The Devil Wind: A Brief History of the Santa Anas

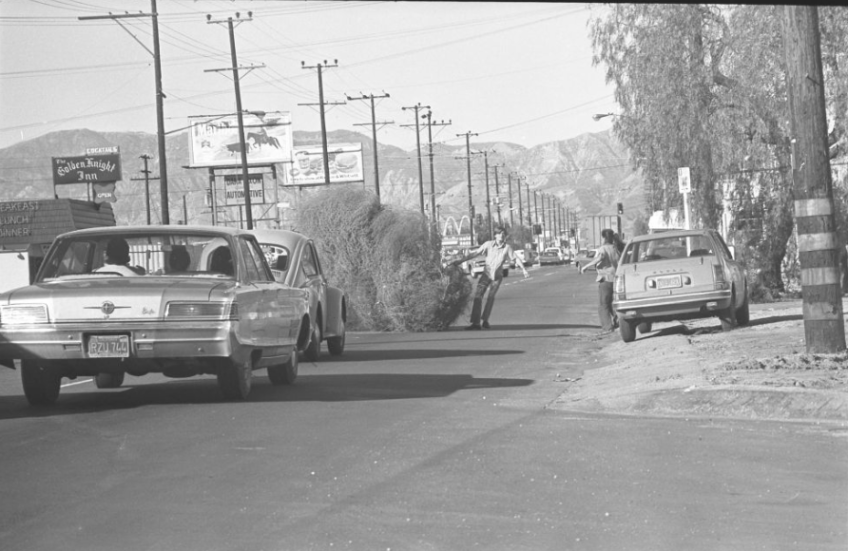

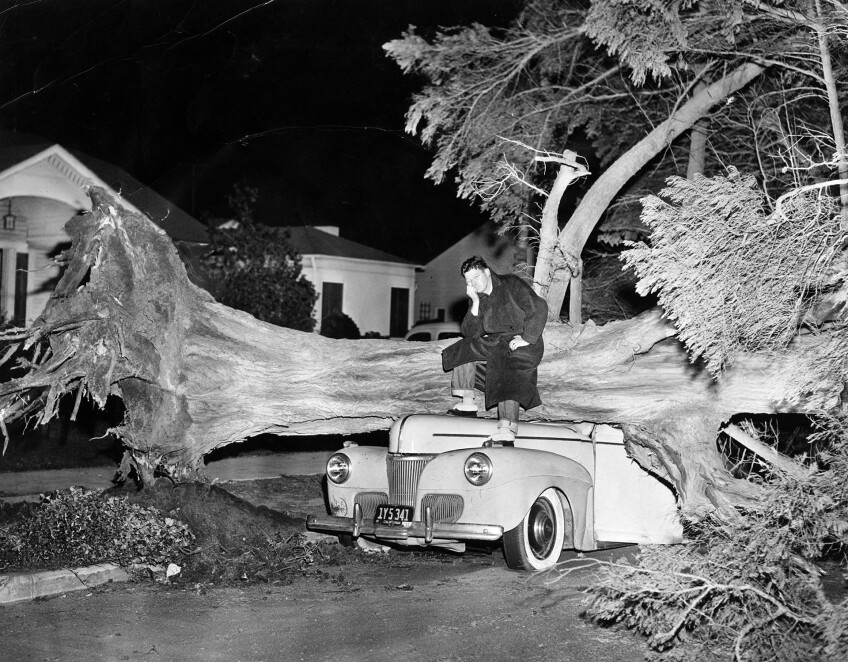

Triggering allergies, fraying nerves, and alarming fire-prone communities, the Santa Ana winds have long been a fact of life in Southern California – the unadvertised price residents pay for the region's otherwise idyllic weather. And though the winds – which arrive in the fall, peak in December, and depart in the spring -- are invisible to photographers' lenses, cameras have recorded the destruction this recurrent weather phenomenon has wrought throughout the region's history.

Southern California usually sits in a delicate climatic balance. On one side, the chilly waters of the Pacific, transported from Alaska via the California Current, stabilize air temperatures and provide a ready source of moisture. On the other, a palisade of mountains blocks the extremes of the desert from coastal communities.

The Santa Anas upset that balance, ushering in hot, dry, desert-like conditions. But while the Santa Anas are often called desert winds, the term is misleading; the winds are not simply blowing desert air over Southern California's coastal plain. Instead, Santa Anas result from a cool, dry air mass that hovers over the continental interior of the American West. When that air descends from the higher-elevation basins to sea level, it warms and becomes even drier. (A similar phenomenon, termed a föhn wind, warms Central Europe.) Funneled through the Cajon and San Gorgonio passes, the moving air gains speed and destructive power.

Local lore offers several competing explanations for how the winds got their name.

One holds that the name finds its provenance in an Indian word for wind, which Spanish missionaries, detecting an evil presence in the winds, liked for its homonymy with "Satan." Another claims a saintly rather than devilish origin of the name: while camping in present-day Orange County in 1769, the Portola expedition supposedly encountered a fierce windstorm on Saint Ann's Day. Yet another suggests Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna as the winds' eponym.

Scholars who have looked into the name's origins generally agree that it derives from Santa Ana Canyon, the portal where the Santa Ana River -- as well as a congested Riverside (CA-91) Freeway -- leaves Riverside County and enters Orange County. When the Santa Anas blow, winds can reach exceptional speeds in this narrow gap between the Puente Hills and Santa Ana Mountains.

Winds were ferocious in Santa Ana Canyon on the night of January 6, 1847, when U.S. forces under Commodore Robert Stockton camped near the canyon during their conquest of Los Angeles. Stockton's diary describes their ordeal:

Taking advantage of a deep ditch for one face of the camp, it was laid off in a very defensible position between the town and the river, expecting the men would have an undisturbed night's rest...In this hope we were mistaken. The wind blew a hurricane (something unusual in this part of California), and the atmosphere was filled with particles of fine dust, so that one could not see and but with difficulty breathe.

If the windstorm Stockton and his troops endured was the source of the name, little evidence exists in the historical record. Subsequent written descriptions lacked the winds' distinctive name, referring to them simply as "northeasters." It was not until Nov. 15, 1880 -- nearly 37 years after Stockton jotted down his observations -- that the earliest-known written reference to the "Santa Anas" appeared in an article in the Los Angeles Evening Express titled "The Philosophy of Sandstorms."

Whatever the origins of their name, the winds have made memorable appearances in the region's literature.

In "Two Years Before the Mast," Richard Henry Dana recounts a "violent northeaster" in 1836 that forced his ship, the Pilgrim, to leave its anchorage in San Pedro and seek refuge in the leeside of Santa Catalina Island.

In his memoir, "Sixty Years in Southern California," the Jewish-German Angeleno Harris Newmark recalls an 1865 windstorm that "struck Los Angeles amidships, unroofing many houses and blowing down orchards."

Agriculture dominated the Southern California landscape for much of its history, and the prospect of Santa Ana winds haunted farmers and orange growers. When the winds came, they destroyed crops and suffocated urbanized areas with dust -- a phenomenon that fed the growing misconception of Los Angeles as a desert.

In John Fante's "Ask the Dust," Arturo Bandini looks out the window of his Bunker Hill apartment and observes a palm tree, "its crusted trunk choked with dust and sand that blew in from the Mojave and Santa Ana deserts."

By the time Raymond Chandler captured the winds in his 1938 story "Red Wind," they menaced not only crops but civil order, as well:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that, every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husband's necks. Anything can happen.

Joan Didion picked up where Chandler left off in 1965. Her "Los Angeles Notebook," later collected in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," is perhaps the classic literary treatment of the Santa Ana winds:

The baby frets. The maid sulks. I rekindle a waning argument with the telephone company, then cut my losses and lie down, given over to whatever is in the air. To live with the Santa Ana is to accept, consciously or unconsciously, a deeply mechanistic view of human behavior. ...[T]he violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.