Harris Newmark: Jewish Patriarch, Pioneer Businessman, Angeleño

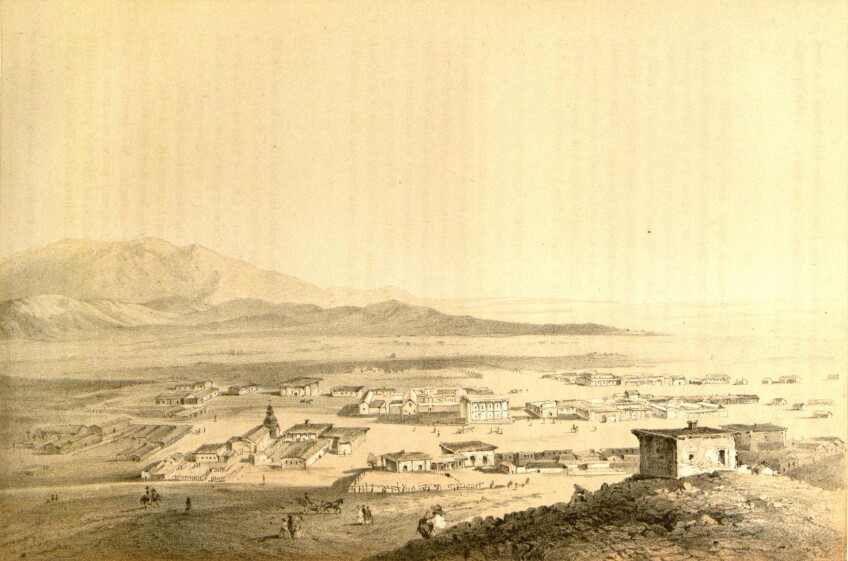

Los Angeles was a city made of mud – of adobe, which is dried mud – when Harris Newmark arrived in 1853. He had come to California, as many did in the mid-19th century, for something better than his birthplace, better than his life in Löbau in Prussia (now Lubawa, Poland), better than working for his father in the manufacture of ink and boot blacking to be wholesaled to retailers in Denmark and Sweden, and better than sales trips in miserable weather on poor roads or over rougher seas. Newmark was just 19; of course he was willing to leave when his older brother wrote from Los Angeles offering him passage money.

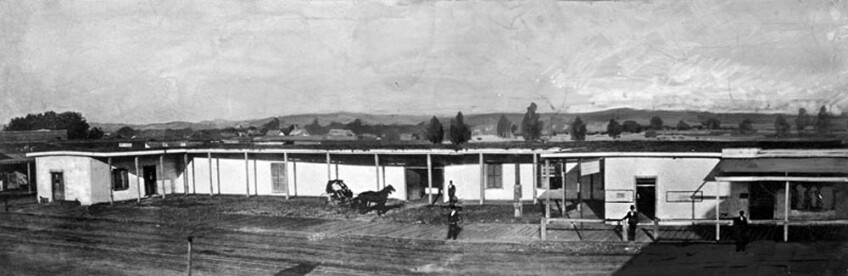

Passage to golden California, where the whole world had lately rushed in to get rich panning and sluicing the banks of the American and Sacramento rivers. Newmark’s enterprising brother had bought into the California dream, but not in the gold fields. He partnered with Jacob Rich in a wholesale dry goods store at the corner of Main and Requena streets in Los Angeles. It was “a site so far out town,” Newmark later remembered, that there would hardly have been any retail customers. (The location today is behind Los Angeles City Hall.)

“When I came, Los Angeles was a sleepy, ambitionless adobe village with very little promise for the future,” Newmark wrote in the closing lines of “Sixty Years in Southern California: 1853-1913”. Los Angeles then was small, violent, hard drinking, and far from the rest of America, but it also was a city in which successful shopkeepers – Newmark was destined to be one – could greet their customers in English, Spanish, Italian, and French. Like his contemporary Antonio Coronel, to be successful Newmark had to negotiate the complex ethnic borderland that was mid-19th century Los Angeles, with its mix of bachelor Jewish merchants, Mexican vaqueros, Yankee businessmen, and Californio landowners. In a parallel with some immigrants today, Newmark learned to speak Spanish before he acquired English.[1]

Newmark had come from another, equally complicated eastern European borderland in which German speakers overlapped with Polish speakers in a politically contested zone. There, Jews like Newmark’s parents had once been Polish and marginalized and now were German and tolerated. The experience must have given Newmark an advantage over his business competitors.

We don’t know what Newmark’s brother wrote to him about Los Angeles. Presumably, his brother described the town’s commercial possibilities. But did he explain how primitive Los Angeles was? That it had no sewers, sidewalks, or banks? That it had no civic institutions at all (unlike even provincial Löbau)? That life – particularly the lives of Native Americans and mestizo laborers – was held cheaply, and murder was common? That in Los Angeles Newmark would be an anomalous presence among the town’s 1,600 residents with, according to the 1850 census, only eight (all unmarried) who were Jewish?

But one of them – Morris Goodman – had been elected to the first city council under American authority in July 1850, a fact that Newmark’s brother might have pointed out to him.

What Los Angeles did have was economic fluidity. The city offered many pathways to success: shopkeeper, broker, wholesaler, financier, rancher, grower, and real estate developer. Newmark took all these routes, often combining three or four of them through the 1850s and 1860s.

As significant for the growing number of Jewish residents was a degree of social fluidity in Los Angeles that even Gold Rush San Francisco lacked.[2] The city’s many fragmentations – its essential cultural incoherence – allowed multiple forms of passing between American, Californio, European immigrant, and Mexicano communities. Just as Antonio Coronel could be the spokesman of an antique Californio culture and California’s State Treasurer, Harris Newmark could be a founding member of Congregation B’nai B’rith, a leader of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, and board member of the Southwest Museum.

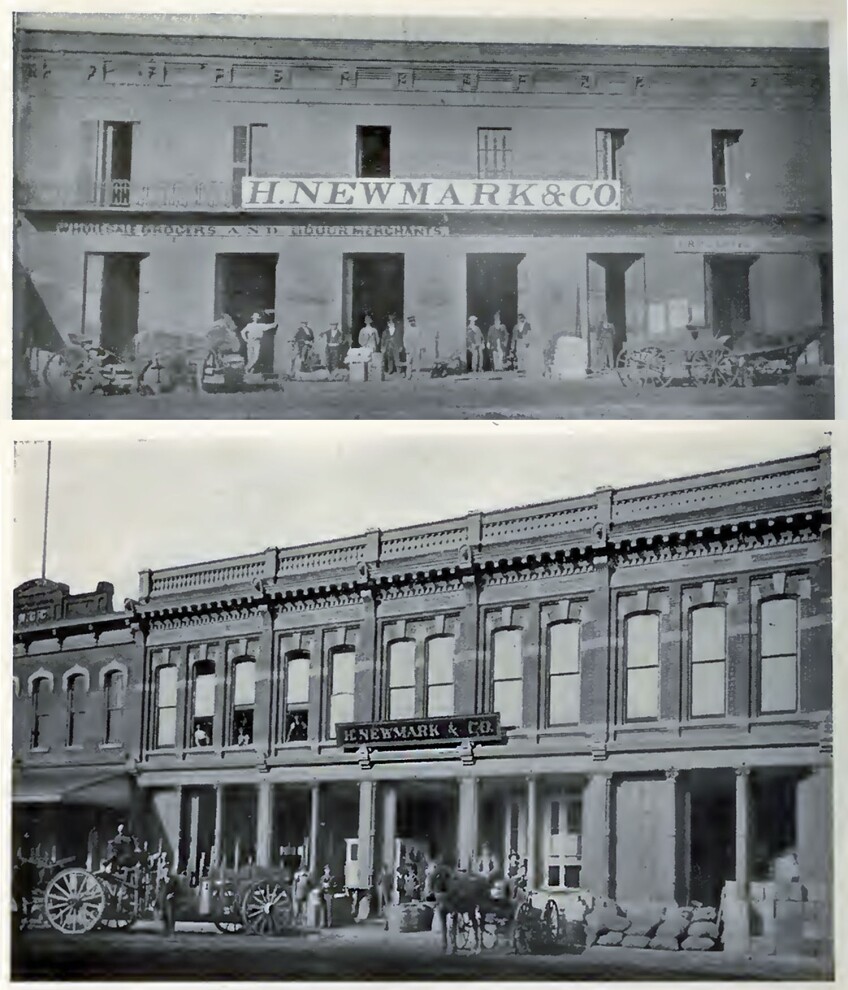

A considerable part of Newmark’s business success in the mid-1860s came through his friendship with Mormon leader Brigham Young and with it an exclusive contract to supply dry goods to Salt Lake City. Newmark and Young did business partly because both were provisional Americans on the margins of an increasingly Protestant and prejudiced West. A boastful Prudent Beaudry, then Southern California’s largest dry goods wholesaler, claimed “he would drive every Jew in Los Angeles out of business.” Newmark’s response was to cut a sweetheart freight deal with Phineas Banning, lowering Newmark’s overhead costs and leading, he thought, to the failure of Beaudry’s business in 1866. H. Newmark & Co. was then the city’s biggest shipper, broker, and wholesaler.

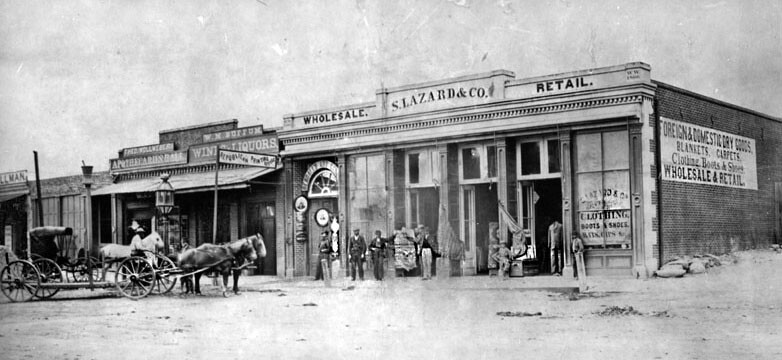

American Los Angeles through the 1870s was racially bigoted but not overtly antisemitic, despite Beaudry’s slur against his Jewish competitors. In fact, Beaudry later set up the city’s water company in partnership with Solomon Lazard, one of the founders with Newmark of the Hebrew Benevolent Society and the husband of Newmark’s cousin. Lazard was one of several French Jews who opened retail businesses around the old plaza. Three of them eventually married into Newmark’s family.

Newmark and his extended family were woven into every aspect of late 19th century Los Angeles. Harris Newmark’s uncle served informally as the Jewish community’s first leader, until he recruited Rabbi Abraham Wolf Edelman to lead Congregation B’nai B’rith. Newmark himself was the president of Congregation B'nai B'rith in 1887 and a founder of the Jewish Orphans Home. He also was one of the founders of the Los Angeles Public Library and the Library Association. As one of the city’s largest business owners, he was a founding member of the Board of Trade, successor to the Chamber of Commerce, and later president of the association of dry goods wholesalers. He also purchased the Repetto Rancho and subdivided a large part of what is now Montebello (originally named Newmark).

Newmark’s sons took up their father’s roles in business associations, civic institutions, social clubs, and Jewish service organizations. Newmark’s cousins, nephews, and sons-in-law did as well and joined partnerships with the non-Jewish entrepreneurs who built the infrastructure of the city.

Family members also served in city and county government, a civic role that Harris Newmark declined. He did accept a last-minute commission in 1872, at the request of the Los Angeles Board of Trade, to join former governor John G. Downey in negotiating with Collis Huntington, the head of the Southern Pacific Railroad and the most powerful man in California. The Southern Pacific, building a new line from San Francisco through the Central Valley, seemed to be aiming toward Los Angeles, but the railroad’s local agents made no promises. Huntington wanted what he always sought, exclusive access to a new market and abject compliance – in the form of a large subsidy – from Los Angeles residents.

Newmark, the other leading businessmen of Los Angeles, and the county’s Board of Supervisors were willing to knuckle under, given Huntington’s promise of favorable treatment and quick completion of the line. County voters, despite strong opposition, agreed to a subsidy that included land for a train station and the city’s entire stake in the existing rail line between the port at Wilmington and downtown (a line that Huntington would then control). The value of the subsidy was an estimated $610,000, an enormous sum. (As stipulated in the agreement with the railroad, the subsidy was five percent of the taxable value of all the property in Los Angeles County, which then included what is now Orange County.)

The effort to link the city to the transcontinental rail system (which was through San Francisco until 1881) assembled a uniquely Los Angeles coalition of supporters.[3] The railroad committee included Newmark and Andrés Pico (Californio patriot and one of the signers of the Capitulation of Cahuenga), former California State Treasurer Antonio Coronel, real estate developer and former governor John Downey, lumberman John H. Griffith, ranchers Henry Dalton and Leonard Rose, City Council President H. K. S. O’Melveny, former County Supervisor D. W. Alexander, and future California governor George Stoneman.

As costs to complete the line rose and the Southern Pacific demanded an additional $250,000, Newmark and Solomon Lazard helped to organize the business community’s support. Later, when the railroad used its monopoly to impose much higher shipping costs in 1876, Newmark and other wholesalers chartered the freighter Newport to bring goods to Los Angeles by sea.

But the solidarity of the city’s business community was eroding. Newmark eventually stood alone in trying to weaken the railroad’s freight monopoly. He gave up and accepted the new rates. Successful businesses were now operating statewide and the old, freewheeling days of the pioneer merchants were ending. Passage across the ethnic and cultural boundaries of Los Angeles was becoming harder, too. New immigrants from the Midwest brought their bigotries with them, including overt antisemitism.

Newmark, ever the careful negotiator of the borderlands of Los Angeles, only alludes to the social clubs and booster organizations that, beginning in the late 1880s, no longer admitted Jewish members, beginning the long estrangement of Jewish business leaders from civic life in Los Angeles.[4] The effects of that separation still linger.

Harris Newmark died a hundred years ago, shortly before the publication of his memoir – almost a day by day account – that remains the most readable and reliable of witnesses to the newly American Los Angeles of the mid-19th century. Although Newmark continues to be honored by the city’s Jewish community as one of its founders, his identity as an Angeleño has faded.[5]

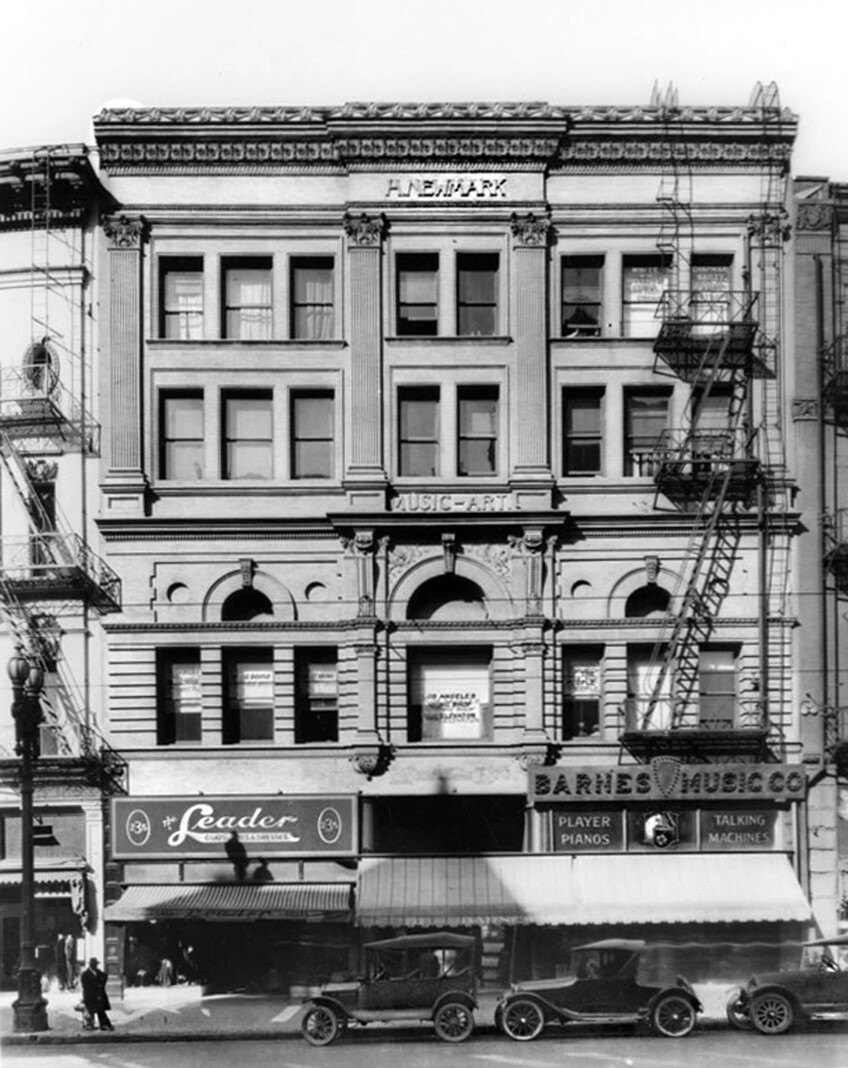

Harris Newmark High School (on the grounds of Belmont High) and Newmark Mall (a collection of shops in Montebello) fleetingly remember his name. The Harris Newmark Building, built in 1926 by Newmark’s sons, is now the New Mart.

Newmark, who had navigated the mean streets of the 1850s, was bolder than the quiet, elderly businessman described in his obituaries. He and his contemporaries – Californio, Mexicano, Anglo, European immigrant, and Jewish – were thoroughly Western in spirit, flawed but generous. They took their diversity for granted and, for the most part, chose not to turn their differences into grievances. Imperfect people in an imperfect place, they were proud to call themselves Angeleño.

The second edition of Harris Newmark’s “Sixty Years in Southern California: 1853-1913” is available in digital form from several sources, including the American Memory Collection of the Library of Congress.

Notes

[1] When Newmark’s uncle, his wife, and their children – all of whom spoke English – joined him in 1854 in Los Angeles, they quickly taught him English.

[2] Historian Kevin Starr has described 19th-century California as a “ferociously fluid society.”

[3] The Santa Fe Railroad completed a direct transcontinental rail line to Los Angeles, breaking the Southern Pacific’s monopoly in 1887.

[4] “Speaking of social organizations,” Newmark wrote, “I may say that several Los Angeles clubs were organized in the early era of sympathy, tolerance and good feeling, when the individual was appreciated at his true worth and before the advent of men whose bigotry has sown intolerance and discord, and has made a mockery of both religion and professed ideals.”

[5] Harris Newmark, writing in 1913, continued to use the term Angeleño (with an enye) to name both Anglo and Latino residents of Los Angeles. This is what also called himself.