A Brief History of Palm Trees in Southern California

If you close your eyes and imagine a typical Southern California landscape, chances are that you've pictured at least one palm tree, if not several, rising from the ground. But despite the diversity and ubiquity of palms in the Los Angeles area, only one species—Washingtonia filifera, the California fan palm—is native to California. All of L.A.'s other palm species, from the slender Mexican fan palms that line so many L.A. boulevards to the feather-topped Canary Island date palm, have been imported.

The transcontinental railroad reached Southern California in 1876, fueling a boom that transformed a remote cowtown into a city. Watch Lost LA "Semi-Tropical L.A." to learn about how Los Angeles marketed itself as a “semi-tropical” destination to achieve that.

Although they conjure the image of Los Angeles as desert oasis, L.A.'s palm trees owe their iconic status more to Southern California's turn-of-the-century cultural aspirations and engineering feats than to the region's natural ecology. Though watered in some places by perennial streams like the Los Angeles River, Southern California's pre-1492 landscape was decidedly semi-arid, a patchwork of grassland, chaparral, sage scrub, and oak woodland. As monocots, palms are actually more closely related to grasses than they are to woody deciduous trees. They need an abundance of water in the soil to grow successfully, and so they—like the manicured lawns they often adorn—rely on the vast amounts of water that Southern California imports from distant watersheds.

Southern California's native palms grow far away from Los Angeles, in spring-fed Colorado Desert oases tucked deep inside steep mountain ravines. Centuries before palms were cultivated for their horticultural value, the Cahuilla Indians used these Washingtonia filifera as a natural resource, eating the fruit and weaving the fronds into baskets and roofing.

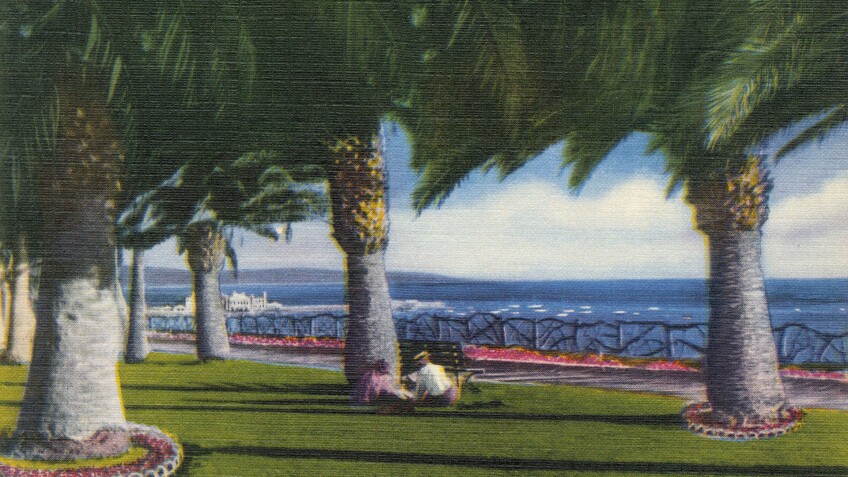

California's eighteenth century Franciscan missionaries were the first to plant palms ornamentally, perhaps in reference to the tree's biblical associations. But it was not until Southern California's turn-of-the-twentieth-century gardening craze that the region's leisure class introduced the palm as the region's preeminent decorative plant. Providing neither shade nor marketable fruit, the palm was entirely ornamental. Its exotic associations helped reinforce what Kevin Starr describes in "Inventing the Dream" as "Southern California's turn-of-the-century conviction that it was America's Mediterranean littoral, its Latin shore, sunny and palm-guarded."

Although they lacked the zealous advocacy that Abbot Kinney's eucalyptus trees enjoyed, palm trees soon appeared throughout Los Angeles, from the front yards of the mansions along Figueroa Street to public spaces like Pershing Square, Eastlake and Westlake Park, and the historic central plaza near Olvera Street.

The 1930s witnessed the largest concerted effort to plant palm trees in Los Angeles. Pasadena planted palms at 100 feet intervals along Colorado Boulevard and considered renaming the thoroughfare the "Street of a Thousand Palms." In Venice, gardening enthusiasts planted 200 Washingtonia robusta (Mexican fan) palms on Washington Boulevard to celebrate the bicentennial of the nation's first president, for whom the tree was named. The Los Angeles Times regularly printed articles praising the palms' "magical" qualities and comparing the trees to "plumed knights."

In 1931 alone, Los Angeles' forestry division planted more than 25,000 palm trees, many of them still swaying above the city's boulevards today. This massive planting effort—conceived by the city's first forestry chief, L. Glenn Hall—is often characterized as a beautification project for the 1932 Olympic games. But impressing foreign athletes actually played less of a role than did getting L.A.'s unemployed back to work; the $100,000 program that planted some 40,000 trees in total was part of a larger unemployment relief program, funded by a $5 million bond issue. Beginning in March 1931, the city put 400 unemployed men to work planting trees alongside 150 miles of city boulevards. Mexican fan palms—then costing only $3.60 each—were spaced 40 to 50 feet apart.

Today, many of the palm trees planted in the 1930s are nearing the end of their natural life spans. The recent arrival of the red palm weevil—known to devastate palm populations across the world—augurs poorly for the fate of younger trees. The L.A. Department of Water and Power has indicated that as the city's palm trees die, most will not be replaced with new palms but with trees more adapted to the region's semi-arid climate, requiring less water and offering more shade.

Like the palm, the orange tree was also once a ubiquitous feature of the landscape and a symbol loaded with cultural meaning. In fact, early-twentieth-century postcards and other promotional materials often featured scenes of tranquil orange groves framed by exotic palms. Those groves have largely vanished from Southern California. It remains to be seen whether the palm's future will be any different.