"Elysian Park is Their Playground": How Grace Simons Saved One of L.A.'s Oldest Parks

When Grace E. Simons relocated to Los Angeles from New York in the early 1940s, she and husband Frank Glass settled into a little house on Morton Avenue, two blocks from Elysian Park. Over the next twenty years, Simons dedicated herself to a busy career as an editor and journalist, first at the Los Angeles Sentinel, and, later, the California Eagle. She spent much of her free time gardening and enjoying strolls in the nearby park, especially upon her retirement in the early 1960s.

So when in March 1965 the L.A. City Council approved a plan to build a convention center and exhibition hall on 63 acres of Elysian Park – and not just any 63 acres, but the park’s most popular valley and picnic grounds near the Avenue of the Palms – Simons found it simply unacceptable that the Council viewed park space as “merely…[land] ‘in storage’ to be used for other purposes at the whim of…city officials.”[1] Although she had been a lifelong political activist, conservation was a new issue for her – but one important enough to spring her into action. To Simons, this beloved park was irreplaceable.

The proposal’s timing seemed perverse, given that it came less than a year after the California state legislature allocated over $4 million to L.A. County for acquisition and improvement of public parks under the 1964 California Park Bond Act. In response to the legislation, the City Council’s Recreation and Parks Committee outlined a strategy for creating new parks and improving older ones, a necessity in a park-poor city with a rapidly increasing population. These facts made it all the more perplexing that the City Council and Mayor Sam Yorty would endorse a proposal to destroy 63 acres of prime parkland.

The proposed convention center’s design offered very little in the way of architectural innovation. Yet a convention center would have made a stunning impact on the Elysian Park landscape. If the project had followed through with promised upgrades to the park’s design and facilities, the park might have become more widely used by L.A. residents. More likely, however, is that the destruction to the park’s landscaped picnic areas and increased traffic would have had a detrimental effect on park users and nearby neighbors. Any future expansion of the convention center would have further eroded parklands and exacerbated traffic congestion.

Prior to 1965, Elysian park’s status as city-owned property left it vulnerable time and again to municipal officials seeking “free” land for specific projects.

Elysian Park is located just outside downtown Los Angeles, adjacent to the 5 and 110 freeways. The park hugs Dodger Stadium on three sides, and both the 110 freeway and the Stadium Way thoroughfare run directly through the park. The park’s 575 acres boast landscaped picnic and recreational spaces, steep hills, rocky terrain, deep ravines, and overgrown hiking paths, as well as stunning views of the Los Angeles basin.[2] Founded in 1886, Elysian Park was protected by the 1925 city charter, which guaranteed all designated parkland would remain in “perpetual public use.”[3] But the park has been plagued by neglect and underuse, aggravated by inconsistent funding and public policy that prioritized playgrounds and recreation over tranquil landscaping.[4] Prior to 1965, Elysian park’s status as city-owned property left it vulnerable time and again to municipal officials seeking “free” land for specific projects in order to minimize fiscal impact.[5]

After World War II, encroachment on public parkland was aided by federal urban renewal policies that sanctioned condemnation if the land was needed for a "public purpose" such as highway construction. Elysian Park was one of many L.A. parks that lost acreage to highway construction, which brought air and noise pollution “uncomfortably close” active recreation areas.[6] Elysian Park also lost roughly 30 acres to Dodger Stadium, which reinforced the view that park space was merely undeveloped land that could be successfully appropriated by the city for non-park purposes. The adverse effects of the stadium’s construction included damage to Elysian Park’s irrigation system and the development of six-lane Stadium Way drive, which brought high-speed traffic through the park’s most popular valley.[7] Despite the challenges posed by traffic and neglect, residents from nearby Latino and Asian communities continued to heavily patronize the park.

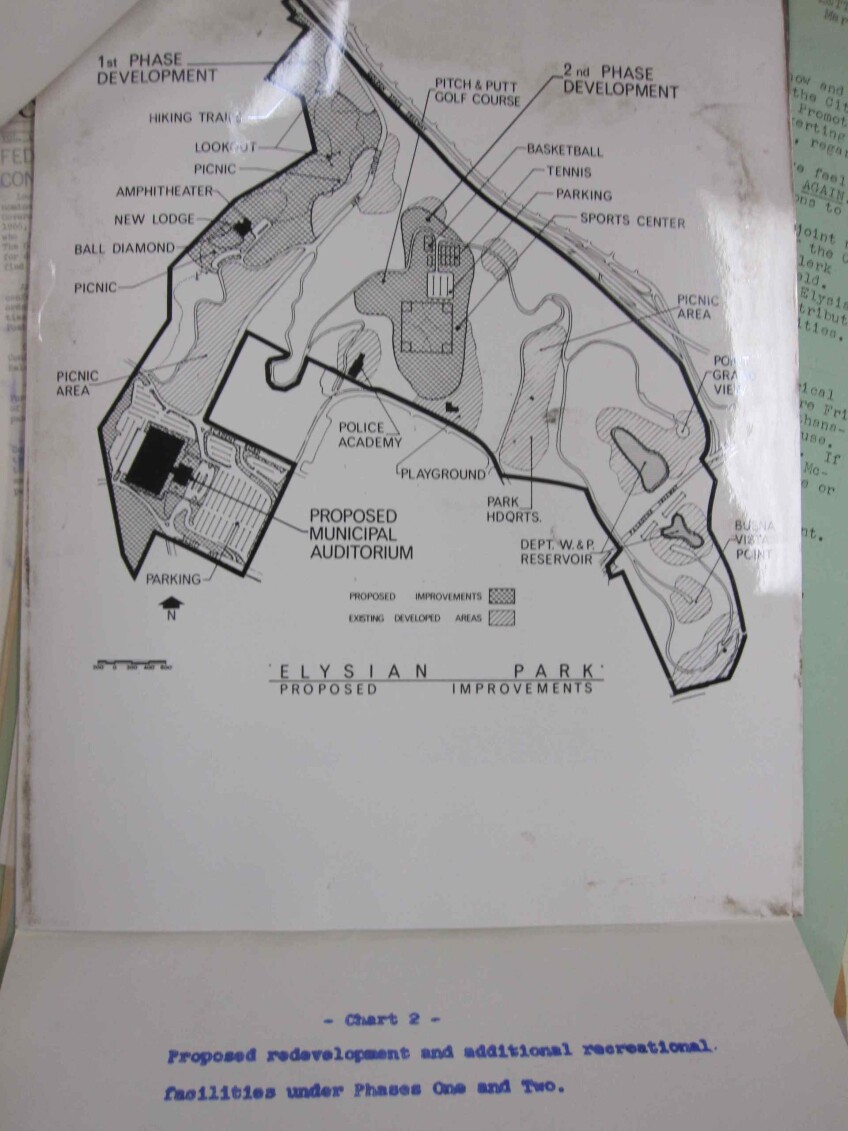

Elysian Park was targeted as an attractive location for the convention center, in part, because it was seen as less expensive than other options. The City Council set a $10 million limit for the project. Because Elysian Park was municipally owned, it would save the city from land acquisition expenses and costly eminent domain proceedings needed at other potential sites.[8] Surprisingly, the city’s Recreation and Parks officials heartily approved the convention center proposal because the planned improvements would make “more than 500 acres of Elysian Park…more accessible than ever before.”[9] Under the terms of the proposal, $300,000 would go toward constructing a new lodge to replace the one torn down, plus new recreation facilities, basketball and tennis courts, an amphitheater, baseball diamond, picnic areas, and additional parking. Mayor Yorty called this “a great opportunity to turn Elysian Park into a far more desirable and usable recreation area,” rather than “a seldom used park that few of our citizens take advantage of.”[10]

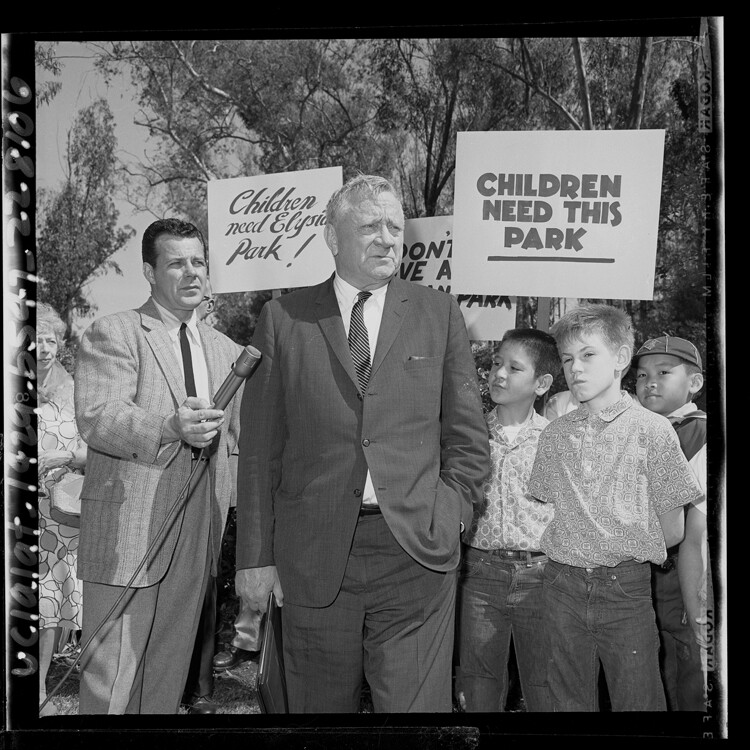

Enter Simons. She was incensed that the City Council dared to encroach once again on protected parkland and she quickly took action. Aided by her communist-organizer husband Glass, Simons launched the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park and crafted a well-organized and inventive 18-month grassroots campaign to block the Council’s plans. Simons’ lifelong commitment to social justice and her decades of journalism experience prepared her well for the battle. Once described as a “frail diminutive woman whose appearance belied her sharp mind and great fortitude,” Simons was known for being both “charming and demanding…when Grace spoke, everyone listened.”[11] She and the Committee built a cross-class, multiracial coalition of nearby residents and park users, labor leaders, elected officials, modernist architects, and conservation activists. The Committee’s multi-pronged crusade to save the park included legal strategies, public protests, and a powerful letter writing campaign.[12] They highlighted how no one could measure the “cost in sociological terms, in the loss of a needed recreational area, in the blighting of a residential neighborhood and in traffic congestion.”

The park's users, Simons said, “do not have chauffeur-driven cars to take them to the hills and the spas. Elysian Park is their playground.”

The Committee’s most effective strategy in halting the project was to frame the issue as a class battle. Public parks served as a back yard for those lacking one, especially Elysian Park because of its proximity to working-class neighborhoods like Echo Park, Boyle Heights, and Lincoln Heights.[13] As Simons put it, the park’s users were families who “do not own estates of their own, who cannot luxuriate in private swimming pools and who cannot afford to send their children to summer camps.” Where, she asked the Council, will youngsters go when the park is taken away from them? They “do not have chauffeur-driven cars to take them to the hills and the spas. Elysian Park is their playground.”[14] One nearby resident expressed dismay at the “total disregard … [for] citizens of the community…particularly the less affluent ones,” who need “aesthetic and spiritual refreshments – air, space, trees, grass, rolling hills.”[15] Another resident remarked that with the recent “population explosion,” the city needs “recreation centers … to keep our children…off the streets, [and] out of mischief.”[16] One incensed neighbor recalled how “we had the Chavez Ravine Ball Park shoved down our throats and our quiet streets became race tracks of traffic.”[17]

The battle for Elysian Park represented an opportunity for Angelenos to challenge the direction of urban planning and policy.

The sentiments evident in these letters show not only how deep the wounds from the Chavez Ravine controversy remained, but also that residents understood the extent to which a convention center in Elysian Park would adversely affect neighboring families, and create even greater park imbalances in the city. The letters also reiterated the belief that the convention center unfairly served the economic interests of elites to the detriment of the economically disadvantaged. As longtime residents of the Elysian Park neighborhood, Simons and other Committee members clearly understood what the park meant to the local community. They ultimately convinced the Council to reject the convention center plan, in part, because they were able to prove it would affect quality of life for the park’s neighbors and users. The Committee also succeeded because they operated within the context of renewed interest in conservation, park preservation, and urban beautification. The battle for Elysian Park represented an opportunity for Angelenos to challenge the direction of urban planning and policy, and to envision a different future for Los Angeles – one that valued open space and made for a more livable city. Simons set the standard for pursuing a conservation-minded vision that continues to inspire activists to this day.

Footnotes

[1] Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park, Collection No. 320, Box 6, Folder: Correspondence, Special Collections, USC Library, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. (Hereafter CCSEP Papers) “Elysian Park: What You Can Lose.“ The Avenue of the Palms is part of the Chavez Ravine Arboretum in Elysian Park, declared as City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 48 on 26 April 1967. The monument covers the area north of Scott Avenue to the intersection of Stadium Way and Elysian Park Drive.

[2] Elysian Park: New Strategies for the Preservation of Historic Open Space Resources (Los Angeles: UCLA Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, June 1990), VI–3; “Elysian Park: History and Current Issues,“ May 1990. Elysian park was initially 550 acres, had grown to 600 by 1937, and is now 575 acres, although continued threats jeopardize its acreage. The park is approximately 1.2 miles northwest of downtown. Part of a land grant in 1781 from the King of Spain to the pueblo of Los Angeles, Elysian Park is now the only remaining undeveloped parcel of the original land grant. The park’s acreage was one of three public land holdings set aside for public use in the city’s original Spanish land grants. The other two are the Plaza and Pershing Square. All three were placed under the jurisdiction of a Department of Parks established with the city’s first Freeholder Charter, adopted in 1889. See Sonenshein, Raphael J., Los Angeles: Structure of a City Government (Los Angeles: League of Women Voters of Los Angeles, 2006), 87–88.

[3] Elysian Park: New Strategies, II–16; Sonenshein, Los Angeles: Structure of a City Government, 87–88.

[4] Elysian Park: New Strategies; Elysian Park Master Plan, 1971; Withers & Sandgren, Ltd., Elysian Park Master Plan (City of Los Angeles, June 2006), http://www2.cityofla.org/RAP/dos/parks/elysianPK/elysianMasterplan.htm.

[5] Elysian Park: New Strategies, VI–5, VI–9 – VI–10; “Oil Lease Victory,“ CCSEP Newsletter no. Supplemental (January 23, 1966): 1; Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park, “Press Release: Road Through Elysian Park Opposed; New Route Mapped“ (CCSEP, May 19, 1966), Box 6, F: Press Coverage, CCSEP Papers; Simons, “Another ‘Land Grab‘ Focuses on One of L.A.’s Parks“ ; Phyl Diri, “Where the Brake Fern and Willow Find a Home,“ California History 62, no. 3, Magazine of the California Historical Society (Fall 1983): 168.

[6] Michael Eberts, “Recreation and Parks,“ in The Development of Los Angeles City Government (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City Historical Society, 2007), 607–608.

[7] The use of federal slum clearance policy and eminent domain to demolish a primarily working-class Latino community in Chavez Ravine during the 1950s created a lengthy and well-publicized controversy. The Ravine’s clearance for a public housing project—and the project’s subsequent cancellation—opened the way for the Stadium’s construction. For more on Chavez Ravine, see: Tom Sitton, Los Angeles Transformed: Fletcher Bowron’s Urban Reform Revival, 1938-1953 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 157–160, 165–169; Don Parson, Making a Better World: Public Housing, the Red Scare, and the Direction of Modern Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 110–117, 126–135, 145–147; Don Parson, “This Modern Marvel: Bunker Hill, Chavez Ravine, and the Politics of Modernism in Los Angeles,“ Southern California Quarterly 75, no. 3–4 (1993): 333–350; Eric Avila, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 207–208. On the stadium’s adverse effects on Elysian Park, see: Elysian Park: New Strategies, VI–4 – VI–5.

[8] Elysian Park was initially recommended as a potential site in December 1964 when California Governor Jerry Brown’s Committee to study potential locations for the 1968-1969 World’s Fair put forth Elysian Park as the leading location. The L.A. Convention Bureau, Inc. and the executive committee of the L.A. Chamber of Commerce supported the idea, but not all members of these organizations agreed it was a good choice. One Bureau director specifically objected because it would take away needed recreation space. See Paul Beck, “World’s Fair Site Urged in Elysian Park; Report to Brown Cites ‘Desirability, Feasibility‘ of Plan,“ Los Angeles Times, December 24, 1964; Paul Beck, “Convention Center Site in Elysian Park Backed; Bureau, Over Objections of Some of Its Members, Supports $10 Million Plan,“ Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1964.

[9] Department of Recreation and Parks, City of Los Angeles, “Statement on Proposed Municipal Auditorium in Elysian Park,“ April 26, 1966, Marvin Braude Papers, Box D-434, F: Elysian Park Correspondence, 1955-66, Los Angeles City Archives.

[10] “Press Release“ (Office of Mayor Sam Yorty, March 2, 1966), Marvin Braude Papers, Box D-434, F: Elysian Park Correspondence, 1955-66, Los Angeles City Archives; Paul Beck, “Elysian Park Plan Proposed by Yorty; Development Contingent on Exhibit Center,“ Los Angeles Times, March 3, 1966.

[11] Quotation comes from June 8, 1992, Cultural Affairs Commission bio of Frank and Grace, Box 7, Folder EP Collection, Peter Shire Memorial to Ges & Frank Glass, CCSEP Papers.

[12] Between the founding of CCSEP in February and the Council vote in March, Simons and CCSEP had enough time to begin building a coalition against the proposal and gather supporters to attend the March meeting in force to voice their opposition.

[13] “Elysian Park: History and Current Issues,“ circa 1982 or so, Box 6, F: Press Coverage, Mostly L.A. Times, CCSEP Papers.

[14] Grace E. Simons, “Elysian Park Must Be Saved for the People,“ early 1965, Box 7, F: Speeches, 1965, CCSEP Papers. Diri notes the increasing attacks on Elysian Park coincided with the abandonment of its surrounding neighborhoods by high society and the influx of poorer residents. See Diri, “Where the Brake Fern,“ 168.

[15] Ann Fink, “Reader Inveighs Against Proposed Elysian Park Convention Center,“ Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1965.

[16] Anna L. Halfries to L.E. Timberlake, February 12, 1965, Council File 122183, Los Angeles City Archives.

[17] Frank A. Amis to City Council, n.d., Council File 122183, Los Angeles City Archives. Amis believed ninety percent of the neighbors felt the same way.