Broadsides Reveal L.A.’s Once-Booming Hispanic Vaudeville Scene

Downtown Los Angeles isn’t what it was a century ago, but the ghosts of its past still haunt the streets. Remnants of the city’s history remain in the weathered facades of many of its buildings. The Orpheum Theatre on Broadway Boulevard, for example, stands as a living testament to the city’s lively vaudeville scene, as it was once home to numerous variety shows from the early to mid-20th century. The Diamonds Theatre jewelry mart on 7th and Hill also hosted many vaudeville entertainers during the 1920s when it was known as the Pantages Theatre, its original location before the construction of its glitzy sibling in Hollywood.

“Between 1910 and 1926,” writes Stan Singer in his research article “Vaudeville in Los Angeles, 1910-1926: Theaters, Management, and the Orpheum,” “variety theater realized a meteoric and sustained rise as one of the entertainment attractions in Los Angeles. The popularity of vaudeville is indicated by a surge in the building of theaters over a short period of time.”

At one point, 20% of the 71 theaters in Los Angeles in the 1910s were designed specifically for vaudeville and small-time variety shows, according to Singer’s research. As the city grew and the entertainment industry changed, these theaters were either repurposed or demolished entirely. As such, much of L.A.’s vaudevillian past exists today only through the careful preservation work of scholars, academics and passionate fans of vaudeville and theater.

Researchers at the USC Digital Library, for example, have been working with the Workman & Temple Family Homestead Museum to digitize various artifacts from the museum’s collection. Of these items, the collection includes a pair of broadsides from a theater in Los Angeles that hosted vaudeville acts performed entirely in Spanish.

The broadsides are announcements for two shows at the Teatro Principal where local and international talent shared the stage to produce numerous comedies, plays and musical performances. The shows, scheduled on January 9th and January 10th, 1929, were performed towards the end of the what was once a renaissance in Los Angeles for vaudeville en español, when local troupes, as well as touring groups from Mexico, Spain, Cuba, Argentina, & others, regaled audiences in L.A. with their performances.

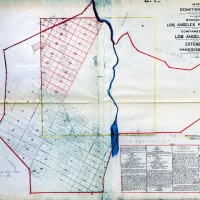

“Los Angeles was able to support five major Hispanic theatre houses with programs that changed daily,” writes Nicolás Kanellos in “A History of Hispanic Theatre in the United States: Origins to 1940.” “The theatres and their peak years were Teatro Hidalgo (1911-1934), Teatro México (1927-1933), Teatro Capitol (1924-1926), Teatro Zendejas (later Novel; 1919-1924) and Teatro Principal (1921-1929). Four other theatres…were also important, and at least fifteen others housed professional companies on a more irregular basis between 1915 and 1935.”

Click left and right to see some broadsides from the archives:

The Teatro Hidalgo has the distinct honor of being immortalized on film thanks to the work of the legendary filmmaker and actor Buster Keaton. In his film “Cops,” the large sign of the Hidalgo hangs prominently in the background as a mob of police officers chase after Keaton in the foreground of a scene in the final third of the film.

Unseen in the sequence is the Teatro Principal, which sat a few hundred feet to the north of the Hidalgo. Today, the 101 freeway cuts through what was once the Hidalgo while a parking lot for the La Plaza de Culturas y Arte resides in the space formerly held by the Principal.

Kanellos traces the first Spanish-language theater performance in California to 1789. It would be decades later, in the years after the Mexican-American War, that Hispanic theatre would begin to grow. Various theaters hosted Hispanic performers and plays in the mid-to-late 19th century in the city, including at the Grand Opera and the Teatro de la Merced, the latter known today as the Merced Theatre in the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument.

It was the opening of the Teatro México and the Teatro Principal in 1921 that initiated what Kanellos calls the “decade of the greatest Hispanic theatrical activity in the history of the United States,” thanks to a combination of local and foreign talent. One influential factor leading to this time was the growth of the film industry in Los Angeles.

“In fact, Los Angeles became a manpower pool for Hispanic theatre,” explains Kanellos. “Actors, directors, technicians and musicians from throughout the Southwest, New York, and the whole Spanish-speaking world were drawn here looking for employment. Naturally, Los Angeles became the center for the recruitment of talent in the formation of theatrical companies to perform either locally or on tour through the Southwest.”

One of the more high-profile artists in that regard is that of Victoria Fábregas, an actress whose company toured the Southwest and performed serious, contemporary works from Mexico City and Europe, thus keeping audiences entertained with the latest works from both continents. Fábregas also supported playwrights from Los Angeles by purchasing the rights to their works and integrating them into her company’s tours. A few members of her company also defected and remained in the Southwest where they launched their own vaudeville troupes and theatre companies. The vaudeville scene in Los Angeles, for example, benefitted from the defection of Agustín Molinari who created a familial legacy of vaudeville and theatre through his three children.

L.A.’s Hispanic vaudeville scene slowly fizzled out after 1929 until vaudeville itself became a relic of a bygone era. However, the spirit of those who led the city’s Hispanic vaudeville and theatre renaissance continues thanks to numerous artists, theaters and troupes throughout L.A.

Casa 0101 in Boyle Heights is a small 90-seat theatre and community arts space that has fostered performance arts for a Latinx audience since its founding in 2000. One of their most beloved works is a bilingual version of Disney’s “Aladdin” film, titled “Aladdin: dual language edition / edición de lenguaje dual.” On the other end of the spectrum are Culture Clash, a nationally-renowned performance group featuring Richard Montoya, Ric Salinas and Herbert Sigüenza, who have produced various works of social and political satire for comedies, stage plays, films, and more since 1984.

Writer/performer Rubén Martínez carries the torch passed on from his paternal grandparents, the acclaimed vaudeville performers Juan Martínez and Margarita del Río (aka “Martínez del Río”), who regaled audiences in some of the best theatres in the city. Years ago, Martínez produced “Variedades: Olvera Street,” a work that explores the history of Los Angeles and Olvera Street using vaudeville as a key influence.

This new generation of performers continue the work spearheaded by the trailblazers of the past in Los Angeles and their works form the next phase of the larger body of creative work that represent part of what Kanellos describes as the Hispanic tradition in the United States.

“The Hispanic tradition in the United States is not one that can be characterized exclusively by social dysfunction, poverty, crime and illiteracy, as the media would often have us believe,” says Kanellos. “Rather, if we focus on theatre, we can draw alternative characterizations: the ability to create art even under the most trying of circumstances, social and cultural cohesiveness and national pride in the face of racial and class pressures, cultural continuity and adaptability in a foreign land.”

The project to digitize selected materials from the Workman & Temple Family Homestead Museum has been made possible in part by a major grant to the USC Libraries and L.A. as Subject from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor.

Top Image: Broadside for Teatro Principal, Los Angeles, printed at Jalisco Print Shop, Boyle Heights, 1929 January 09. | University of Southern California Libraries, Workman and Temple Family Homestead Museum Collection, 1830-1930