From Hiking to Hospitals: L.A. at the Center of the Pursuit of Health

Editor's Note: Sanatorium, sanitarium, and sanitorium were used interchangeably in the marketing of wellness in Los Angeles. In this essay, sanitarium is used consistently, except where sanatorium was used as part of an institution's name.

An unseen miasma drifted through the 19th century in the hallways of crowded tenements and through teeming city streets. It brought a persistent cough at first, exhaustion and lassitude later, then bloody sputum and finally a lingering death. Delicately referred to as "consumption," it was properly called tuberculosis.

The disease killed one in seven Americans. Its true cause was unknown. There was no cure, only exile from family and home in a relentless search for relief.

Benjamin C. Truman, former Chief of Literary Bureau for the Southern Pacific Railroad, told sufferers that only one place in the West held the possibility of healing. Because of its miraculous climate, Los Angeles was destined to be "the sanitarium of the Union."

Contagion was unknown in the radiant sunshine. Even the air was magical. It gives, Truman wrote in Semi-Tropical California in 1874, "a stimulus and vital force which only an atmosphere so pure can ever communicate."

"Remarkable, indeed, is the record of cures wrought by this wonderful climate," enthused another tourist guide from 1889. "Consumptives, whom physicians of the East had declared past all help have come here, and in a few weeks have shaken off the fetters of that Eastern ice-born curse."

Between 1870 and 1920, city boosters, real estate promoters and physicians (both legitimate and crackpot) gave the unwell hope and gave the world an image of Los Angeles that was mostly illusory. As Emma Adams marveled in her 1887 sketch of Los Angeles, there "every thing is new and peculiar and wonderful." Los Angeles became a city of impossible dreams with the pursuit of health.

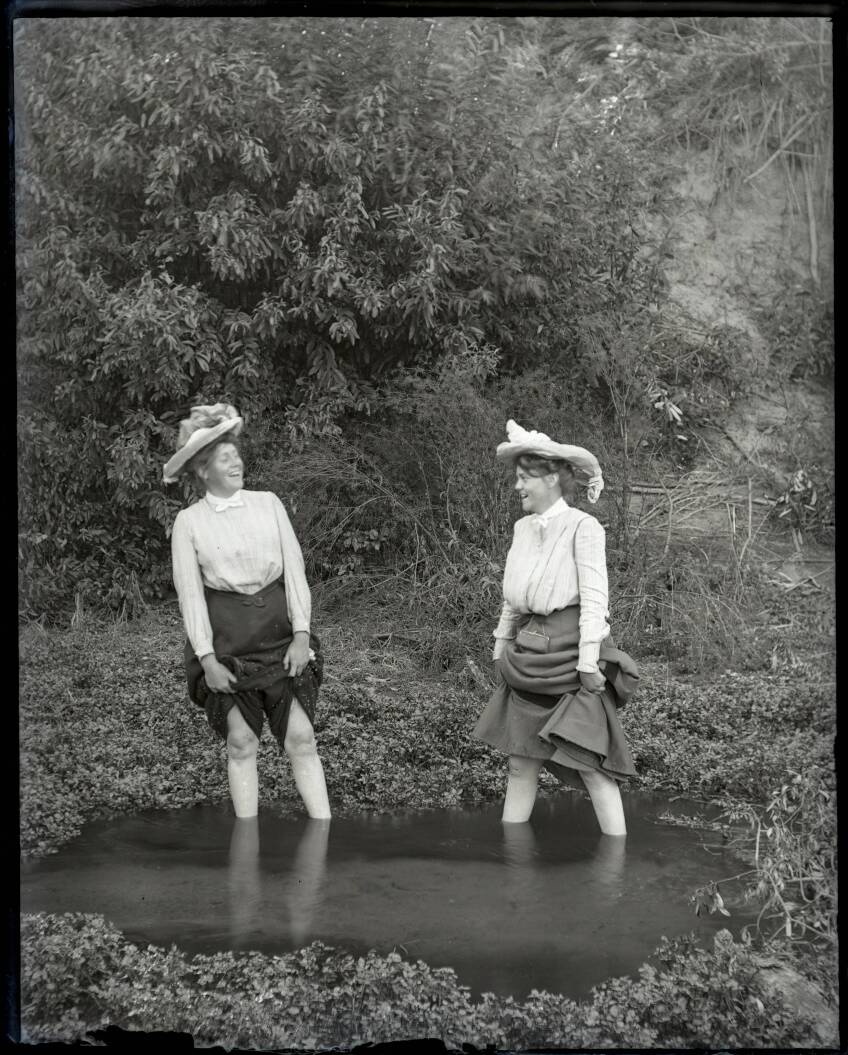

Doctors Widney and Orme, on behalf of the county medical society, laid out a table of diseases for which the geography of Los Angeles was the remedy. For the worried well with a "delicate constitution," Boyle Heights was a comfortable retreat. Consumptives in the early stages of the disease might be made whole after a "rest cure" in the foothills of the San Gabriel Valley. And "cases of nervous prostration" or "an overtaxed or deranged nervous system" would be restored by an active, outdoor life anywhere in Los Angeles "on account of the remarkable tonic qualities of its atmosphere."

They came — the "tuberculars," the debilitated Civil War veterans and those who failed to thrive. An estimated 25% of migrants who arrived before 1900 did so as invalids. They were an essential part of a wellness economy where, one commentator noted, "men go not to buy land but to buy lungs."

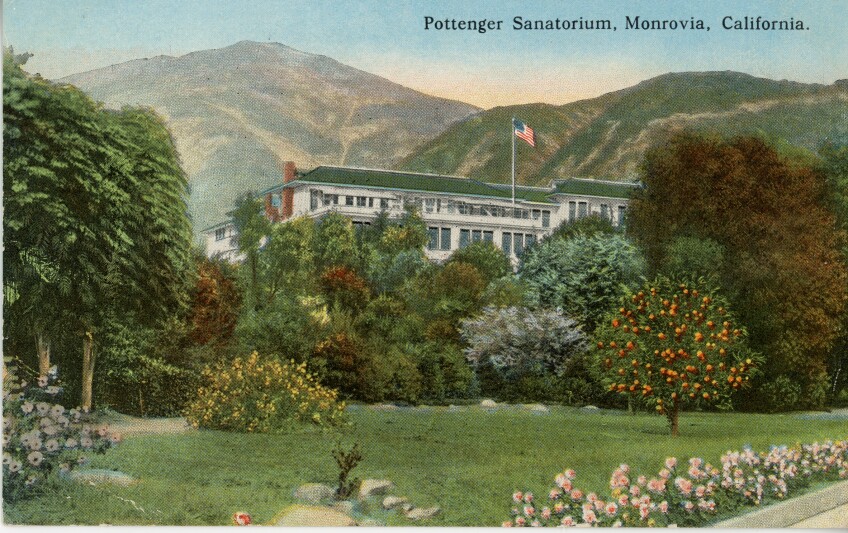

By 1910, a "sanitarium belt" extended along the front range of the San Gabriel Mountains from Altadena through Sierra Madre to Glendora to receive tubercular patients from "back East." By day, they lie on wicker lounges, lined up on wide verandas, and ordered to be indolent under a strict regimen: no alcohol, no smoking, no cursing, no intercourse. Patients might stay for years, occupied with crafts, writing for the sanitarium newspaper and thinking positively.

Some sanitariums were run like resorts. Some experimented with exercise cures. A few were "health farms" where patients slept in canvas tents that were hardly more than open-air platforms. The treatments could be dubious: Marathon Bio-Bloodwash Baths and irradiated water called "liquid sunshine." William Ray Simpson, operator of the Long Beach Sanitarium, combined exposure to bolts of static electricity with a bland, meatless diet.

The best sanitariums were under the direction of a charismatic doctor, often one who had restored his own health in the climate of Los Angeles. Dr. Francis Pottenger based his Monrovia sanitarium on European models and dosed his patients a cocktail of fruit juices and castor oil. Dr. Walter Barlow cared for those unable to afford treatment at his sanitarium on the slopes of Chavez Ravine, as did Dr. Henry Stehman at the La Viña Sanatorium in Altadena.

Banker Kaspare Cohn set up a small sanitarium for the Jewish Consumptive Relief Organization in Angelino Heights. After several relocations, Cohn's sanitarium became the City of Hope in Duarte.

Its move was a symptom of resistance to the "busted lung brigade," whose members had become less wealthy and less white by 1900. Tuberculosis was now known to be communicable, and a new fear — contact with a "tubercular" could be deadly — turned sufferers into menaces. Hotels, resorts and restaurants posted signs refusing service to those with the disease. Sierra Madre incorporated in 1907 and immediately banned new institutions "for the care and treatment of mental, contagious, or pulmonary diseases" to dispel reports "that this city is nothing but a big consumptive camp."

Los Angeles used new zoning authority to separate sanitariums from homes, schools and churches. The Chamber of Commerce worried that that Los Angeles had sold itself too successfully as a place where invalids waited to die in the pure air and perpetual sun.

The Chamber of Commerce worried that that Los Angeles had sold itself too successfully as a place where invalids waited to die in the pure air and perpetual sun.DJ Waldie, writer

Those influences were still potent — but sun and air would be marketed in the 20th century to the already healthy, hoping to become even healthier.

Richard Neutra's Demonstration Health House, built for the physician and naturopath Philip Lovell, was designed in 1927 for hygienic living and nude sun bathing.

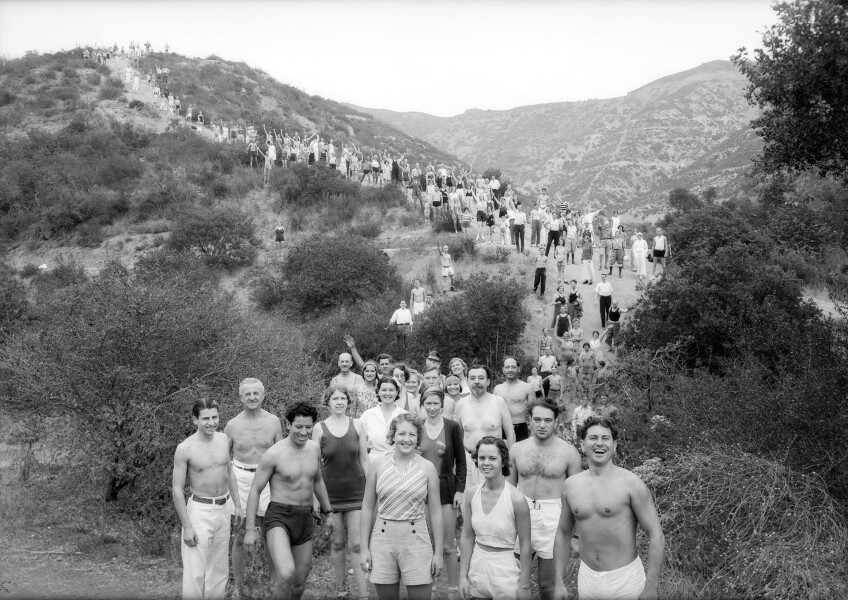

Fitness enthusiast Paul C. Bragg urged hikers he called his Wanderlusters to join him on day-long tramps through Altadena's Millard Canyon and up Griffith Park's Mount Hollywood. Hundreds of sun-seekers followed him.

Some looked to the hills for enlightenment. Charles Francis Saunders thought that in the "wild, majestic solitude" of the nearby mountains and deserts the "the veil between this world and the spiritual seems thinner than elsewhere … the awakened soul hears the summons to a new life."

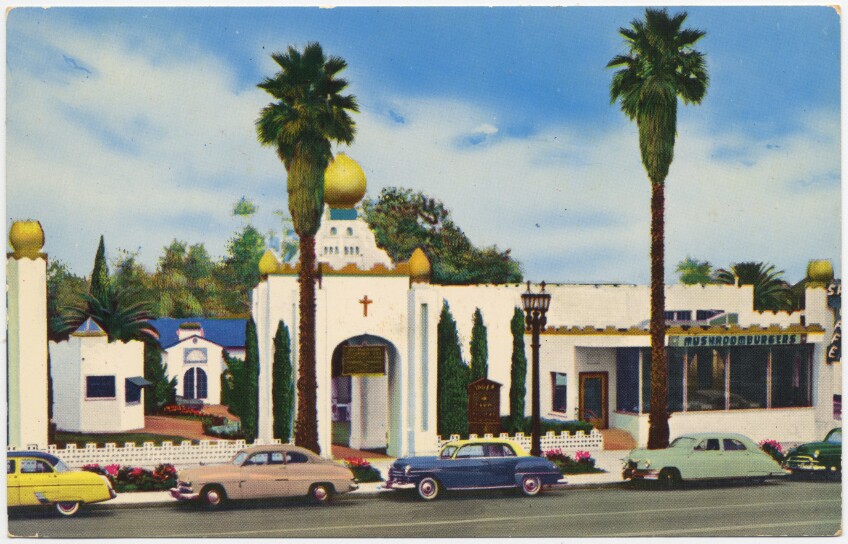

Swami Paramhansa Yogananda told the crowds that attended his talks that the sacred landscapes of Kashmir were reborn in Los Angeles. Mount Washington would become a place of pilgrimage.

Yogananda packaged traditional Hindu theology and spiritual practice in the context of 20th-century aspirations for wellness and personal development. His yogic techniques, he said, recharged "the body batteries with fresh life current" by increasing something he called "dynamic power of will." The goal was "Scientific Spiritual Realization" — but Yogananda also included spontaneous healing and recollection of past lives among the benefits.

Yogananda was one of many swamis, gurus and pandits — some genuine, some fake — who evangelized Los Angeles in the 1920s. The city was a "spiritual frontier" where a spectrum of beliefs — Theosophy, Vedanta, Christian Science, Aimee Semple McPherson's fundamentalism and Pentecostal revivalism — competed with the actual charlatans who advertised transcendence in the Saturday edition of the Times. What had been new and wonderful in 1887 increasingly seemed merely eccentric to the rest of the nation.

Angelenos' embrace of health foods (which Bragg promoted), colonic irrigation, radium baths, astral projection and conversations with "ascended beings" branded the city as an absurd place mocked by H. L. Mencken, Christopher Hitchens, Truman Capote and Kate Braverman, among many others. Even the architecture, according to author Nathanael West, was deranged.

For critics, the climate that defined Los Angeles and its inhabitants had become more sinister than the miasmas that supposedly bred consumption. "The palm trees have been brought in, the poor dears," lamented Dorothy Parker in a 1953 edition of Seven Arts Magazine, "they died on their feet. Brilliant flowers smell like old dollar bills. Those enormous vegetables taste as if they had been grown in old trunks."

In his 1954 short story "Golden Land," William Faulkner deplored the cult of health:

[T]he bathers passed: young people, young men in trunks, and young girls in little more, with bronzed, unselfconscious bodies … precursors of a new race not yet seen on the earth: of men and women without age, beautiful as gods and goddesses, and with the minds of infants.William Faulkner, "Golden Land" (1954)

The signs of Angeleno wellness had become emblems of the strangeness of Los Angeles. Unmoored from the seasons, unregulated by cultural elites, seekers with unreliable compasses, Angelenos could be dismissed along with their city and its enervating climate.

Behind the ridicule was something darker. If the city's gaudy ballyhoo of insistent sunshine and self-realization should end, the critics said, there would be nothing left but the "façade-ness" of Los Angeles, sketchy and insubstantial, at best a sideshow attraction, and ultimately perverse. Everything that had once promised physical and spiritual transformation rendered Los Angeles unfit to be an authentic place.

Instead, as author Pico Iyer has said, unreal Los Angeles had never been more than a "space waiting to be claimed by whatever dream or destiny you wanted to throw at it."