A Centuries-Old Legacy of Mutual Aid Lives On in Mexican American Communities

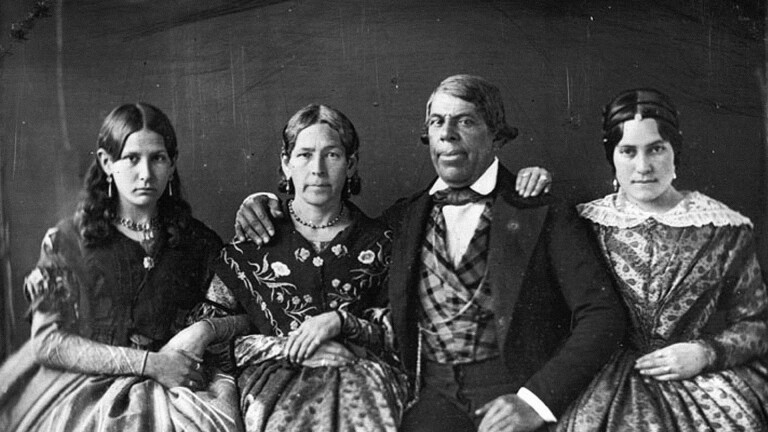

This story is published in collaboration with Picturing Mexican America.

When Ray Ricky Rivera, founder of Norwalk Brew House, joined forces with Brewjería and South Central Brewing Company to sell a specially made and marketed beer to benefit local street vendors, they may not have known they were following a centuries-old tradition of the Latinx community taking care of its neighbors.

Mutual aid societies or mutualistas popped up all over the Southwest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to provide cultural, economic and legal support to Mexican American immigrants. They opened schools to counter poor education offered in Latinx neighborhoods, provided medical and life insurance and fought for civil rights.

Today the mutualista spirit is alive and well as individuals and businesses find creative ways to help people who have suffered from financial hardship, illness, death of a loved one and ongoing food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonprofits and mutual aid societies from the Central Valley to Boyle Heights formed in the last 14 months including the COVID-19 Mutual Aid Network of Los Angeles, which raised a half million dollars to assist Angelenos with utility bills, funeral expenses and groceries.

Rivera, Brewjería and South Central Brewing Company set out to help street food vendors whose lives and livelihoods were affected by the pandemic with Lalo Alcaraz-illustrated cans of beer. They sold "Los Vendors" beer at Brewjería with some of the proceeds going to The Street Vendor Emergency Fund.

"It sold out in 24 hours," Rivera said. It was such a hit, they made another batch — "Los Car Washeros,"— to benefit local car washers, and another coming out in June, "Los Jornaleros," with proceeds going to the nonprofit NDLON, the National Day Laborer Organizing Unit.

The effort provided donations while also driving business to the breweries that, like much of the food and beverage industry, struggled over the last year to stay afloat.

Finding mutually beneficial solutions was the impetus for mutualistas created in the Southwest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to meet needs not provided by the United States government or other power structures. Early mutualistas in Texas and Arizona provided life insurance for Latinos who otherwise couldn't get it because of low income or racist business practices.

In 1918, several mutualistas formed in East Los Angeles to help Mexican immigrants find housing, employment, health care and build community, according to "Mutual Aid Societies in the Hispanic Southwest, a research reportby José A. Rivera, Ph.D, research scholar at the University of New Mexico.

While mutual aid societies can be found throughout history in European and Asian societies. Part of the motivation to create mutualistas in the Southwest — in addition to providing necessary social services — was to help keep the Mexican culture alive by organizing themed social events like festivals and picnics.

Santa Barbara's Confederación de Sociedades Mutualistas sponsored a Mexican Independence Day event in the 1920s that lasted three days, Julie Leininger Pycior wrote in her book "Democratic Renewal and the Mutual Aid Legacy of US Mexicans." One Santa Barbara chapter even had a baseball team. In Los Angeles, La Sociedad Hispano-Americana de Beneficia Mutua gave out loans, provided social services and sponsored a Cinco de Mayo Parade.

And the history goes back even further. Alianza Hispano-Americana — the largest mutualista founded in 1894 — had thousands of members and 269 chapters in big cities and small towns in California, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Texas with nearly $8 million in life insurance by 1939. Members didn't just join to get low-cost insurance and to meet new people, José Rivera wrote. Alianza helped striking miners negotiate for better wages and "assumed the function of a working man's union, persuading Mexican-American workers to come forward and challenge the managers of capital for better working conditions and fair wage increases."

During the 1920s, Alianza created a legal defense fund to help victims targeted because of their "national origin and/or economic status in life," José Rivera wrote. In the 1950s, Alianza brought legal challenges against segregated places like schools and public swimming pools.

As time went on, other groups looking to reach the Latinx community used the mutualista framework to organize. Los Angeles labor activists Soledad "Chole" Alatorre and Bert Corona based the group they started in the 1960s, Hermandad Mexicana Nacional (HMN), on mutual aid groups of the early 1900s, Pycior wrote.

...The first order of business was to answer the needs of the undocumented — to teach workers how to organize, how to do what was mutually necessary for them, and it was done under the obligation of mutual aid: the one that knows, teaches the other one," Alatorre said in Pycior's book. "'He who has gone to obtain his unemployment insurance teaches the one going for the first time — and with Social Security … immigration forms...this happened daily.

Through HMN and the other group Alatorre and Corona formed, Centro de Acción Social Autónoma, they fought for immigration reform and the rights of undocumented workers.

That long history of looking out for the community is embodied in the several groups trying to help undocumented workers that sprang into action during COVID. Even though more than two-thirds of undocumented immigrant workers served on the frontline of the pandemic, they were ineligible for most forms of federal aid.

That bothered Boyle Heights business partners Othón Nolasco and Damian Diaz.

Days after Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that the city was going into lockdown in March of 2020, Nolasco and Diaz noticed an influx of online fundraisers for front of the house restaurant and bar staff — servers and bartenders. They wondered how the back of house restaurant workers, many of whom were undocumented, were going to feed their families and pay their bills.

"It became obvious to us that the system is very, very unfair," Nolasco said. "They pay into the unemployment insurance, the EDD system — every week in their paychecks they get taxed and they were going to get no benefit from it."

Nolasco and Diaz, who are both sons of Mexican immigrants, immediately created No Us Without You LAto feed 30 families. They used their own money the first week and then friends and colleagues got on board to donate, volunteer and let them know about other workers — from hotel staff to street food vendors to mariachis — who needed assistance. Now, their nonprofit feeds 1,673 families a week and has corporate donors to help. Recently, the United Way of Los Angeles gave them $50,000 in grants to be distributed to at-risk families.

Most of the people they feed worked two to three jobs before the pandemic just to survive. Those jobs aren't coming back anytime soon. And food insecurity in Los Angeles isn't going away, Nolasco said, and neither is No Us Without You LA.

"That's just how we were raised, to never forget where we're from and make sure that our family's taken care of and to help others," Nolasco said. "Both of our families have these amazing stories that they pass on to us about helping those in need and that can never be something you can overlook or not have time for."