How Two African American Artists Explored the Roots of Racism on the West Coast

On a morning in late August 1948, artists Charles Alston and Hale Woodruff approached a lone historical marker in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The duo was midway through a two-week tour across California. They had arrived at Beckwourth Pass, the lowest navigable trail in the formidable range. In the heat of the chaparral, the wool-suited men began sketching the remote valley and sagebrush hills. Leonard Grimes, a young public relations agent accompanying them from Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company (GSM), photographed the working pair.

The travelers stopped for a cold beverage at a restaurant near Hallelujah Junction. The proprietor refused their money, and the men left emptyhanded and discouraged. Racism, Grimes recounted to his employers, met them "at the mouth of a path discovered by a Negro trapper — a path discovered by a man whose skin was as dark as ours, a discovery that enabled this man to refuse three other Negroes a glass of water to make a living."

This was not the trio's first encounter with prejudice, but it reinforced their purpose in undertaking the trip. Earlier that year, the African American artists were hired from New York to design a monumental mural for the lobby of GSM's new Home Office Building in Los Angeles. Founded in 1925, the company was by 1945 the largest African American-owned enterprise in the American West, known for its equitable loans and life insurance policies. In 1947, it commissioned master architect Paul Revere Williams to design a modern headquarters in West Adams. The building looked to the future, whereas the mural would recover an erased Black past.

More from Lost L.A.

Alston and Woodruff each had to his name a dynamic body of work exploring the aesthetics, struggles and historical consciousness of the African Diaspora. Their business in California, however, carried them to new ancestral landscapes. They crisscrossed the state in search of historic landmarks and artifacts, retracing by highways and automobile the centuries-old footsteps of Black explorers, settlers and leaders. Along the way, they encountered not only their triumphs and tragedies, but also the hardships these pioneers faced in their "battle[s] for a place in the sun." Their mission was to assemble a new memory site in Los Angeles out of many, one that would illuminate the accomplishments of their forebears while arguing for full integration into postwar life.

Alston, Woodruff and Grimes departed Los Angeles for San Diego on August 20. There, they visited the Junípero Serra Museum, La Casa de Estudillo and the Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá. In each of these places, they sketched and photographed the architecture, reviewed historical manuscripts and museum objects and inquired about notable Black figures.

That evening, they attempted to check into the U.S. Grant Hotel, where the company had arranged for their lodging. The hotel clerks resisted but eventually acquiesced. Grimes reported that their "quiet persistence" would "help the local citizens in their fight to break down racial discrimination." Over the course of the trip, the artists eschewed hotels known to be friendly to Black travelers — those popularized in "The Negro Motorist Green Book," for example — in favor of exclusive accommodations.

The trio continued investigating California's Spanish colonial heritage as they journeyed north along the Mission Trail. They observed the textures of the landscape, changes in climate and the tenor of the people.

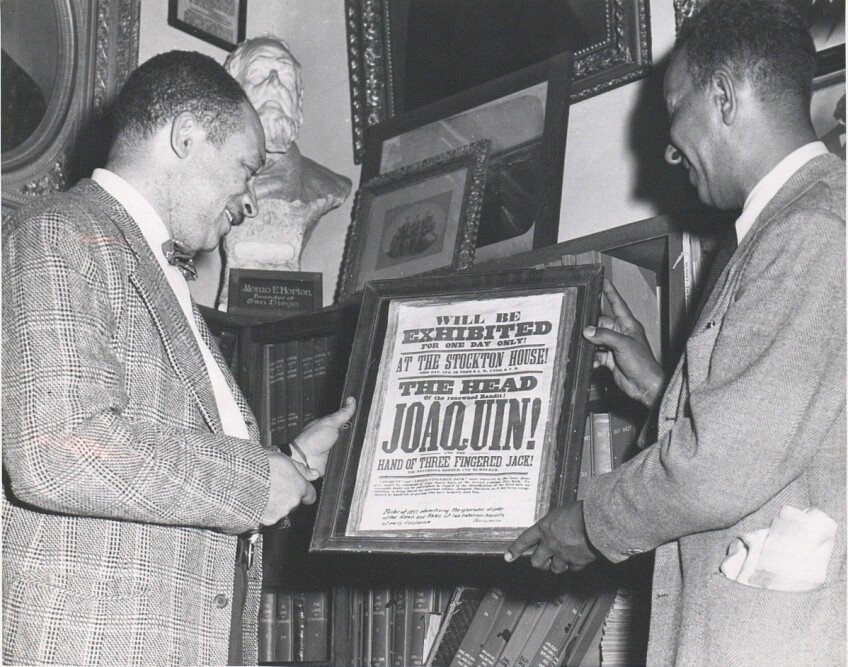

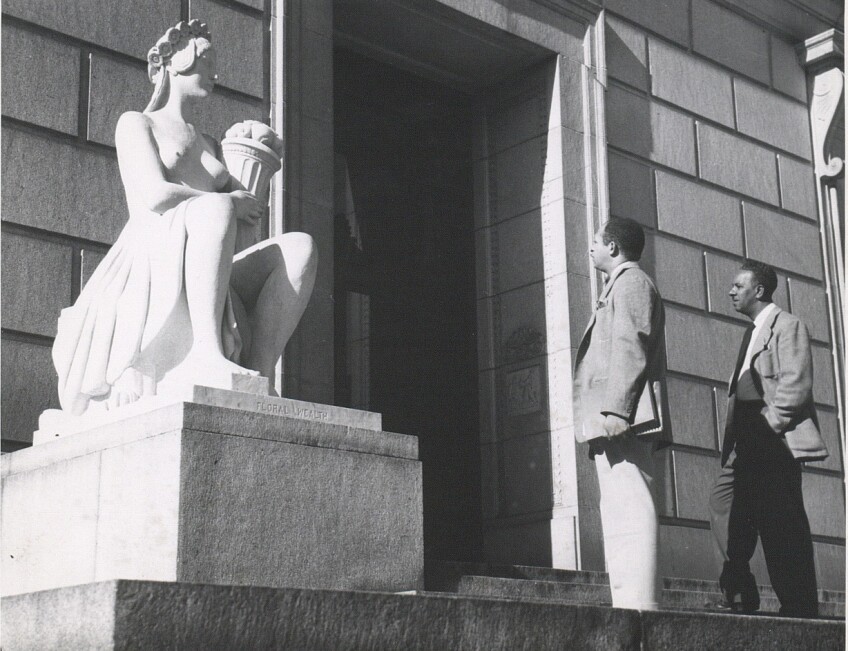

Arriving in the Bay Area, Alston and Woodruff procured historical newspapers, census records, photographs and letters from the Bancroft Library in Berkeley. In San Francisco, they dipped in and out of antique shops, bookstores and museums and lingered over murals at Coit Tower and Rincon Annex Post Office, which offered sympathetic portrayals of multi-ethnic workers.

The travelers left San Francisco as the sun rose on August 28, following the Feather River Canyon Route into the ghost towns of the Sierra Nevada. They spent two days exploring Beckwourth Pass and Donner Trail. Grimes reflected: "The Negro in California in the early days had a hard time…Due to the color of his skin, he was subjected to almost every outrage that one can imagine. He was murdered, cheated, denied the rights of a human being, herded off in small groups to himself and subjected to all other indecencies that the human race seems of capable of subjecting other members of that race. In this country where he labored and sweated, found a new nation, this condition still exists to some extent." The encounter at Hallelujah Junction shook the trio. "[T]his mural will not be a pretty picture," Grimes cautioned, "it will be a correct picture, [and] it will be an honest one."

Alston and Woodruff ended the joint portion of their trip in Sacramento, where they toured Sutter's Fort. They poured over documents in the California State Archives, which offered them nearly "every source of material in relation to the Negro history in California that one could find." Woodruff remained in Sacramento to meet with archivists, while Alston and Grimes made their way south to Los Angeles.

The artists met their patrons at GSM's office on Central Avenue in early September to recount their journey. Seated around the table were Alston and Woodruff, historian Titus Alexander, librarian Miriam Matthews, executives George A. Beavers, Jr., Norman O. Houston and Edgar Johnson, and public relations administrators Grimes and Verna Hickman.

Alston and Woodruff proclaimed they had captured the "essence of the state." They narrated celebratory episodes, like the courage of frontiersmen who rode with the Pony Express and organized political conventions in the 1850s and '60s. Yet one observation from the road struck them above all, namely, how Black Californians encountered racism in relation to other groups. Acknowledging that many traveled west in bondage, Woodruff described how early African Americans "inherited" legal restrictions and attitudes formed against "Chinese and other non-white groups." He credited civil rights attorney Loren Miller with enlightening him, explaining that 19th-century politics of Chinese exclusion revealed how white supremacy differed in California from other places. Anti-Asian racism and not slavery, he argued, structured discrimination, and white settlers mobilized legislative and vigilante tactics against other migrants in turn.

The artists forewarned that separating Black social, political and economic trials from those of other groups would prove challenging and ill-advised. To neglect the "closeness of cooperation between all races who happen to be a part of the founding or the development of California" would replicate the erasures in the state's civic memory they were striving to overcome. Vice President Edgar Johnson agreed, declaring the mural "must not be racial."

Yet race shaped the mural from conception to installation. The artists divided the artwork into two panels: first, "Exploration and Colonization;" and second, "Settlement and Development." They showed, in rich and deep colors, how generations of Black migrants participated in European and American conquests of California, reflected on the lives they created as free settlers and laborers, detailed the infrastructure they built and illuminated their political movements. Other groups, including Chinese immigrants and Native Californians, ultimately faded into the background. The artists left few clues revealing why their multiracial vision narrowed, although pressure from GSM likely contributed. Over the following year, their patrons requested they soften depictions of violence and urged them to make the characters appear "more Negroid." Years later, Alston expressed frustration with mural-making, explaining to cultural critic Albert Murray that corporate sponsors tended to limit the artist's power of interpretation.

In August 1949, "The Negro in California History" debuted to fanfare in the newly completed Home Office Building at 1999 W. Adams Boulevard. Though GSM closed its doors in 2009, the building and its artwork are protected as Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #1000.