George Freeth: King of the Surfers and California's Forgotten Hero

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

In collaboration with the University of California Press and the California Historical Society, Lost LA is proud to present selected articles from California History that shed light on themes discussed in the show's second season. This article originally appeared in the Summer/Fall 2001 edition (vol. 80, no. 2-3) of the journal.

Not far from the crowded shoreline of Waikiki Beach is the final resting place of a native Hawaiian who forever changed California and its image to the world.1 Beneath the Freeth family tombstone is his simple burial marker. Only the engraved lettering "G.D. 1883-1919" designates it as his grave. The small grave site makes no mention of George Douglas Freeth, Jr., as having been awarded the nation's highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal. Nor does it indicate that he is considered the father of modern ocean lifesaving. No mention is made that he was the person who first demonstrated and taught the sport of surfing in southern California. Within the serene tropical con fines of Oahu Cemetery, however, the light winds blow eastward toward the mainland, seemingly carrying the gentle spirit of the man whose impact on such California icons as ocean lifeguards, surfers, swimmers, and water-polo players, is still felt in modern times.2

George Douglas Freeth, Jr., was born on the Hawaiian island of Oahu on November 9, 1883, to a well-connected local family. His maternal grand father, whose grave is only a few feet from his own, was London-born William Lowthian Green. Although a once-failed California gold prospector, Green earned a substantial fortune in Hawaii by helping to found an inter-island shipping company. He also co-founded and later managed the highly profitable Honolulu Iron Works. Well-educated and blessed with a hearty adventurous spirit, Green, in 1880, became Hawaii's Minister of Foreign Affairs.3 His daughter, Elizabeth Kaili, who was one-half Hawaiian, married Englishman George Freeth, Sr., on December 16, 1879. The union produced six children, of whom George, Jr., was the third of four boys and two girls.4

At an early age the younger George took to the ocean. He excelled at both swimming and diving. At a time when island newspapers proudly boasted that Hawaii was "the home of swimmers," George was selected captain of the prominent Waikiki-based Healani swim team.5 In an age before radio and television, large numbers of tourists and islanders would congregate to attend local water carnivals. It was during these events that a youthful Freeth first made his mark as a gifted waterman. Although a pre eminent champion swimmer, he proved to be a crowd favorite with his skills on the high dive. To the delight of spectators and the admiration of competitors, he performed "high and fancy" dives, many of which had never been seen. Among those who witnessed and admired George's aquatic prowess was the young Duke Kahanamoku. Kahanamoku, who later rose to legendary status in both the sports of swimming and surfing, became a life-long admirer and friend of the older Freeth.6

While Freeth enjoyed exceptional athletic success in community swimming pools, it was in the ocean where he excelled. Waikiki Beach was near the fam ily home. There, with its tropical setting, warm ocean temperatures, and slow rolling surf, he spent much of his early life. It was also in these waters that George first attracted international attention from the pen of middle-aged travel and adventure writer Alexander Hume Ford. Ford, who later gained fame for his ceaseless pro motion of Hawaii and its culture, settled in Oahu in early 1907, after having traveled extensively throughout Asia and Siberia. Among his notable works from these theaters was his coverage of the building of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Arriving in the islands as a well-established author, the South Carolinian quickly went to work researching and writing about Hawaiian society.7 One aspect of native culture that particularly fascinated him was the sport of surfing. Like most people worldwide, he had never seen anything like it. To better under stand the sport, which at one time had been banned throughout Hawaii by New England missionaries who deplored its "immodesty and idleness," Ford sought to learn it.8

Ford's early attempts at surfing met with one failure after another. Nonetheless, he soldiered on, enlisting the paid assistance of local surfing instructors. Even that failed. He wrote, "It seemed to me that my teachers must give me up as an inept pupil, and they did." Ford's persistence paid off, however. As he continued his struggle to stand up on a board, a young surfer noticed his predicament and paddled over to assist him.It was George Freeth. Ford wrote, "A young hapahole (half-white, half-native) took pity on me. He was the champion surfer of the Islands." Ford wrote glowingly of his first meeting with the young Hawaiian, "I learned in a half an hour the secret I had sought for weeks."9

Their meeting in the waters off Waikiki proved fortuitous for both men. In Freeth, Ford found a kindred soul. The young Hawaiian' s polite, genteel manner matched his own cultured southern upbringing. More importantly, Freeth was very much like the author himself: restless, driven, and filled with an adventurous spirit. Ford would not only write of Freeth's skills on a surfboard to a worldwide audience, but he became so taken with the sport itself that he assisted in establishing the Outrigger Canoe and Surfboard Club on Waikiki Beach. He had two goals in creating the group. One was to encourage and preserve the sport among native Hawaiians. The other was to use the club's idyllic location, which fronted several beach hotels, to introduce surfing to visiting tourists.10 For his part, Freeth gave Ford's work credibility among the island population. Not only was Freeth respected and admired by locals on Waikiki Beach, his reputation was such that Hawaiian government officials selected him in May of 1907 to accompany a United States congressional delegation that was touring the Hawaiian Islands on a fact-finding mission.

Freeth acted both as a host and the delegation's chief lifeguard.11 Also joining the expedition, which was organized to determine if Hawaii could qualify for future statehood, was Ford. For years afterward, Ford used the tour and the connections he made on it as a political conduit to interest Washington in the territory and its peoples.

As the congressional tour continued to make its way throughout the island chain, Ford decided to remain behind in Waikiki.12 It was on Oahu that he made perhaps his greatest connection in publicizing the islands and his now-beloved sport of surfing. On the evening of May 29, 1907, Ford spotted fellow adventure writer Jack London and his wife, Charmian, enjoying a quiet drink in the foyer of the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. The southerner strolled over to the couple and introduced himself. At the time, London was arguably the most popular writer in the United States. To his good fortune, London was well aware of Ford's work and invited him to join them for dinner.13

While the two men discussed their various writ ing forays around the globe, it was Ford's talk of his latest project, which was to document and revive the ancient Hawaiian sport of surfing, that caught Lon don's attention. London was so captivated by the other author's description of the sport that he read ily agreed to join him on a "surfing excursion" in the waves off Waikiki Beach. Several days later, within sight of Charmian London, the two adventurers began to wade out into the breakers. Although Ford had greatly improved his skills on a board, he was certainly no expert, and preferred to surf on the smaller "inside" waves. However, far out in the dis tant surf, the two men spied George Freeth riding speedily across a large wave. Just as Ford had been when he first eye-witnessed surfing, London was enthralled. Mustering up their courage, the novices paddled out to join Freeth. London later wrote:14

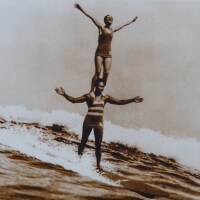

Shaking the water from my eyes as I emerged from one wave and peered ahead to see what the next one looked like, I saw him tearing in on the back of it, standing upright on his board, carelessly poised, a young god with sunburn. We went through the wave on the back of which he rode. Ford called to him. He turned an airspring from his wave, rescued his board from its maw, paddled over to us and joined Ford in showing me things.

Although London later suffered from severe sun burn and a bump on his head as a result of getting hit by a loose board, he wrote enthusiastically of his first experience surfing. He was also particularly taken with Freeth. Though the young Hawaiian was modest about his abilities in the ocean, London immortalized him and his water skills to readers worldwide. He wrote: "He is a Mercury-a brown Mercury. His heels are winged, and in them is the swiftness of the sea."15

As Ford and London continued to enjoy Hawaii, Freeth approached them for letters of introduction to take on a planned trip to California. Both authors happily complied. The three shared much in com mon: they were exceptional at what they did; all three enjoyed adventure; and all seemed to be afflicted with wanderlust. Now with introductions from the two notable authors as well as from members of the Hawaii Promotion Committee, whose purpose was to increase tourism to Hawaii from the mainland, Freeth boarded the San Francisco-bound passenger ship Alameda on July 3, 1907.

Freeth's departure from Hawaii was front-page news in the island's main newspaper, The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Under the banner "GEORGE FREETH OFF TO COAST - Will Illustrate Hawaiian Surfriding to People in California," the article, accompanied by a portrait of Freeth, detailed the twenty-three-year-old's contributions in reviving the once banned sport of surfing. The newspaper reported,16

At the time when Freeth first took up surf riding there had been very few here for many years who had been able to perform the trick of standing on a surfboard, and coming in to the shore on the crest of a wave. The white man who could do it was excep tional. Freeth determined that if the old natives had been able to do the trick there was no reason that he could not do the same. In a short time he mastered the feat and then went further. The older inhabitants told of natives in the early days who stood on their heads when they came in. Freeth soon proved that this could be done at the present time as well as before.

Three weeks after leaving Honolulu, Freeth was spotted surfing the waves off the southern Califor nia beach community of Venice. His appearance drew large crowds of onlookers. On July 22, 1907, a small news article with the headline "Surf Riders Have Drawn Attention" appeared in the Santa Monica-based newspaper The Daily Outlook17

The young Hawaiian's arrival in southern California could not have occurred at a better time. Los Angeles in 1907 was undergoing a large growth spurt both in population and business formation. Venice and Redondo Beach were center pieces of real-estate development along the region's stunning coastline. In May of 1904, cigarette magnate Abbot Kinney had announced a grandiose plan to develop a coastal resort community south of Santa Monica that would be modeled after Venice, Italy. Within twelve months, what had been derided by many in Los Angeles as "Kinney's Folly" had become a reality complete with scenic waterways, gondolas, and picturesque Italianate-designed buildings.18

Just a dozen miles to the south, meanwhile, Kinney's sometime business rival, Henry Huntington, was busy purchasing land in Redondo Beach.19 In July of 1905, he bought the Redondo Company, which owned nearly all the land in the quiet coastal town. "When I studied the place and saw its attractions," he remarked, "the beautiful topography it possessed, those terraces rising in harmonious degrees from the sea, I determined that it presented such features as should make it the great resort of this region."20 Very shortly, a three-story, Moorish style pavilion began to rise. Housing a massive second-story ballroom that could accommodate more than five-hundred dancing couples at a time, the 34,069-square-foot pavilion acted as a lure in attract ing visitors to his real estate interests in Redondo Beach.21 In addition, Huntington had solidified his investment in Redondo as well as his other substantial land holdings in southern California by developing what would become the region's dominant transportation system, the Pacific Electric Railway.

By 1907, both resort cities were attracting substantial numbers of visitors. Many of those who traveled aboard Huntington's big red cars to the coast fell in love with the beaches and their fresh ocean air. This, however, proved problematic for parents and children alike in that the inviting ocean they encountered at the shoreline could prove deadly for those who attempted to swim out among the waves. Recognizing the inherent dangers for those wanting to take "swims" along the coast, both Kinney and Huntington built swimming pools adjacent to their beach areas. Owing to the fitness craze sweeping the nation at the time, boosted in part by the very physically active President Theodore Roosevelt (1901- 1909), these warm salt-water pools were very popular with the beachgoing public.

Although the pools offered water recreation, the ocean was far more alluring for some bathers, especially venturesome teenagers. Many parents who once had considered buying coastal property did not, fearing that the attraction of swimming in the ocean would prove too tempting for their offspring. So dangerous were the waters that even experienced swimmers lost their lives at an alarming rate along the shores of Santa Monica Bay.22 Following the drowning deaths of two fishermen off Venice on May 12, 1907, both The Herald Examiner and The Daily Outlook wrote editorials condemning the lack of lifesaving equipment and trained ocean lifesavers along Santa Monica Bay.

Two months before George Freeth appeared surfing off the shoreline of Venice, Abbot Kinney, "The Doge of Venice," was appealing to residents to assist him in recruiting volunteer lifeguards. With her service group, The Pick d Shovel Club, Kinney's wife, Margaret, led a fund-raising effort to purchase a boat that could be used by lifesavers in the event of an ocean rescue. On May 28, 1907, the Venice Lifesaving Crew was formed with twenty-eight men volunteering their services.23 Sadly, only weeks later as the neophyte crew was practicing, a wave capsized the small two-man training dory, and volunteer life saver Charles Watson drowned in front of his stunned crew mates. According to The Daily Outlook, "Watson's drowning probably constitutes the most heartrending tragedy that was ever enacted within sight of the beach here and took place less than 400 hundred [sic] feet from where more than a score of the life corps stood, absolutely unable to in any way prevent his untimely death."24

The publication of the ocean lifesaving crew's inability to save one of their own spelled potential financial disaster for the growing beach tourist trade, as well as the region's coastal real-estate industry. However, the appearance of George Freeth in July 1907 marked the beginning of change. In Freeth, both Kinney and Huntington found a young man whose skill in aquatics drew crowds to their respective beaches. Moreover, his exceptional dexterity on the surfboard, which included standing on his head while surfing down a wave, tantalized beach going audiences as to what fun swimming in the ocean could be if they, too, could master Freeth's talents. It also helped that George was personable and intelligent. He possessed a warm and temperate nature that was ideal for teaching.

Within six months of his arrival in California, Freeth was commuting between the two seaside communities aboard Huntington's Pacific Electric Railway. At Redondo, in the employ of Huntington, Freeth performed his surf ing act twice a day under the billing "The Hawaiian Wonder."25 Along Venice's beach, meanwhile, Freeth did surfing exhibitions and worked with the volunteer lifesavers. At both locations, residents and visitors alike were captivated by the trans planted Hawaiian. For his part, Freeth understood the need to showcase his aquatic skills. He was savvy to promotion. With his surfing act he not only drew crowds to the beach locales but also to the plunges where he earned his living as a lifeguard and as a swimming and diving instructor.

Nevertheless, Freeth was not in the water-sport promotion business solely to make money. His real passion, which he approached with missionary fervor, was water safety. In the course of his work he selected and trained a group of young swimmers to become ocean lifeguards. Several of these would go on to form today's Los Angeles County, Long Beach, and San Diego Lifeguard Services. Freeth taught them such lifesaving skills as rescue swimming, ocean rowing, and paddling. The young neophytes were tutored by the gifted waterman in the art of using rip currents to help speed them out to swimmers in distress. Whereas other rescue personnel, particularly lifesavers on the East Coast, believed rip currents acted as an "undertow," Freeth demonstrated in his own rescue work that rip currents themselves do not drag swimmers "under," but instead out to sea. Freeth taught that fighting against powerful rip currents tired trapped swimmers and caused them to drown. Under his direction, then, his young proteges would enter the rip current, swim with it to the victim, and then guide the victim laterally out of the pulling current. This simple technique, which is still employed today, was responsible for saving hundreds of lives within its first five years of use.

Freeth did not stop there. Those under his tutelage, whether male or female, were expected to become "watermen." The young Hawaiian's vision of a true "waterman" was a person who was one with the ocean. Freeth expected his pupils, after dili gent training, to be able to safely swim, paddle, and row through treacherous surf. Additionally, he taught his future lifeguards the latest techniques and treatments in medical first aid. "Innovation" and "efficiency" were his watchwords; he encouraged people to think "outside the box" when it came to saving lives. Following his example, several of Freeth's pupils took up distance sand running, ocean swimming, and surfing to better acclimatize them selves to the rigors of the ocean from which they were now expected to protect swimmers.

Evidence of Freeth's devotion to swimming and lifesaving can be found in the careers of his follow ers. At Redondo, he nurtured several young swimmers, one of whom, Ludy Langer, would go on to set three world records. Discussing Freeth in a 1980 interview, Langer recalled:26

I remember George. You couldn't forget him. To see him in the water-well, I can't describe it. He had absolutely no fear of it. It was his natural place. There was something else about George-he was generous, generous to a fault. He coached I don't know how many of us-four of us went to the Olympics and he never charged us a dime.

Another Freeth protege was Redondo high diver Tommy Witt. He recalled, "I took my first dive from the rafters in the plunge when I was seven years old. I can remember Freeth's instructions and encouraging words. Freeth taught all of us kids confidence, style and fearlessness of the water."27

Freeth's own fearlessness played an important part in his work with the lifesaving crew at Venice. The death of volunteer lifesaver Charles Watson was a catalyst in promoting the need for a well-trained and amply equipped crew. Through large-scale fund-raising efforts, led by The Pick and Shovel Club, the Venice Volunteer Lifesaving Crew was able to purchase a sturdy metallic lifeboat that was built according to federal specifications. On August 24, 1907, with a large crowd in attendance, the new lifeboat was christened Venice with a bottle of champagne.28 Two and one-half months later a second lifeboat was donated by the Pacific Electric Railway Company.29 The acquisition of two lifeboats and a small mortar cannon-used to signal for help when a swimmer or boat was in distress-gave the Venice corps a boost toward professionalism. The equipment was nearly useless, however, without a well trained crew.

The federal government sent A.G. Humphries of the United States Volunteer Lifesaving Corps to give the men tips on rescue work, as well as to bring them under the agency's direction.30 But there was a problem with joining the national corps. The organization was designed to rescue boats and ships in distress, not swimmers caught in rip currents.31 For nearly a year, therefore, the Venice lifeguards elected to remain independent from the federal body.32

During this time, Freeth undertook to train the men in practical rescue work, which included not just the use of lifeboats, but also the novel idea of swimming out to bathers in distress. That was new. So grateful were the Venice guards for his tutelage that on the occasion of his twenty-fourth birthday, they surprised their captain with a gold watch and a card that read, in part:33

Mr. George Freeth, King of the Surf Board, Captain of the Venice Basketball team, First Lieutenant of Venice Volunteer Life Saving Corps, and leader in Aquatic Sports and General Good Fellowship, is reliable, sober, industrious ... We, his comrades and citizens of Venice, extend our best wishes and a watch, that he may continue to keep abreast of the time to the century mark at least.

As a further expression of their admiration for Freeth, the Venice Lifesaving Crew voted him their new captain at the annual year-end gathering and elections.34 This was a significant honor, consider ing that he had arrived in California just five months earlier.

Freeth's tireless efforts to make the Venice Volunteer Lifesaving Corps proficient at water rescue work were tested severely on the afternoon of December 16, 1908. On that day, at approximately one o'clock, a tremendous winter squall suddenly descended upon Santa Monica Bay. The usually placid waters turned quickly into rolling troughs of white caps and blinding spray. The gale force winds and the high surf they caused trapped several Japan ese fishing boats off the Venice Pier, near its protective breakwater. Although the crews fought valiantly to stay afloat and away from the pier's south-to north jetty of solid rock, the storm's immense strength proved to be too powerful.35

For the next two-and-a-half hours, George Freeth braved gale force winds, pounding surf, and a frigid ocean temperature to save single-handedly the lives of seven men. In the process he nearly lost his own life to hypothermia. Despite being near collapse from having stayed so long in the chilly waters, Freeth ignored the pleas of onlookers and dove off the Venice Pier to rescue still another boat in distress. It was his fourth time out on a long rescue. The Venice Lifesaving Corpsmen then risked their own lives and launched their boat to assist Freeth. Once the object of public ridicule, the now heroic Venice lifesavers rowed through the powerful breakers in the well-practiced fashion that Freeth had taught them. Inspired by the example of their mentor's tenacity in keeping three drowning fishermen afloat in the churning ocean, the lifeboat crew effected the final rescue.36 Freeth'sbravery, and that of the corps, was witnessed by thousands of onlookers, many of whom had left their jobs to watch the prolonged operation. Owing to Freeth's skills, and those of the crew he trained personally, not one life was lost in the ordeal.

Rescue of the eleven fishermen made front-page news in all of the major Los Angeles papers. Both The Los Angeles Times and The Los Angeles Tribune dispatched eyewitness reporters to cover the story.

Their first-hand accounts brought Freeth and his crew to national recognition. Ignoring the notoriety, the corps was back at work the next day. There they were met by the rescued Japanese fishermen, who presented Freeth with a gold watch and a financial donation.37 In addition, the grateful men announced that they had changed the name of their fishing village, located at the foot of the Long Wharf, in modern-day Pacific Palisades, from Maikura to Port Freeth. It bore that name until it was destroyed by fire five years later. A Herald Examiner reporter who visited Port Freeth in 1911 found that the villagers performed a nightly Shinto ritual, during which they burned incense and made offerings of rice and poi to honor the young Hawaiian responsible for saving seven of their own.38

In the days following the rescue, Abbot Kinney also visited the lifesaving station to thank Freeth. Besides his business interest as founder of Venice, Kinney had a personal reason to be proud of these men. His son, Sherwood, was a member of the lifeboat crew involved in the final harrowing rescue. Furthermore, Kinney and other leading citizens of Venice recommended Freeth for official commendation. In a sworn affidavit that was used to nominate Freeth for the Congressional Gold Medal, a witness declared, "In my opinion there is not another man on the beach, or perhaps in America, that could have accomplished the wonderful feat that Freeth accomplished in this matter." Another witness stated in his affidavit that Freeth received no salary for his services but worked purely on a volunteer basis. The same witness added: "There is no doubt in my mind that these seven men would have lost their lives on this occasion if it had not been for the noble efforts of this said George Freeth."39

As a result of these collected statements and the first-hand news accounts of the rescue, a special act of Congress dated June 25, 1910, awarded Freeth the nation's highest civilian honor: the Congressional Gold Medal. It was reported at the time that he was only the fifth recipient of the honor since George Washington first received it on March 25, 1776.40 Freeth and his crew were also recognized by the neighboring community of Pasadena, which invited them to participate in the 1909 Rose Parade. The proud Venice Lifesaving Corps marched alongside a small float, which they had dedicated to the profession of ocean lifesaving.41

The success of the 1908 rescue operation was tempered by the fact that the majority of the endeavor had been accomplished solely by Freeth. For more than an hour his fellow lifesavers were unable to lend assistance because they could not launch their lifeboat in the extremely high surf. By contrast, Freeth had managed to save seven lives that might otherwise have been lost, by the simple act of diving off the pier and swimming successfully through the powerful waves. His actions on that December day in 1908 ushered in a new era of ocean lifesaving. Whereas before then lifesavers wasted precious time assembling crews and waiting for the right moment to launch their crafts, the new practice demanded dispensing with boats in favor of swimming out immediately to those in danger, regardless of weather or the size of the surf.

Freeth played the key role in revolutionizing the way lifesavers performed their work. Both by example and reasoning, he emphasized the need to handle rescues in a completely different manner. When proponents of lifeboats argued that lifesaving crews could make rescues much farther from shore and carry more victims than a swimmer acting alone, Freeth pointed out that rip currents closer to the beach were far more likely to place people in distress. He was correct. As times changed, and more and more swimmers abandoned Victorian modesty to venture into the ocean clad in one-piece bathing suits specifically designed for swimming activities, older rescue methods became outmoded. After all, the original lifesaving boats and their crews used in America since colonial times were intended to save ships in distress, not recreational swimmers. By 1908, corps members realized that assembling a lifeboat crew to rescue a distressed swimmer just fifty yards offshore was nothing short of foolishness. They also recognized the inherent problems with use of lifeboats, especially their tendency to flip over in high surf.42

Central to Freeth's contributions was the way he taught lifesavers to perceive themselves and their work. During his tenure along the southern California coastline, the term lifesaver was abandoned in favor of the title lifeguard. To George, an ocean lifeguard was "at one with the water," being proficient not only in ocean swimming, but also in row ing and surfing. In Freeth's vision, the concept of lifesavers, whose primary mission was to respond to someone in distress, would be replaced by life guards, whose purpose was focused primarily on preventing situations where rescues became necessary. In short, where the traditional view of lifesaving was reactive, Freeth's view of lifeguarding was pro-active. According to this new perception, guards would patrol area beaches constantly in order to warn swimmers away from ocean-related dangers such as inshore holes and rip currents.43

Freeth worked diligently with his crewmen to improve their swimming skills for lifeguarding. While swimming competitions remained popular among the guards and the public at large, Freeth found that many swimmers deplored the drudgery of year-round training, with the consequence that they often skipped workouts during the winter months. To encourage swimmers to stay in shape, Freeth helped organize the relatively new sport of water polo.44 It quickly became popular with the guards and served to keep many of them physically fit through out the year. Freeth himself competed, playing at various times for the Venice and Redondo Beach water polo clubs. Before long, he garnered a reputation as the best water polo player on the West Coast.45

In the summer of 1909, Henry Huntington opened an opulent new "plunge" in Redondo Beach. Located south of the Moorish Pavilion, the new $200,000 natatorium, Redondo Plunge, looked more like a royal palace than a public swimming pool. Advertised as the "largest in the world," the three-story structure occupied 43,688 square feet of beachside property. With over one thousand dress ing rooms and three heated pools, the Redondo Plunge could hold as many as two thousand swimmers at one time. It was here that Freeth spent much of his time lifeguarding, teaching, and per forming. L.E. Martin, who developed water rescue equipment with Freeth's advice, recalled the latter's popularity:

He had a native wit which sent waves of laughter through the house and his step and stride were that of an aristocrat of strength. His skill in diving was an art of unsurpassed beauty and when you see him come down from an 86-foot stand, or spring into a lifeboat, you marvel that 170 pounds can, at all times, move with such perfect grace.

So popular was Freeth with plunge visitors, in fact, that when he suffered a small bout of food poison ing, local newspapers carried the story.46 One woman who attended the plunge on a regular basis wrote The Redondo Reflex stating that "Many visitors to the beach have wished for an opportunity to express appreciation for the work of Mr. Freeth at the bath house. We have been entertained by his wit," she continued, "rejoiced by his chivalry, inspired by his courage and awed by his sublime heroism. Redondo Beach is fortunate to have in her midst a teacher of aquatic expertise who is so perfectly the exponent of that what he teaches. Long may he live – this large souled, fine grained, noble hearted Freeth."47

Whatever satisfaction he might have derived from performing, competing, and lifeguarding, Freeth's greatest enjoyment at the Redondo Plunge seems to have been his work with young people. He spent much of his time turning his pupils into well rounded water athletes who could surf, ocean swim, and compete at water polo. Free from many of the prejudices of the day, Freeth also heartily encouraged women to participate. One of his favorite students was Dolly Mings, whom he taught to swim. With his patient tutelage and her strenuous conditioning, she developed into a world-class swimmer. In fact, within three years of her first lesson with Freeth, Mings set the national record in the women's fifty yard freestyle.48

Among Freeth's other responsibilities at the plunge was responding to the needs of distressed bathers in the adjacent ocean. Newspapers such as The Redondo Reflex and The Redondo Breeze actively carried stories of such rescues. Summoned by the ringing of emergency bells placed along the shoreline or by the phone at the new plunge, Freeth would rush out of the building and down the beach to rescue whomever was in need.

With increasing popularity of ocean swimming, and as the swimming beaches grew longer in length, the resourceful Freeth began devising new methods to handle the growing needs. First and foremost was his work in creating the Redondo Beach Lifesaving Corps. Freeth staffed it with many of his young swimmers, including world-class athletes Ludy Langer and Cliff Bowes, both of whom were able to swim out to swimmers in need of rescuing.

For lifeguards who did not have strong swimming capabilities, or who tended to tire during a long return to the shore against the pull of a wide rip cur rent, Freeth developed a large rescue reel with the assistance of Byron Minor, the manager of the Redondo Plunge. Set on a large triangular pod, the reel held 1,500 feet of cable. Attached to the cable was a torpedo-shaped rescue buoy. When a lifeguard entered the water with the new buoy, he could effect the rescue and then be reeled in, together with the saved swimmer, by his fellow guards.49 A year later, while area fire departments still used horse-drawn carts to transport emergency equipment, Freeth combined his innovation with motorcycle technol ogy to allow greater mobility. Specifically, he devised a rescue sidecar attached to a motorcycle, which he provided with a smaller version of the reel and its metal rescue can. The new device, financed by local officials, was an immediate hit. Each morning Freeth warmed up the motorcycle and then patrolled the South Bay beaches. He assured local residents that once he received an alarm call, he could be on the emergency scene within three minutes.50

Despite his successes at Venice and Redondo Beach, Freeth, like other lifeguards of that era, was plagued by low wages. In September 1910, accompanied by two other West Coast lifeguards, he returned to his native island of Oahu, where he secured work as a deep-sea diver to construct dry docks at the rapidly growing port of Pearl Harbor. When not working, Freeth could be found surfing or playing water polo. His return to Hawaii was well-publicized by The Pacific Commercial Advertiser and subsequent news of him often noted his having been awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

In January 1911, Freeth returned to Redondo Beach, where he was rehired at his old job and for mer salary at the plunge. The low pay he received for his work became a concern for Redondo Beach officials.51 Fearing Freeth would leave Redondo Beach and seek employment elsewhere, town fathers added to his regular wages by hiring him as a "special lifeguard," giving him extra work helping to res cue distressed swimmers along the neighboring beach, at $25 per month.52 Adding to his woes was a ruling by the national Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) that those who received compensation for aquatic activities would be prohibited from competing in the approaching 1912 Olympics at Stockholm.

In July 1913, George's good friend Duke Kahanamoku visited him at the plunge. One year earlier, Duke had shocked the sports world with his record-breaking time in the 100-meter freestyle event, and from that he attracted an enormous following. To the delight of the crowd, Kahanamoku and Freeth, along with several other visiting Hawaiians, went out surfing. When reporters later asked the Olympic champion to discuss his experiences at Stockholm in 1912, Kahanamoku complained that the United States would have dominated the Olympic diving events if his fellow Hawaiian, George Freeth, had been permitted to compete. Duke ranked Freeth "the world's greatest diver."53 On September 12, 1913, Freeth and Redondo life guard George Mitchell were involved in a motor cycle accident en route to an ocean rescue. Suffering a broken ankle, George was unable to work. As a result of the financial strain this placed on him, he moved from a boarding house to reside in the Mitchell family home.54 During this convalescence, Freeth accepted the position of head swimming instructor at the prestigious Los Angeles Athletic Club.55

From October 1913 to February 1915 Freeth worked at the downtown club, giving swimming lessons and coaching the swim team. The LAAC, as it was known, had among its members many of Los Angeles's most powerful and influential business leaders. These included his former employers, Abbot Kinney and Henry Huntington. George's arrival at the LAAC was the turning point for the club, which developed one of the country's top swimming pro grams under his direction. Its roster eventually included Olympic swimming gold medalists Johnny Weismueller and fellow Hawaiian Clarence "Buster" Crabbe, both of whom later acted in Tarzan films. As the new LAAC swim coach, Freeth brought with him several of his young proteges from Redondo Beach, such as the future world record-holder in swimming, Ludy Langer, and the Pacific Coast div ing champion Cliff Bowes. In October 1914, Duke Kahanamoku joined the team. Under Freeth's guidance, Duke improved both his free-style stroke and his open turns.56 Although the 1916 Olympics were canceled due to World War I, Kahanamoku won two more gold medals when the games resumed in 1920. At that date, he was considered to be the world's greatest swimmer. Also taking medals in 1920 were two other athletes formerly coached by Freeth, Ludy Langer and Ray Kegeris.

Among Freeth's most important contributions while working at the LAAC were the articles he wrote for the club magazine, the Mercury. Influential subscribers read of his desire to create a year round, professionally paid ocean lifeguard service. He also penned several articles on lifesaving and the need for local schools to incorporate swim lessons into the curriculum.

In 1915, the increasingly prominent San Diego Rowing Club approached Freeth to take charge of its expanding swim program. Much like the LAAC in Los Angeles, the membership of the Rowing Club included local politicians and civic leaders.57 Freeth accepted the offer and relocated southward. Within two months he transformed the Rowing Club's aquatic program to match what he had accomplished in Los Angeles. So successful were his efforts that by 1919, the club's once undistinguished swim team had become the pacesetter in California. During summer months, he supplemented his income by working as a swimming instructor and pool supervisor on Coronado Island, adjacent to the famous Hotel Del Coronado. He also gave spectacular diving performances, which were lauded by the local media. Despite his great reputation, he still struggled financially. His position worsened considerably when on September 14, 1916, the board of the Rowing Club voted not to continue his employment, owing to a shortage of funds.58 The board did allow him to stay in the club's facilities when his financial situation deteriorated in the fall of 1917. Even that, however, proved temporary. Two days after Christmas the directors canceled Freeth's sleep ing privileges and use of the captain's room at the club house.59

Faced with deepening financial difficulties over the winter months – a condition common to weather-dependent lifeguards – Freeth took a job at San Diego's Cycle and Arms Company, which was owned by a sympathetic Rowing Club member. He moved into the downtown Southern Hotel, and continued to work out at a nearby YMCA hotel in order to prepare himself for a rigorous summer sea son back on Coronado Island.

Freeth's position at the sporting goods store was certainly a disappointment for him. All of his life had been centered on the ocean. It was a medium in which he thrived and from which he had gained considerable fame. But as a salesperson, he lost much of the status he had enjoyed while working along the beaches of Venice and Redondo. No longer the captain of a local lifesaving corps or fully employed as a world-class swim coach, Freeth bided his time at the store while awaiting the return of summer, when he could once again showcase his lifesaving and surfing skills.

As he continued his sales work, Freeth witnessed firsthand the growing impact of World War I on the city of San Diego. In the spring of 1918 the U.S. Army began a crash program to enlist and train one million service personnel. Military bases throughout the area were quickly filled with combat trainees. Many of the new arrivals, when given leave, visited the region's scenic beaches. As the weather improved, thousands of servicemen could be found sunning themselves along the local shoreline.

On the first weekend of May 1918, San Diego was enveloped by a spring heat wave. Large crowds descended on the beaches, where lifeguard protection was minimal at best. On the first Sunday, strong rip currents began pulling off the shoreline of crowded Ocean Beach. Within view of thousands of spectators, several swimmers found themselves being dragged out to sea. Soon tiring, they began screaming for assistance. Without a professional lifesaving corps in place, the victims drowned. At the risk of their own lives, several military person nel went out into the treacherous surf to assist, only to suffer the same tragic fate of those whom they had sought to aid. When the disaster unfolded, thirteen men had lost their lives.

On Monday, May 6, shocked San Diegans, as well as military personnel, called for a full investigation into the deaths. At a quickly convened coroner's inquest, a twelve-member jury blamed the "unusual conditions of tide and currents prevailing on that day" for the thirteen drownings.60 In truth, the tidal conditions on that section of beach were not at all unusual; it was and remains today an area subject to strong rip currents.

Promoters of Ocean Beach were well aware of their resort's inherent dangers. Fearing financial ruin, however, supporters continued to publicize the small town and its recreational amenities. In fact, just six days after the tragedy, the Ocean Beach Advertising Club announced a $2,000 buried-treasure hunt along the shoreline.61 Publicists also advertised that new lifesaving measures were being implemented to provide complete safety for the swimming public. Chief among the changes made was the hiring of George Freeth as the area's lifeguard.

On May 19, 1918, Freeth was back at work and, ever resourceful, he brought with him his large tripod rescue reel. The "New Life-Saving Device" was given heavy publicity by The San Diego Union. To further assist his work, Ocean Beach officials paid for a motorcycle and sidecar, which Freeth used as his emergency vehicle along the strand.

Now in the employ of the resort owners, Freeth not only provided lifeguarding services, but again demonstrated his surfing abilities to the crowds who visited the area's bustling boardwalk and crowded sands. One newspaper article reported:62

Four thousand beachgoers received a surprise and enjoyed a succession of thrills and healthy laughs yesterday at Ocean Beach when George Freeth, life guard, presented his unannounced surfboard dive. Riding on the crest of the wave in the usual manner, Freeth suddenly leaped clearing the board by at least three feet, turned a somersault, regained his balance on the board again, then completed his stunt with a dive. The trick was a thriller, and evoked a storm of applause.

By the summer of 1918, Freeth was at the top of his form. Large crowds flocked to the beach to enjoy his surfing exhibitions. More importantly, under his watchful eyes and those of the lifeguards he commanded, not a single swimmer drowned.63

As Freeth guided his crew through a success ful summer season, local military officials contended with a severe base housing shortage. With the country fully involved in World War I, San Diego continued to be a leading training cen ter for new recruits. It also became a major convalescent center for veterans injured in the conflict. When several bases filled beyond capacity, commanders were forced to house service personnel in local public buildings. In these overcrowded conditions, the spread of infectious disease became increasingly commonplace, most notable of which was a new deadly strain of influenza. The subsequent Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 was the worst in the history of the United States. It killed more Americans in a single year than the combined United States combat deaths in two world wars. Globally it killed over twenty million people.64

The disease was particularly deadly for American servicemen. Over 40 percent of navy and 36 percent of army personnel became afflicted with it.65 San Diego was especially hard hit because of the heavy concentration of servicemen. The virus also spread so quickly outside military bases there that three weeks before Christmas, health department officials enforced a city-wide quarantine.66 But it was to little avail. Despite the widespread wearing of flu masks by the public, the crisis did not abate. In a cruel twist of fate, the virus often struck those in their prime of life: individuals in their twenties and thir ties. On January 15, 1919, thirty-five-year-old Freeth contracted the disease.67 In excellent shape before the onset of the malady, he weathered the first attacks of the virus. Often bedridden, and now unemployed, his financial situation grew steadily worse. To swimmers and lifesavers alike, word was sent up and down the California coast that he had taken ill with the virus. A collection was organized by his former employers at the San Diego Rowing Club and money for his support began to pour in.68

In late March of 1919, The San Diego Union reported that for the first time, the relapsed and hospitalized Freeth was encountering reverses in his recovery. Ludy Langer, who had just returned from fighting overseas, went to visit him. Officials of the Agnew Sanitarium where Freeth was undergoing treatment refused to admit him. However, Langer persevered and was allowed to see his ailing mentor. Langer recalled, "He was very ill and didn't say much." But, he added, when the two men talked "of the old days...once or twice I got a smile out of him."69

Late on the evening of April 7, 1919, Freeth died. News of his demise appeared in several leading California newspapers where obituaries recalled his life saving exploits and his prowess at swimming, diving, and surfing. A well-attended funeral was held five days later at a local mortuary chapel. Since the Freeth family was unable to travel from Hawaii, his mother's wishes to have George cremated and returned to his native Oahu were honored by the San Diego Rowing Club.70

When George Freeth first arrived in California he had little more than a suitcase with him. When he passed on, what he had in the way of worldly goods could be placed in the same suitcase. Freeth was never a man of money; instead he was a man of deeds.

Freeth's greatest virtue was his willingness and ability to teach and share the exceptional talents that he possessed. His generosity, integrity, and kindness influenced all of those around him. In an age when the ocean was to be feared and avoided, George Freeth introduced surfing to southern California. To the delight of large crowds gathered along local beaches, Freeth demonstrated the sport that he would later gladly teach, without pay, to area youngsters. It was from these warm California coastal waters that surfing would ultimately gain its great est appeal amongst the American masses.

Freeth also worked diligently to teach and popularize the aquatic sports of swimming, water polo, and diving. His legendary status in each of these activities did not prevent him from sharing his know-how and imparting his skills to his students, including several divers and swimmers who achieved national and international prominence.

Freeth's greatest impact on California, however, remains his instrumental role in revolutionizing the profession of ocean lifesaving. Before his arrival, a few volunteer lifesavers utilized ocean safety skills that focused on the use of lifeboats and rowing crews to save individuals from drowning. Adapting to changing times, local conditions, and new technologies, Freeth preached and practiced the importance of quick action to carry out rescues. As importantly, and as a lasting legacy, many of the young swimmers under his guidance became the future nucleus of today's ocean lifeguard services in California. As a result of Freeth's innovations and the standards he established, drownings on modem guarded beaches in California have become extremely rare.

Although George Freeth's "passage," as Hawaiians call the period between birth and death, was short, it was nonetheless full. From the shores of Hawaii to the sands of California, George Freeth touched thousands of lives for the better. Fulfilling the true calling of a hero, he repeatedly risked his own life so that others could live. His individual courage and personal actions on behalf of those in great danger stand as a final testament to a true, but often forgotten, hero of California history.

Jack London, with his typewriter, first brought George Freeth to the world's attention. He penned these prophetic words that would apply not only to his own short life, but also to that of his Hawaiian friend:

I would rather be ashes than dust. I would rather that my spark should bum out in a brilliant blaze than it be stifled by dry rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The proper function of man is to live, not to exist.