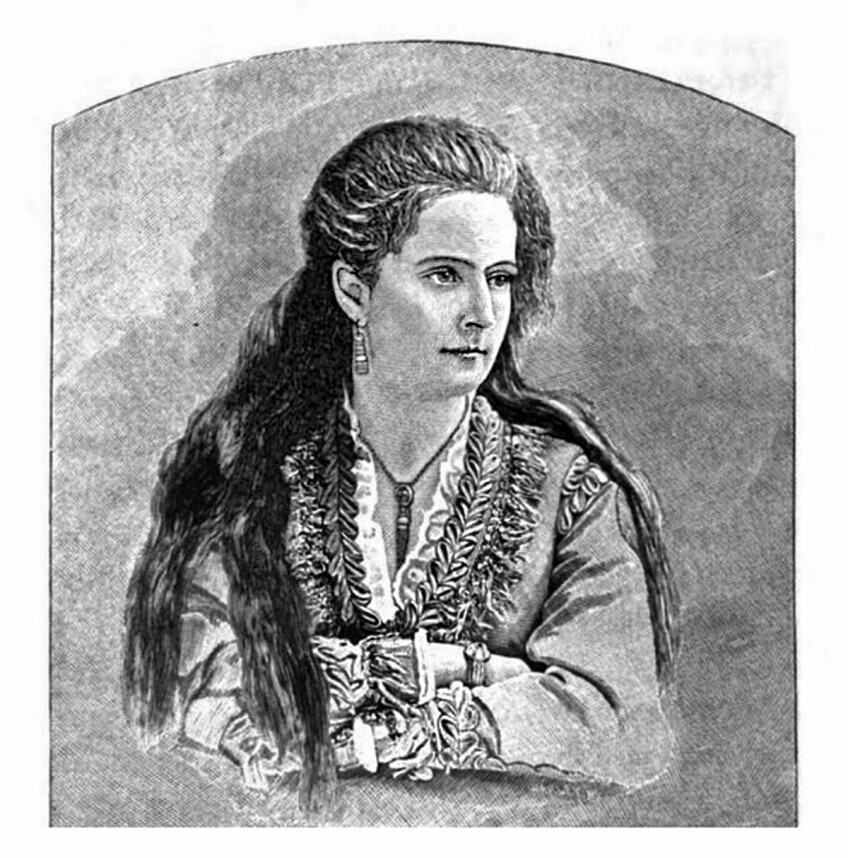

Medora Hereford was rescued but terribly scalded. She died three months later after intense suffering. “Notwithstanding the assiduity of the best professional skill,” noted her obituary in the Los Angeles Star, “and the tender nursing of a fond mother and loving sisters, with all the appliances that wealth could command, (her) injuries could not be reduced – youth and beauty, vigorous constitution and anxious friends were unavailing – death at last put forth its hand and terminated the agonies which no human power could alleviate.”[ix]

Banning survived, possibly because the body of Captain Seeley sheltered him from the blast’s worst effects. Thrown into the shallows around Deadman’s Island and suffering from a concussion, Banning was found “crawling out of the water up the bank of the creek, on his hands and knees,” his mind wandering. Early reports expected him to die.

The less badly injured aided those who were struggling in the water. First Mate Butters told the Sacramento Union of seeing[x]

… a grayheaded man, whose name he could not learn, who acted like a hero. He was standing on the wreck, holding a wounded person's head above the water, and when asked if he was hurt, said no – not half as much as others about him. After rescuing those around, they took the old gentleman into the (skiff), and found his leg was broken. He had, with the consciousness of his own injuries, helped all about him, only to be relieved when the rest had been picked up. Those in the boat could hardly believe it possible his leg was broken, from his coolness and total unconsciousness of self, and desire to help those worse off than he was.

The “grayheaded man” Butters saw was probably Santa Cruz lumberman William Waddell, who described the aftermath of the explosion in a letter to his daughter sent on April 30:

I … came to the top of the water about thirty feet from what had been a small steamer a minute before, but was now a mass of splinters and floating boards. I swam to the hull and got on it, as it was partly out of water, the tide not being full. I assisted a man who was hurt to get up safely. I next got a small child about two years old, which I kept wrapped up in my coat until its mother claimed and took it from me. About this time I discovered my leg was broken below the knee, and I could no longer render assistance to others. All this time I was in water up to my knees and remained so until the last boat left the wreck, which was one and a half hours from the explosion.

Waddell may have rescued Mrs. Cohn’s oldest child (described as being about two years old in some newspaper accounts). Mrs. Cohn was slightly injured as was her infant child, who was carried from the wreck by Mrs. Cohn’s uninjured servant. Banning’s two boys were kept safe by Rebecca Banning’s “colored servant,”[xi] although one boy was slightly scalded. Rebecca Banning suffered internal injuries, and the infant she bore in October died soon after, probably as a result of the trauma. Mrs. Sanford suffered a broken right leg and a broken left arm. Maria Wilson survived with a superficial wound. There were other broken limbs, scalds, and contusions.

Medical aid initially came from the infirmary at Camp Drum, the US Army post that guarded the harbor. “The awful news, casting a general and indescribable gloom,” Harris Newmark later wrote, “was not received in (Los Angeles) until nearly eight o'clock, when Drs. Griffin and R. T. Hayes, together with an Army surgeon named Todd, hastened in carriages to the harbor …”

In most accounts, fewer than six or seven of the more than 50 passengers on the Ada Hancock escaped injury. At least 26 died. J. S. Benton, purser of the Senator, provided San Francisco newspapers with the names of travelers who had booked passage from Los Angeles, but not all the lists agree, even on the spelling of names. No passenger manifest was made of all those on the afternoon’s excursion on the Ada Hancock.

“Apathy and Negligence”

Despite his injuries, Banning had a business to run. He sent for Frank Lecouvreur, a former employee, for immediate help. Lecouvreur was shocked when he arrived at the Banning warehouse that evening:[xii]

When I entered the large warehouse, so well known to me, I found it partly turned into a morgue, as more than twelve bodies had already been brought in and stretched out on primitive frames. In some cases it was impossible to recognize them, as even the very features were distorted or torn to pieces. … With a number of good men I started the routine work of sorting a few tons of freight in the warehouse, where the victims had found a temporary resting place. … (W)henever a new body was brought in from the shore and we recognized the well known figure of some honest co-worker, our hearts grew weak and work went on slowly. Then came calls from mourning friends, whose piercing cries would melt the coldest hearts.

Newmark’s own heart was troubled when he witnessed the return of young Albert Sidney Johnston’s body to the home of his mother: “… (W)ords cannot describe the pathos of the scene when she addressed the departed as if he were but asleep.” There were other sad homecomings in Los Angeles that night. “Few there were who had not friend or relative on board the boat,” noted the Star.

At New San Pedro, the friendless dead and those too mangled for identification were summarily buried by soldiers from Camp Drum.

Newmark also noted that the strongbox with $11,000 in gold dust accompanying William Ritchie had not been found, although soldiers had searched for it as part of the rescue effort. Despite the soldiers’ presence, Fred Kerlin’s $30,000 in bank notes disappeared too, along with the cash and jewelry of the dead. “From these circumstances,” Newmark added, “it was concluded that, even in the presence of Death, these bodies had been speedily robbed.”

On May 3, Major Clarence Bennett, commanding at Camp Drum, issued a “general order” thanking the officers and enlisted men for their quick response to the Ada Hancock disaster. But he also felt forced to echo Newmark’s criticism:[xiii]

The conduct of the whole Command reflects the highest credit upon American Soldiers, and it is in marked contrast with the apathy and negligence displayed by persons living in the vicinity of Los Angeles, who previously claimed to be the intimate friends of some of the deceased and suffering survivors.

Unfeeling or not, the Senator sailed after only a brief delay, carrying the body of Captain Seeley. Ships in San Francisco Bay – even a Union warship at anchor – dipped their flags in respect as the Senator passed on April 30. Seeley was buried the next day, following funeral services at Trinity Church. He had been a popular captain, and the attendance was large.

Official Inquiries

On May 2, Justice of the Peace Benjamin Smith Eaton, acting as corner, assembled a jury of inquest on the deaths caused by the Ada Hancock explosion. Allen Clark, the vessel’s engineer, testified that he “considered the boiler very good; made of best quality of material” and running well under the safe pressure limit. “In my opinion, the explosion was caused by the extraordinary careening of the boat … causing the (boiler) tubes to become heated, and when the boat righted the water coming in contact with the heated tubes created a gas, which caused the explosion.” The jury agreed and found “that no culpability can be attached to the officers or owners of the boat, but that the accident is entirely attributable to the overpowering force of the elements.”[xiv]

The Sacramento Daily Union offered a slightly different theory. “The tide being very low before starting, water could not well be pumped into the boiler without drawing in the mud. The passengers may have been a little late, and each moment of delay exhausted a certain amount of the water in the boiler. By the time the steamer was all ready to start, the water would, in all probability be low. After running the short distance she did, and getting into deeper water, the pumps may have been started, and the cold water coming in suddenly, may have caused the explosion.”[xv]

William Burnett, a member of the federal Board of Supervising Inspectors of Steamboats,[xvi] rejected the “force of the elements” theory. The Ada Hancock was destroyed and lives lost because of recklessness and incompetence – a demonstration of the need for better federal regulation of steamships and their operation.

Burnett declared that the steam tug was “unlawfully engaged in carrying passengers,” a circumstance permitted by the lax oversight of customs officials at the Los Angeles port and Banning’s failure to apply for the required inspection and passenger service certification. “No such application was ever made,” Burnett complained, “and no information of her being … unlawfully engaged was furnished the inspectors until after the explosion. The [Ada Hancock] never had been inspected as far as can be ascertained – certainly not as a passenger steamer.” Burnett also noted that the vessel “had a boiler unusually large for the size of the steamer,” which contributed to its total destruction and the number of casualties.

Burnett singled out Allen Clark, the Ada Hancock’s engineer, as the probable cause of the disaster. “The person employed as engineer had never been licensed by the inspectors; and, as his experience is known to them, could not have received, upon application, a license which would have enabled him to take charge of any steamer.”

Burnett’s conclusion: Banning broke the inspection laws for his own convenience, installed an oversize boiler that magnified the disaster, and hired a dangerously incompetent man to run it. “… (B)ut for the neglect of the owners to have this vessel inspected and the machinery put under proper and lawful management, this casualty might, in all probability, have been avoided.”

Despite Burnett’s official condemnation, Banning’s continued operation of the port wasn’t affected. He was too important to the Union war effort to ostracize.

Aftermath

Despite the emotional impact the disaster had on Los Angeles, its effects were swallowed up in the “famine year” of 1863-1864, when a second year of drought led to the collapse of Southern California’s cattle-based economy. The decline of the Californio rancheros and the Yankees who had married into the cattle aristocracy had begun.

The hopes of pro-secession Los Angeles also withered in the decisive Civil War summer of 1863. Defeat at Gettysburg stopped the advance toward Washington of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant took finally Vicksburg, giving Union forces control of the Mississippi River.

Benjamin Davis Wilson, whose daughter had been injured and whose sister-in-law and her fiancé had died in the Ada Hancock explosion, suffered his personal losses and each Confederate defeat. Wilson, an ardent secessionist, sank into depression.

Although spared the worst impacts of the Civil War, most Angeleños resisted aiding the war effort or assisting wounded Union soldiers. As one contemporary author pointedly noted, “Of all the examples of subtle disloyalty in Los Angeles County, perhaps the most significant had been its failure to support the United States Sanitary Commission and its companion agency, the Christian Commission.”

First Mate Butters was made captain of the Senator, but Newmark thought Butters had risen above his abilities. “Just what his real fitness was, I cannot say; but it seemed to me that he did not know the coast.”

The Wells Fargo strongbox remained lost. The California Supreme Court later determined that the company was required to repay George Hooper, the merchant from Yuma who had consigned the $11,000 in gold dust. The precedent expanded the legal definition of a “common carrier.”

Despite several days of advertising for them in the Los Angeles Star, Henry Oliver’s stock certificates and business papers were never found.

Eliza Johnston remained in Los Angeles to mourn the deaths of her husband and son. She turned for support to her brother, Dr. John Griffin, one of the city’s first physicians and himself, like his sister, a southerner and secessionist.

The presence of federal troops at New San Pedro and the defeat of Confederate States forces in Arizona quieted efforts to join Southern California to the Confederacy. Resentment and distrust lingered. More than a few Angeleños cheered the news of President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865.

Banning recovered from his injuries and continued to prosper after the war. In 1869, he built the city’s first steam railway. It went from his dock and warehouses to Los Angeles.

18-year-old Ada Hancock died of typhoid fever in 1875. Civil War hero Winfield Scott and his wife Almira were crushed by their daughter’s death.

Notes

[i]. By 1860, port facilities at “Old” San Pedro had declined in favor of New San Pedro, a settlement sheltered behind Rattlesnake Island and carved out of the surrounding mud flats by Phineas Banning in the early 1850s. It would later be officially named Wilmington.

[ii]. Albert Sidney Johnston had resigned his Army commission and joined the forces of secessionist Texas shortly after the start of the war. He was killed at the battle of Shiloh in 1862.

[iii]. Various sources give his name as Loeb Schlessinger or Schlossinger.

[iv]. Several of them, like Henry Oliver, were miners or mining engineers from Laguna de la Paz who had joined the Colorado River gold rush of 1862.

[v]. Sources differ on the reason. In some accounts, 21-year-old Maria Wilson was sailing for San Francisco; in others, Henry Myles and Medora Hereford planned to marry there. Members of the Banning party went out on the Ada Hancock to see them off.

[vi]. “William W. Waddell” entry in E. S. Harrison, ed., History of Santa Cruz County (San Francisco: Pacific Press Publishing, 1893), p. 235

[vii]. So contemptuous were they of Union sympathizers that Texan colonists from El Monte (and other secessionist Angeleños) threatened violence to disrupt the city’s Fourth of July celebrations in 1862. The threats continued in 1863, when no commemoration was held.

[viii]. J. Ross Browne, Adventures in the Apache Country: A Tour through Arizona and Sonora, etc. (New York: Harper Brothers, 1869), p. 34.

[ix]. “Obituary,” Los Angeles Star, July 18, 1863, p. 3

[x]. “The Late Explosion and Loss of Life,” Sacramento Daily Union, May 4, 1863, p. 4

[xi]. Only one contemporaneous newspaper report named Mrs. Banning’s “colored servant girl,” whose somewhat improbable name is given as “Darkness.” She earned the reporter’s special praise however. She “displayed undaunted courage and rendered great assistance to numbers of others. During the whole excitement she remained perfectly calm, and was the means of keeping several of the ladies' heads above water for some time after the vessel had gone down.”

[xii]. Frank Lecouvreur, From East Prussia to the Golden Gate, Julius C. Behnke, tr. (Los Angeles: Angelina Book Concern, 1906), p. 315

[xiii]. “General Orders – No. 15,” Los Angeles Star, May 13, 1863, p. 2

[xiv]. “Horrible Catastrophe,” Los Angeles Star, May 2, 1863, p. 2

[xv]. “The Late Explosion and Loss of Life, ” p. 4

[xvi]. Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances for the Year 1863: Annual Report of the Board of Supervising Inspectors of Steamboats (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, November 1863) p. 176