A Guide to Gay Los Angeles, 1965

Written for the Hungry

“He who is everywhere is nowhere.” – Seneca the Younger

Before there was Grindr, there was The Address Book.

This guidebook, like all guidebooks, was written for the hungry. Its slogan, “See America. Find a friend,” hinted at the exact nature of its readers’ appetites while skirting the particularities.

Friends of Dorothy, and Sappho, turned to The Address Book, which debuted in 1965, to map their pursuits. The baedeker advertised via mail order, in-the-know bars sold it, and the initiated flung their bedraggled copies into the hands of the desperate. Butterflies must’ve fluttered in many a hopeful reader’s stomach as they skimmed the guidebook’s list of restaurants, bars, and nightclubs: these addresses offered potential antidotes to sadness.

The guidebook’s author, Bob Damron, gave gay readers hope by fleshing out worlds that would’ve otherwise remained unknowable. His list confirmed that a gay America existed and that within this quasi-nation, many smaller gay Americas proliferated. Each one was bound by unique affinities whose siren songs went muffled. With tact, Damron amplified these calls. His guidebook told where to find doorways flowing towards danger and joyful possibility. It pinpointed thresholds leading to family, community, sex, and love.

King of the Bars

Like many American revolutionaries, Damron worked in the alcohol industry. Men who knew him painted the barkeep as a pioneer who embodied both stud and sissy.

Hal Call partnered with Damron to publish The Address Book’s first few editions. Call, long-time president of the Mattachine Society, characterized Damron as LGBT royalty. Bookstore owner Ron Ernst said Damron belonged to a macho breed of homo entrepreneur that refused to kowtow to civic authorities, especially cops attempting to extort “gayola.” Drag performer Larry Buttwinick described Damron as energetic, ambitious, and, above all, a hell of a good bridge player.

During the 1950s, Damron ran a Hollywood bar, Melrose Avenue’s the Red Raven. Its moniker followed the homosexual place-naming practice of pairing a color with an animal. San Francisco’s now-defunct White Swallow bar best, and most tastefully, exemplifies this camp tradition.

At the Red Raven, men wearing pinky rings and loafers swallowed rum and cola. Eyes sought eyes. The scent of weenies grilling around the corner, at Pink’s hot dog stand, wafted beneath nostrils. Good-looking bait disguised in pinky rings and loafers leaned against Damron’s counter, gazing at clientele, waiting for somebody to make his move.

Plainclothes cops watched the plants. Their fingers stroked hidden black jacks. They waited to trounce.

Police raids of the Red Raven are well documented. Anecdotes suggest that the LAPD sometimes used down-on-their-luck actors or especially good-looking cops to entrap men, and among those arrested during one Red Raven snare was a retired callboy, Bill Rau, and an editor of a chemical trade journal, Richard Mitch. The event galvanized the lovers and the couple went on to transform the small activist newsletter they ran into The Advocate, the nation’s leading LGBT publication.

Although early and mid-20th century descriptions typify Los Angeles as teeming with gays (poet Hart Crane gushed that the number of “faggots” he saw cruising Pershing Square as “legion”), locating a place like the Red Raven required more than observation. Seekers depended on word-of-mouth references. Lists unintended for commercial consumption also supplied interested parties with addresses. In 1955, before partnering with Damron to create their official guide, Call produced such a document.

“I made up a mimeographed list,” he said, as quoted in James T. Sears’ “Behind the Mask of the Mattachine.” “It had thirty-five gay bars. We had people sign for it because we didn’t want it to fall into the hands of police.” The list was so valuable, and potentially incriminating, that Call numbered each copy to track its circulation.

About Damron’s method of collecting entries, Call said, “[Bob got] the opportunity to travel the United States and to be welcomed in all of the gay bars. He would go to the main cities and find out from those gay bars where there were homosexual bars elsewhere in the state. He was treated like a king.” The image of Damron as a tall, strapping figure Lewis and Clarking his way from beach to hinterland allies the guidebook’s shaky origin story with American frontier lore.

And Now, It's a Chipotle

Despite The Address Book’s reputation as the gold standard among homosexual baedekers, it’s important to note that as a pre-Stonewall (1969) document it conceived of gay space in ways that would be dismissed now.

Danny Jauregui, an art professor at Whittier College, says Damron didn’t visit and vet every site he listed. In fact, “The Address Book” was more of a gossipy collaboration “created via people sharing their trysts with [Damron]. If a guy got lucky at a restaurant, it got included.” Jauregui waxes poetic about The Address Book, calling it “sexual memory…told by spaces.”

Gentrification pushed Jauregui to discover The Address Book. It became his muse.

While living with his boyfriend in Silverlake, Jauregui had noticed his neighborhood changing. What had seemed a gay place when they moved there was becoming less so. This straight shift coincided with the Proposition 8 campaign to ban same-sex marriage in California. The campaign leased a Silver Lake storefront Jauregui regularly drove past, and witnessing his neighborhood’s transformation gave Jauregui the urge to research its history. In doing so, he discovered that the Prop. 8 offices once housed a gay bathhouse. Jauregui describes this historical discovery as “poignant.” The discovery prompted him to begin painting bathhouses in ruins and to continue his research.

Curiosity led him to the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, where an archivist showed him well-worn copies of The Address Book. Jauregui grew fascinated and when Whittier College gave him a grant for a digital project, he knew he had to use the money to revivify The Address Book’s gay Los Angeles.

“I wanted to visualize the rise and fall of these spaces,” he says. “I wanted to see it on a map. I started inputting every single address one by one into the software. I’ve only gotten to 1983.”

Jauregui’s digitally animated map lives and glows here.

Andy Rutkowski, a geospatial librarian at UCLA, is helming another Damron-inspired mapping project. He has collaborated on it with Cynthia Wang, a professor of communications at Cal State LA. She is behind the geolocational project Global Traqs. attempts to map LGTBQ histories across space and time from an international perspective.

Wang speaks to the drama of invisibility, stating, “I’m Asian. I can’t walk down the street and pass as white. That doesn’t happen in the LGBT community. There are gender exceptions, but historically, queer people have passed [as straight.]” While Global Traqs seeks to decrease queer isolation, Wang also concedes that collecting queer stories is “just sort of cool.” She adds, “No one’s known about [these communities]. They were almost like secret societies and now, [through geospatial digitization], you can see this place that used to be a really important bathhouse and now, it's a Chipotle.”

The Nation’s Largest City in Area

Pre-Stonewall editions of The Address Book lend themselves more easily to digital mapping projects than later editions. They’re skinnier, contain fewer addresses, and could easily fit into a wallet, tucked between a condom and a prayer card. Their pocket-size whispers discretion. Their covers look stark, nearly colorless, and come off as suspiciously unpretentious. Their lists are printed on pages of what Call referred to as “Bible paper.”

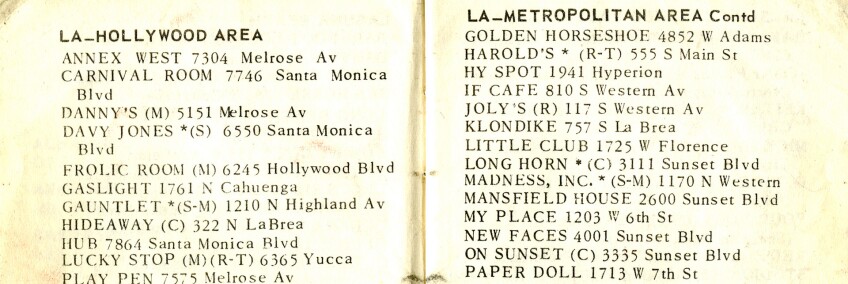

Los Angeles reigns as a gay attraction in these midcentury editions. The city’s 1968 entry begins “L.A. is the nation’s largest city in area.” It proceeds to divide the metropolis into four zones: Hollywood, the Metropolitan area, the San Fernando Valley, and the West and Southwest. To underscore sprawl, bedroom communities, from Dana Point to San Bernardino, receive mention. Asterisks dot the most popular spots and mark legends like Western Avenue’s If Café, Lankershim Boulevard’s Joani Presents, and Vermont’s Open Door. The letter G, for “Girls, but rarely exclusively,” accompanies these three entries.

Other abbreviations, ranging from C for Coffee to SM for Some Motorcycle, mark the 1968 list. These letters belong to a code whose explanation appears at the front of each guidebook. The rich alphabet stew of abbreviations printed alongside LA’s listings shows that the city had a robust and heterogeneous homosexual nightlife. The letters conjure sights, odors, and sounds both glamorous and gross. Lusty readers could envision steam rising from Santa Monica Boulevard’s Apollo Health Baths. They could imagine inhaling a cocktail of armpit, tobacco, and freshly polished leather at Highland Avenue’s Gauntlet (SM). They could almost hear nocturnal waitresses splashing greasy java into mugs at Ventura Boulevard’s Hayloft (C).

As the gay movement strengthened, Damron’s abbreviations evolved. The Address Book’s codes diversified and lost certain subtleties.

Post-Stonewall codes, like BA, defined as “Bare-Ass (usually nude beach),” underscored a new spirit of openness. Early codes seemed preoccupied with safety and Damron’s explanations made hinky use of polari, gay slang. Manipulating polari threw those unfamiliar with the dialect off the gay scent, and Damron’s choice to define SM as “Some Motorcycle” instead of sadomasochism, illustrates his style of obfuscation. S’s “Shows, often impersonators and record pantomime acts” more specifically denoted drag revues. RT’s “Raunchy Types, often commercial” was a nod at rough trade, working class or thuggish guys down for gay sex, especially if paid.

As Damron was compiling his 1969 list, very rough trade took part in one of Hollywood’s bloodiest outings. Brothers Paul and Tom Ferguson beat silent film star Ramon Novarro not with a lead dildo, as Kenneth Anger wrote in “Hollywood Babylon,” but with his silver-tipped cane. He gasped and gurgled in his Spanish style home on Laurel Canyon Boulevard. The ensuing scandal exposed the Mexican-born actor, known for playing Latin lover roles, in two ignominious ways. First, the hustlers left him in his bedroom, nude, broken-nosed and choking to death on his own blood. Second, during the murder trial, every detail of Novarro’s sex life spilled into the courtroom and public record.

Less than two miles from this Studio City crime scene stood Beverly Shaw’s Club Laurel, one of the first lesbian nightclubs to appear in the San Fernando Valley. Its signage featured a winking Shaw wearing a strawberry blonde pompadour and a bow tie. The Address Book listed its location as 12319 Ventura Boulevard (G). Club Laurel vanished from Studio City the same year Novarro did.

The Beautiful Gesture of a Red Line

Jauregui is discussing his fascination with anonymous notations jotted in pre-Stonewall copies of The Address Book.

“There are certain addresses crossed out. Someone has written in new names and locations,” he explains. “The beautiful gesture of a red line crossing out an address speaks to erasure of space, a rapid turnover.” Jauregui finds so much poetry in these red lines that he replicates them in “Disguised Ruins,” his “multimodal project consisting of a geospatial animation and accompanying video that maps and animates the opening and closing of every queer space that appears in the Los Angeles section of…The Address Book.”

The treatment of The Address Book as geographic palimpsest attests to the rapid tectonic shifts midcentury gay spaces experienced. It hearkens to the community’s ability to reinvent and reconsolidate. Gay resilience and resistance are further demonstrated by post-Stonewall changes in the structure and content of The Address Book.

Throughout the 1970s, The Address Book’s size swelled. More of the rainbow brightened its covers. Full-page ads for gay-friendly Mexican restaurants, Turkish baths, and leather goods shops began interrupting the entries, and the emergence of daytime institutions, like women’s bookstores, showed that homosexuals were marching out of the twilight. The guidebook also began locating specific public cruising spots, like “Griffith Park – nr. Golf Course, E of Greek of Theatre,” about which John Rechy, author of gay memoir “City of Night,” sang praises: “No other city [in the United States]…had a daytime scene as thriving as Los Angeles in Griffith Park.”

The longevity of entries also grows. Locations are printed and reprinted, precluding red lines, Wite-out, and new place names. Long Beach’s Mine Shaft, which is nestled among other gay bars on Broadway, first crops up in the ’70s. One can still play Joan Jett on the Mine Shaft’s jukebox, grab a pool cue, and cruise flannel-clad bears beneath the low ceiling. The same goes for Ocean Avenue’s Club Ripples, where one can catch drag performer Lady Caca running to the toilet, two-ply stuck to her spike heels, in scatological spoof of Steffani Germanotta.

During the ’70s, The Address Book became a gay institution unto itself. Sharon Raphael, a retired Cal State Dominguez Hills professor and Long Beach resident, says, “Sisterhood bookstore was in Westwood. We found the Damron there.” The Damron. That’s how the Address Book came to be known and is known today. Raphael says, “One time, in the late ’70s, we travelled all the way up to Canada using the Damron, going to different women’s bookstores from San Francisco to Vancouver.”

These feminist bookstores have gone the way of the gay nightspots listed in the early guidebooks, but art continues to resurrect lost queer topography. The Address Book keeps inspiring Jauregui, who has created a new series of paintings based on “Disguised Ruins” titled “Piss Elegant / Some Motorcycle!” These will be shown at the Samuel Freeman Gallery in November. Jauregui sees his art and mapping as resistance and says, “ I want to position myself within this queer history. I inherited this history that I didn’t know anything about. I’m left thinking about this lineage. These ghosts.”

This article was originally published Oct. 25, 2016. It has been re-published in conjunction with the broadcast of Lost LA's "Coded Geographies" episode.