Before Rosie the Riveter: L.A. Women and the First World War

During World War II, the image of Rosie the Riveter, the U.S. government’s attempt to promote women’s participation in war industry production, dominated the popular imagination. Afterwards she would serve a symbol for the burgeoning feminist movement that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. However, the opportunities that Rosie the Riveter encapsulated and the movement that followed didn’t begin with the Second World War; they were in many ways the descendants of earlier efforts by women during the First.

This year marks a century since the United States entered “The Great War,” and across the nation, exhibitions dedicated to the conflict are opening. For example, on April 4th, the Library of Congress debuted its exhibition “Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I.”. Many such pubic remembrances emphasize the critical role that such contributions played in fighting the war, but also in leading to the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted women the vote nationwide in 1919. Despite larger reservations about the war, moderate suffragists (women advocating for the right to vote) as represented by the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) committed to the war effort through volunteerism, which proved critical in mobilizing the home front.

Lynn Dumenil, a histoprian at Occidental College and author of the recent book The Second Line of Defense American Women and World War I, knows a great deal about women, World War I, and Los Angeles. In a 2011 article, Dumenil argued that World War I “was a watershed [moment] in the history of Los Angeles.”[1] Wartime mobilization in Los Angeles deeply affected women, and women in turn deeply impacted mobilization.

Los Angeles women provided crucial labor in making the 19th Amendment a reality. At the same time, they laid the foundation for the Rosie the Riveter feminism that followed decades later.

Even before the war broke out in Europe, Angeleno women played a critical role in national politics. Unlike in most other states, in California women had gained the right to vote in 1911. The state proved decisive in reelecting Woodrow Wilson in 1916, and some, like newspaper editor Desha Breckinridge, credited the vote of women in California and the West with delivering Wilson’s victory.[2] By 1917, only 12 states, including California, gave women the right to vote. The war provided the opportunity, some women argued, to demonstrate exactly why they deserved the franchise. Los Angeles women provided crucial labor in making the 19th Amendment a reality. At the same time, they laid the foundation for the Rosie the Riveter feminism that followed decades later.

L.A. Women

In the years leading up to America’s entrance into the war, most suffragists opposed intervention. Jane Addams and Carrie Chapman Catt provide just two prominent examples. Once the U.S. entered the war, however, moderate suffragists like Addams and Catt decided the best way to promote women’s rights and suffrage would be through contributions to the war effort.

In Los Angeles, one detects this tension persisting even after U.S. intervention in April 1917. The Southern California division of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a women’s organization that advocated for alcohol prohibition but also supported suffrage, approved a September 1917 resolution opposing the war, criticizing military training, and calling for a negotiated peace settlement. In a recent interview, Chapman University historian and World War I expert Jennifer Keene told me that such divisions were “indicative of nationwide sentiment.” Keene noted that the government adopted a “heavy handed approach” to convince the public of the war’s efficacy. “So the idea that women’s groups were divided, I find that healthy and normal.”[3] Despite the local WCTU’s statement of militancy, the organization soon fell in line with war efforts, working with the Women’s Committee of the National Council of Defense (WCCND) in coordinating local mobilization efforts.[4]

How to pursue suffrage proved a challenge to women’s rights advocates, though Los Angeles female residents had a bit more leeway having already gained the franchise. “[Southern California] suffrage groups had to consider what their antiwar positions might mean in regard to the larger movement,” Keene said. “In California they didn’t have to factor that into whether or not they would protest or support the war so in that sense it liberated them.”[5]

Still, the need for a national constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to vote remained a central issue for the city’s clubwomen. An influential women’s group, the Friday’s Morning Club, drew directly on this connection when it adopted a resolution arguing that giving women the right to vote nationally was a necessary war measure “by which all American womanhood will be encouraged to co-operate in a war service as enfranchised responsible citizens.”[6]

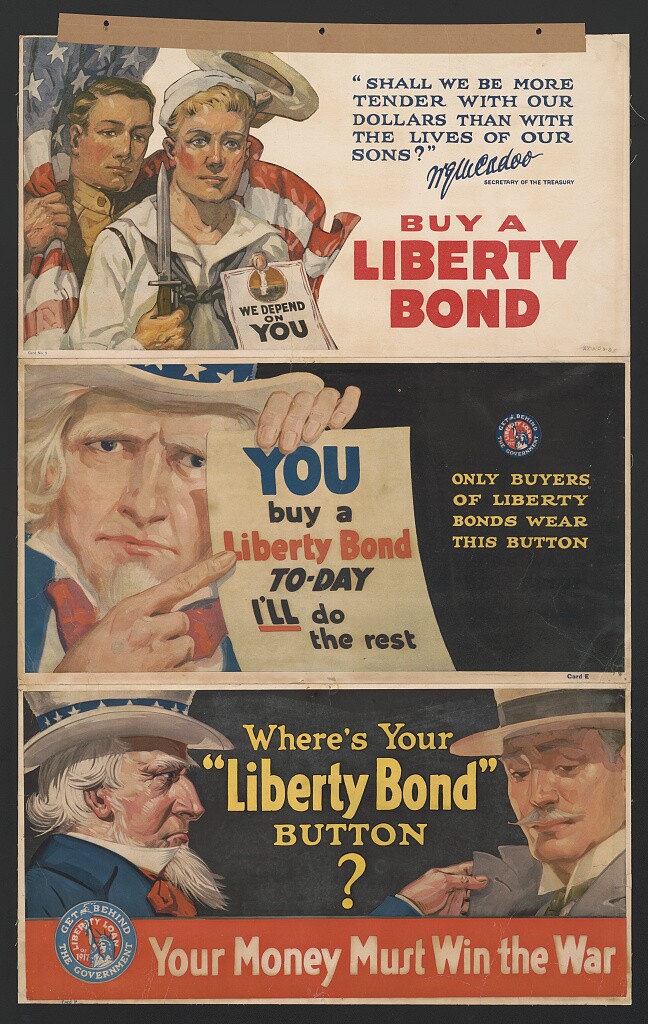

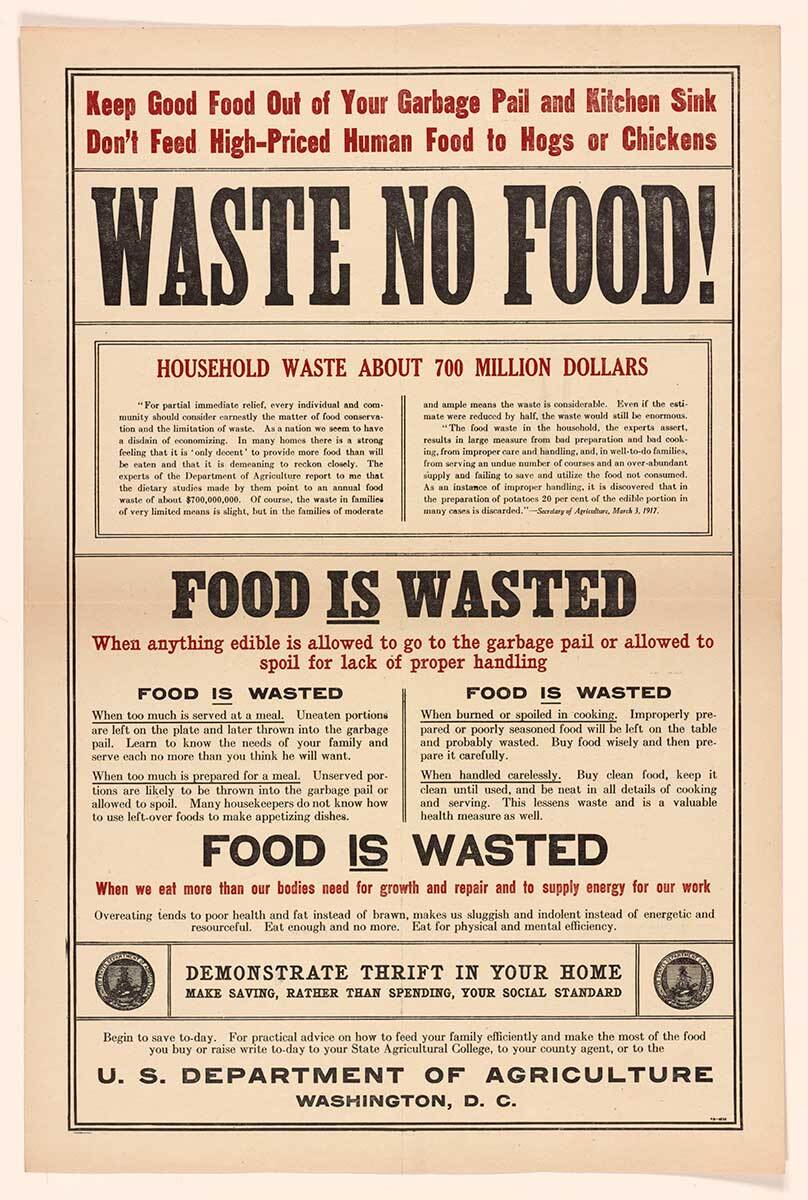

Clubwomen, mostly middle-class and upper-class white women with memberships in the WCTU and other organizations like the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), proved critical in mobilizing the war effort at home including the promotion of Liberty Loans to fund the war or to encourage voluntary food conservation. In regard to the latter, L.A. led the nation’s cities in obtaining Pledge Card Enrollments in which families promised to reduce their consumption of food stocks like meat or wheat. Some 15,000 women secured 215,000 pledges by local households to work toward food conservation during the war.[7]

Being tied into the national network of women’s clubs, Los Angeles women were particularly well positioned. The California branch of the Women’s Committee of the National Council of Defense was especially active; it consisted of 29,000 members.[8]

The Los Angeles committee of the WCCND engaged in “an elaborate door to door canvassing, a procedure used elsewhere in the state,” writes Dumenil. Referred to as its Women’s War Service Army, it enabled the city’s clubwomen to conduct a census that aggregated information about residents including “names, addresses, military status and citizenship of ‘every man, women and child … so that information could be … quickly utilized for some specific services, such as food conservation notice, or relief work …’”[9]

Though a diverse city in 1917, Los Angeles embodied the kind of racial hierarchy that existed across urban America at the time. For example, J.T. Anderson, the local chairman of the WCCND, effectively organized some 350 women’s groups in the city, which, judging from its elected board members, achieved some level of inclusivity. Representatives hailed from the Catholic Women of Los Angeles, the Jewish Women of Los Angeles and Labor Organizations, however, no women of color appear to have been board members.[10] Mexican-American and Japanese-American women contributed, but did so at the rank and file level, as they were denied access to higher, decision-making roles.[11] As Dumenil and other historians have noted, white clubwomen invoked their wartime service in the language of citizenship and the right to vote, but “implicitly defined that citizenship as white and privileged.”[12]

Black women also certainly contributed to war efforts. Prior to U.S. involvement, Los Angeles was the “hub of [black] club activity” and the Sojourner Truth Industrial Club (STIC) had the oldest pedigree and largest membership. During the war, the STIC organized local African-American clubwomen, but white organizations largely ignored them. “Negro Women Councils” formed by African-American women in Pasadena and San Diego worked with the local WCCNDs supporting the war but also remained attuned to racial issues, such as when they protested D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of the Nation,” a film that portrayed the Klu Klux Klan positively and promoted noxious racist stereotypes of African-Americans.[13]

Red Cross

Of course, any discussion of women’s service during wartime must mention one of the most iconic organizations of the 20th century: the Red Cross. Here, too, L.A. women played a critical role. Both men and women volunteered and worked for the Red Cross; nationally, its leadership positions were dominated by men, but in Los Angeles women made up half its board of directors. Images of nurses on the war front often dominate the public imagination, but many more women sewed or knitted clothes for soldiers, made bandages, assembled care packages and “comfort bags”, or served coffee, donuts, and other refreshments at railway stations across the U.S. Los Angeles’ Santa Fe Station served as a hub of this kind of activity during the war.[14]

Worried about the disruption to families caused by conscription, the L.A. branch of the Red Cross organized the Home Service responsibility program in fall of 1917. Through it, the Red Cross provided “financial aid, medical care, and legal advice” dedicated to ensuring that “no enlisted man’s family shall suffer for any essential thing that it is within [the Red Cross’s] power to give.”

Female Red Cross volunteers in Los Angeles signed up individually but also through and with their clubs. Though the Red Cross worked well with white middle and upper class clubwomen, it also successfully marshaled, if on admittedly unequal terms, the labor of Jewish, Japanese, Mexican, and African American women in Los Angeles.

Forming their own auxiliaries, Jewish and Japanese women contributed to the local war effort. According to the Los Angeles County war history committee, most Japanese Angelenos joined the Red Cross and provided the “most consistent war work” and described their contributions as “praiseworthy.” Mexican-American women worked at the local Catholic settlement house, Brownson House.

African-Americans contributed to efforts through the Harriet Tubman Auxiliary in Los Angeles and the Phyllis Wheatley branch of the Red Cross in nearby Santa Monica. Due to the segregated nature of the military and the large numbers of black service personnel serving in the war (roughly 400,000 African-American men traveled overseas for the army), these organizations viewed their work as including support for their enlisted male counterparts. They held banquets to send off local troops in good spirits. Unfortunately, the Red Cross also suffered from its own racial blind spots. Each group worked individually with little to no contact with each other, and certainly not with their Anglo peers. [15]

Then again, an epic 1918 Red Cross parade through Los Angeles gave these women, white and non-white alike, a public presence that even a decade earlier had been denied to them. “Never in Los Angeles had there been a parade where its womanhood took such a conspicuous part,” the Los Angeles Times reported. Some 10,000 marchers, most of them women and including Mexican and black participants, walked in the seven-mile parade to celebrate women’s war service.

Public demonstrations like the 1918 march drew publicity and highlighted the critical contributions of women to the war. It also provided justification for the demands of suffragists. Historians like Keene and Woodrow Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper Jr. credit these efforts with forcing the president to support suffrage. The 19th Amendment passed Congress in 1919 and was ratified the following year.

Obviously, limits remained. During World War I, most organizations and even the WCCND denied women real policy influence. Women of color continued to suffer discrimination as many white clubwomen ignored or discounted them entirely. For women generally, suffrage hardly meant equality. For example, one million women found better paying work in industry and elsewhere during the war, but labor union hostility curtailed these gains and the return of soldiers from Europe revealed the temporary nature of such opportunities. Yet, it also accelerated the slow march toward equality.

As symbolized by Rosie the Riveter and evidenced by the feminist movement that followed, women in World War II built on the accomplishments of their World War I counterparts. Given the increasing industrialization in Los Angeles during the interwar years, L.A women played an even larger role in the Second World War. But without the clubwomen of the First, a century ago, the story would have been very different.

Notes

[1] Lynn Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Vol. 10 No. 2 (April 2011): 218.

[2] Desha Breckinridge to Mary Curry, November 10, 1916, Breckinridge Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; John Milton Cooper Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography, (New York, Random House: 2009), 356.

[3] Jennifer Keene, interview with author, March 27, 2017.

[4] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 233.

[5] Keene, interview with author, March 27, 2017

[6] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 223.

[7] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 243.

[8] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 222.

[9] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 220.

[10] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 220.

[11] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 221.

[12] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 221.

[13] Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, “’Your Life Is Really Just Not Your Own’: African American Women in Twentieth Century California” in Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California, Eds. Lawrence B. De Graff, Kevin Mulroy, Quintard Taylor (Los Angeles: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 1984), 216-217.

[14] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 235-236.

[15] Dumenil, “Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I – Era Los Angeles”, 236-237.