California’s Atlantis: The Lost Superisland of Santarosae

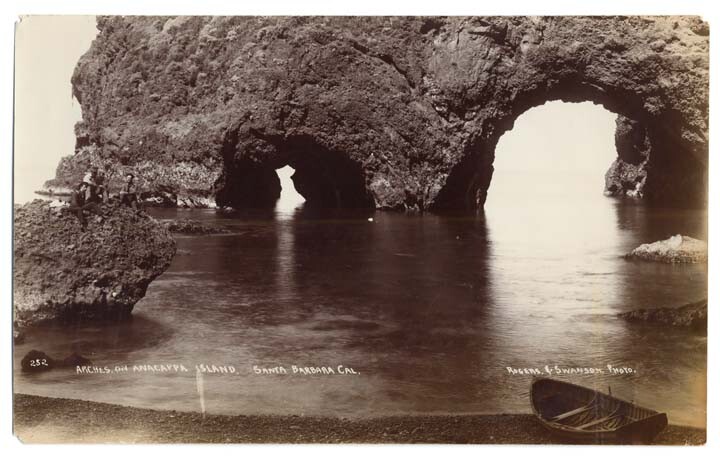

The premiere episode of SoCal Wanderer, KCET's new travel series, follows host Rosey Alvero as she takes a ferry from Ventura to Anacapa Island and learns about the fascinating history and ecology of Channel Islands National Park. Watch the premiere, "Anacapa to Ojai" online now.

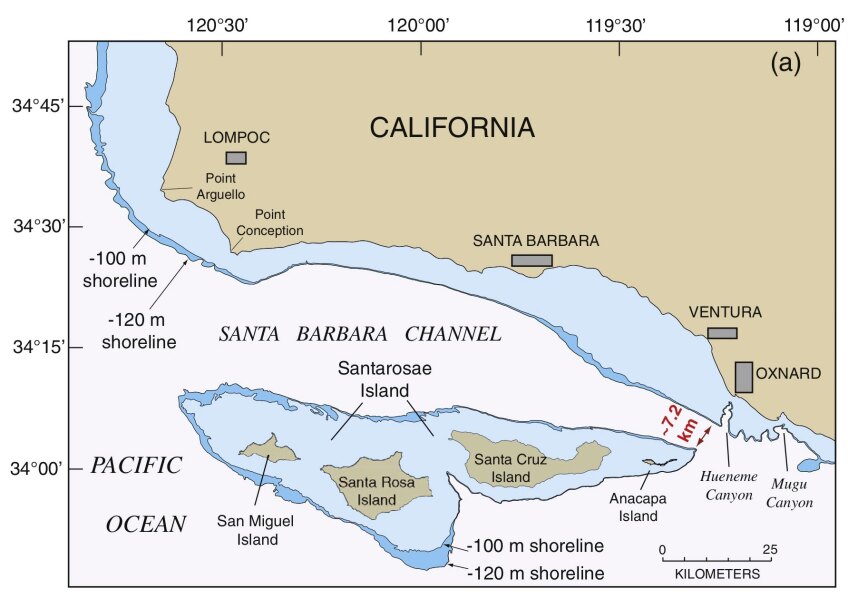

A superisland lies submerged beneath California’s cold Pacific waters. Twenty thousand years ago — a mere blink of an eye in geologic time — Santarosae Island, measuring 74 miles long and 829 square miles in size, lay very much above the water just south of the Santa Barbara coast.

Teeming with wildlife, pounded by surf, clothed in oak and pine and grass, this landmass would have seemed as permanent as the sky itself. And then the world started to change.

The cooler Pleistocene climate gave way to the warmer Holocene. Oceans heated and swelled. Sea levels rose even higher as continental ice sheets melted, unleashing prodigious quantities of water. Waves began to lap at continental shelves around the world, including the lowlands between Santarosae’s peaks, until the highlands were all that protruded from the sea. We know these superisland remnants today as the northern Channel Islands: San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz and Anacapa.

Tiny Anacapa was the first to separate, some 10,300 to 10,900 years ago, as rising waters slowly engulfed the narrow isthmus connecting it to the rest of Santarosae. This act of island dismemberment did not go unwitnessed. Humans already lived here, having arrived at least 12,710 to 13,010 years ago, and perhaps much earlier. They likely came by boat, following the food-rich “kelp highway” of underwater seaweed forests that stretched from northern Japan and Kamchatka, along Beringia’s southern shore, down the Pacific Northwest, and all the way to Baja California. Like many of the virgin lands they encountered, Santarosae Island would have seemed to offer its discoverers unlimited nourishment. From its shores they fished, hunted seals and sea lions and gathered seaweed and shellfish. On its extensive wetlands, fed by streams issuing from the island’s mountains, they hunted waterfowl. In its highlands, they harvested acorns. Even as the seas rose, drowning three-quarters of their productive homeland, splitting off Santa Cruz Island 9,400 to 9,700 years ago, then dividing Santa Rosa from San Miguel Island some 300 years later, these island-dwellers adapted, survived, and thrived.

The same cannot be said for Santarosae’s elephant, the pygmy mammoth. Standing “only” five and a half feet tall at the shoulders and weighing “a mere” 1,700 pounds, Mammuthus exilis was essentially a miniature version of the titanic mainland ancestor, the Columbian mammoth (M. columbi), that colonized Santarosae at some indeterminate point in the past.

How did these massive beasts cross the watery gap between island and mainland? The answer lies in a behavior observed in the world’s two extant elephant species: swimming. Contrary to our expectations, elephants are excellent swimmers, capable of crossing at least 30 miles of open water as fast as a human walks. And with so much of the continental shelf exposed in Pleistocene times, the channel that today is eleven miles wide then spanned, at its narrowest point, only four and a half.

At least once in the superisland’s prehistory, paleontologists now believe, a group of intrepid Columbian mammoths on the mainland must have deliberately swum across the Santa Barbara Channel, first bathing themselves in the surf where Santarosae’s peaks loomed on the horizon, then catching the whiff of island vegetation on the prevailing westerlies, and then deciding — boldly — to leave solid ground behind. Once across the channel, they would have lumbered ashore, shaken off the briny seawater, and made themselves a new home. Free of such fearsome mainland predators as the saber-toothed tiger, these gigantic mammals became smaller with each generation, evolving into a dwarf species that, despite its diminished size, ruled the island for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years.

And then, some 13,000 years ago, they disappeared.

Whether humans hunted the pygmy mammoth to extinction — or at least compounded the existing stresses of climate change and habitat loss — is still an open question. It’s notable that the radiocarbon date ranges of the youngest pygmy mammoth remains and the oldest human remains on the Channel Islands overlap by 200 years. Scientists also suspect that, some 2,270 to 2,240 years ago, the people of the Channel Islands drove another species extinct: Law’s diving goose, a flightless bird they had hunted for at least 8,000 years.

These people — likely ancestors of those known in historical times as Michumash or Island Chumash — didn't simply subtract. They also added new species to the islands. Some may have crossed the channel in canoes with the deliberate help of the Chumash paddlers: pet dogs, for example, or, some 6,200 to 6,400 years ago, the ancestor of the island fox (Urocyon littoralis). Others probably crossed without ever making the canoes’ passenger manifests: the gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer pumilis), the spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis amphiala), and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). And yet, when these stowaways scampered ashore, they quickly found their ecological niches. Despite their mainland origins, animals like the deer mouse soon made the islands their adopted home.

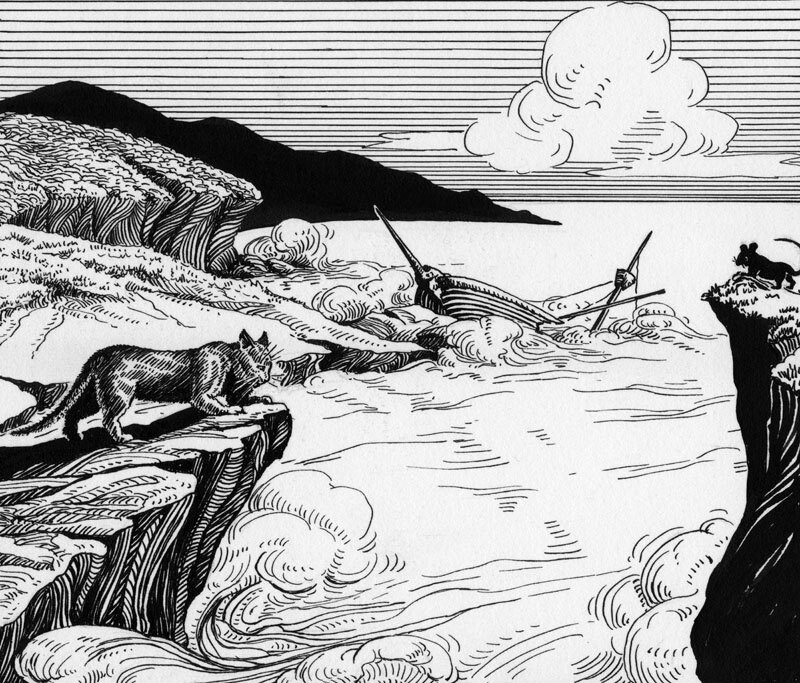

Thousands of years later, another stealthy rodent scurried ashore from the cargo hold of a 225-foot sidewheel steamer and, like the deer mouse before it, made Anacapa its own. An hour before midnight on the evening of December 2, 1853, the SS Winfield Scott, making one of its regular coastal voyages between Gold Rush-era San Francisco and Panama and laden with $801,871 in gold and several tons of mail, crashed into Anacapa Island at full speed. Miraculously, all of the ship’s 300-plus human passengers survived — as did many of the black rats (Rattus rattus) fleeing its drowned cargo holds. Together, the passengers and rats found safety on Anacapa’s rocky shore. Within a week the castaway humans were rescued; the castaway rats, meanwhile, remained on the island, where they feasted on bird eggs and deer mice and multiplied.

The black rat’s arrival was only one in a long string of dramatic changes the Channel Islands endured as European empires (the Spanish and Russian) and the political descendants of European empires (Mexico and the United States) supplanted the Chumash as masters of the Santa Barbara Channel. American ranchers let loose their livestock, and soon the hooves of their cattle eroded the landscape. Their sheep and pigs became feral, disrupting food chains, as did deer and elk, originally introduced as game for tourist hunters. Even earlier, Russian and Aleut hunting parties helped decimate the island Chumash’s population, taking otter pelts and leaving behind death and disease. By the 1820s, the Spanish and Mexican authorities had forcibly removed the surviving Chumash to missions on the mainland, leaving Santarosae and its remnants — for the the first time in at least 12,000 years — uninhabited.

A chain of uninhabited islands just off the coast of California, all boasting rare endemic animal species as well as sea-salt scenery, might seem an obvious location for a national park. And yet Channel Islands National Park is relatively young, born in 1980. (A much smaller Channel Islands National Monument, dating from 1938, protected only tiny Anacapa and remote Santa Barbara Island.) In its 38 years as steward of San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa islands, the National Park Service, guided by its stated mission to preserve natural and cultural resources, has remarkably departed from an earlier tendency to simply pause landscape change. On the Channel Islands, it has actually tried to reverse it, hunting the 5,036 feral pigs of Santa Cruz Island to extinction, eliminating deer and elk from Santa Rosa Island, and showering (by helicopter!) Anacapa Island with rat poison pellets.

It takes only a little imagination to envision a range of hypothetical Park Service-sanctioned experiments in restoration ecology, from the merely unlikely (allowing the exiled Chumash to once again make their homes on the northern Channel Islands) to the outlandish (reengineering and reintroduction of the pygmy mammoth) to the obscene (a climate modification program that would return the Earth to Ice Age conditions, thus lowering sea levels and resurrecting Santarosae Island). In reality, Anacapa may never reunite with its sister islands, and certainly not within our lifespans. And yet, with the eradication of its invasive rats, the island’s rare birds and deer mice are thriving. Recent human history has been turned back, if not erased. Anacapa has come to resemble, just a bit, the ancient superisland of Santarosae.

Further Reading

Agenbroad, Larry D., John R. Johnson, Don Morris, and Thomas W. Stafford, Jr. “Mammoths and Humans as Late Pleistocene Contemporaries on Santa Rosa Island, Channel Islands National Park, California.” In Proceedings of the Sixth California Islands Symposium, Arcata, CA, December 1-3, 2003, 3–7. Arcata, CA: Institute for Wildlife Studies.

Braje, Todd J., Tom D. Dillehay, Jon M. Erlandson, Richard G. Klein, and Torben C. Rick. "Finding the First Americans." Science 358, no. 6363 (2017): 592-594.

Erlandson, Jon M. “Seascapes of Santarosae: Paleocoastal Seafaring on California’s Channel Islands,” In Marine Ventures: Archaeological Perspectives on Human-Sea Relations, edited by Bjerck, Hein Bjartmann, 325-35. Bristol, CT: Equinox, 2016.

Gamble, Lynn H., ed. First Coastal Californians. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015.

Lister, Adrian, and Paul Bahn. Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age. Rev. ed. New York: Chartwell Books, 2015.

Muhs, Daniel R., Kathleen R. Simmons, Lindsey T. Groes, John McGeehin, and R. Randall Schumann. "Late Quaternary Sea-level History and the Antiquity of Mammoths (Mammuthus exilis and Mammuthus columbi), Channel Islands National Park, California, USA." Quaternary Research 83, no. 3 (2015): 502-21.

Rick, Torben C., Jon M. Erlandson, René L. Vellanoweth, Todd J. Braje, Paul W. Collins, Daniel A. Guthrie, and Thomas W. Stafford, Jr. "Origins and Antiquity of the Island Fox (Urocyon littoralis) on California's Channel Islands." Quaternary Research 71, no. 2 (2009): 93-98.

Top Image: Inspiration Point at Anacapa Island, Channel Islands National Park | Courtesy of KCET