15 Places in L.A. Where LGBTQ History Was Made

The 1969 Stonewall Uprising in New York is widely regarded as the beginning of the Gay Civil Rights Movement, but the heart of the movement, and what we know as "gay culture" has strong roots in Los Angeles. There are many destinations that have a rich history in the fight for LGBTQ liberation in Los Angeles. Here are just a few, and we invite you to tell us more.

Cooper Do-nuts

Cooper Do-nuts was a 24-hour café popular among the gay, lesbian and trans communities during the 1950s and '60s. Nestled in between two gay bars, the Harold's and the Waldorf, the café was one of few establishments in the city to welcome trans customers at a time when many gay and lesbian bars turned them away in fear of LAPD targeting and persecuting transgender and gender non-conforming Angelenos.

One form of LAPD's routine harassment included targeting well-known LGBTQ spaces and demanding identification from gender non-conforming patrons. If their outward gender presentation didn't match their ID, they would be arrested. On May 1959, LAPD officers arrested five Cooper Do-nuts patrons — two drag queens, two male sex workers and one gay man — through such tactics. As the patrons were ushered into a police car, a group of lesbians, transgender women, drag queens and gay men rushed to the streets, resisted the arrests, throwing donuts, paper plates and coffee cups. There are no official reports or news coverage of the event, but author and eye-witness John Rechy recalls the "street was bustling with disobedience."

The Black Cat Tavern

The Black Cat Tavern was the site of a brutal police raid that incited one of the first demonstrations in the U.S. protesting police brutality against the LGBTQ community. On New Year’s Day 1967, as the clock struck midnight and rang in the new year, plain-clothed LAPD officers raided the tavern, beating and arresting 14 people who were charged with "lewd conduct" for same-sex kissing. Then, on Feb. 11, 1967, demonstrators gathered outside the Black Cat to protest the police raid, preceding New York’s Stonewall Uprising by two years. Today, the Black Cat is a recognized Historic-Cultural Monument by the City of Los Angeles and continues to be a popular spot for classic cocktails and American tavern food.

City of West Hollywood

Before West Hollywood was designated an official city in 1984, the area was an unincorporated region of Los Angeles County, existing outside the jurisdiction of the Los Angeles Police Department. Tucked away from LAPD’s watchful eye, the area attracted a flourishing queer community seeking refuge from the police department’s draconian approach to policing "homosexual offenses."

In the mid 1980s, as rent prices skyrocketed and the expiration of L.A.’s rent-control protections threatened to price out longtime residents, a coalition of gay men and Russian Jewish émigrés banded together to officially incorporate the area as the City of West Hollywood. The coalition immediately passed a series of rent control measures and elected a city council with an openly gay majority, solidifying West Hollywood’s status as a visible symbol of gay Los Angeles.

Pershing Square

Pershing Square was a meeting ground for gay men for much of the early 20th century, located at the heart of "The Run" — a circuit of gay-friendly establishments and cruising spots in the 1920s through the '80s. Notable spots in "The Run" were the Central Library, the bar at the Biltmore Hotel and the Subway Terminal Building’s bathrooms. In 1951, the city cleared the area for a three-level parking garage, gutting the trees that once made up a lush wooded area that facilitated private rendezvous among men.

Studio One Night Club

Studio One was a popular bar and disco, well-known for its young crowd and entertainment — from cabaret performances to theater. Founded in the early 1970s by part-owner Scott Forbes, dubbed the "Disco King" by the Los Angeles Times in a 1976 feature, the dance club operated in West Hollywood until 1988 when it was bought and renamed "Axis." Though the club is certainly associated with its prominence in the gay rights movement, Studio One has a complicated history of intense exclusivity. Many criticized the club for catering to white gay men and denying Black, Chicano and women patrons at the entrance through exclusionary door policies and classist dress codes.

Controversy surrounding the night club's exclusivity reached a peak in 1975 when the Gay Community Mobilization Committee made efforts to shut down exclusive policies by sending letters of protest and organizing community boycotts. Despite the committee's efforts, Studio One stayed packed and busy for years even while the presence of picketers outside the club became commonplace.

Circus Disco / Arena Night Club

Circus Disco played an important role in the Latinx LGBTQ community as the oldest and longest running LGBTQ Latinx nightclub in Hollywood and Los Angeles. Opened in 1974 by Gene La Pietra and Ermilio "Ed" Lemos, the club served patrons of all races, orientations and gender identities as an alternative to then-exclusionary nightclubs of West Hollywood. Over time, Circus Disco quickly developed a reputation, along with its neighbor Arena and Jewel's Catch One, as one of the few gay clubs in L.A. without a dress code or racist door policies.

An important aspect of Circus Disco was its primarily Latinx identity, owned by Latinx entrepreneurs and maintaining a loyal clientele of Latinx gay men. The disco frequently organized themed events like Western night, dress-in-uniform night, pajama party and "A Latino Happening at Circus Disco." Outside the themed parties, Circus Disco also played an important role in political organizing and coalition building. Fundraising nights, benefits and galas were commonplace at Circus Disco, raising money for organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation Gay Rights Chapter, the Norton Sound 8, and even creating a scholarship fund to benefit young gay men and women. Circus Disco closed in 2016, but the giant clown mouth entrance that welcomed hundreds of patrons for over four decades still remains.

Jewel's Catch One

Jewel's Catch One was one of the first Black discos in the U.S. and the longest running gay dance bar in L.A. Opened in 1973 by Jewel Thais-Williams, the bar sought to serve queer people of color who were often unwelcome at other nightclubs like West Hollywood's Studio One. At the time, Studio One was known to hassle Black patrons for multiple forms of ID to be allowed inside the venue and they certainly weren't alone among West Hollywood bars to practice racist and misogynist door policies.

Thais-Williams, a Black lesbian, purchased what was then the Diana Club in a white neighborhood and received threats from authorities, police and general public. The club remained open, however, and found success, attracting celebrities like Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Madonna and Rick James. But aside from the disco's bustling scene and dazzling celebrity appearances, Jewel's Catch One served as a community hub, offering its space for political organizations to have community meetings. During the AIDS crisis, Thais-Williams hosted fundraisers at the disco to support Black gay men in the community who were disproportionately impacted. The Catch closed in 2005 and Thais-Williams sold the building in September 2014.

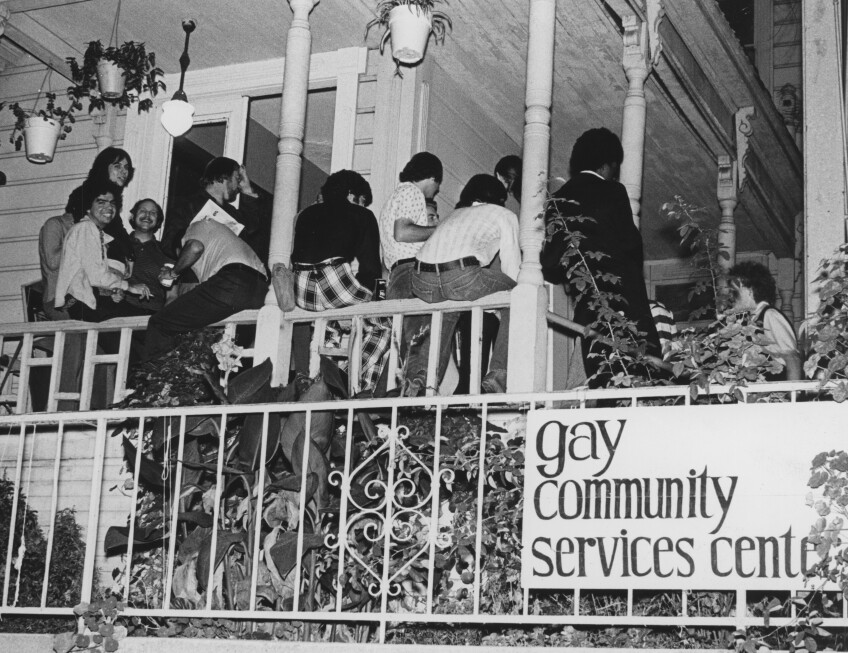

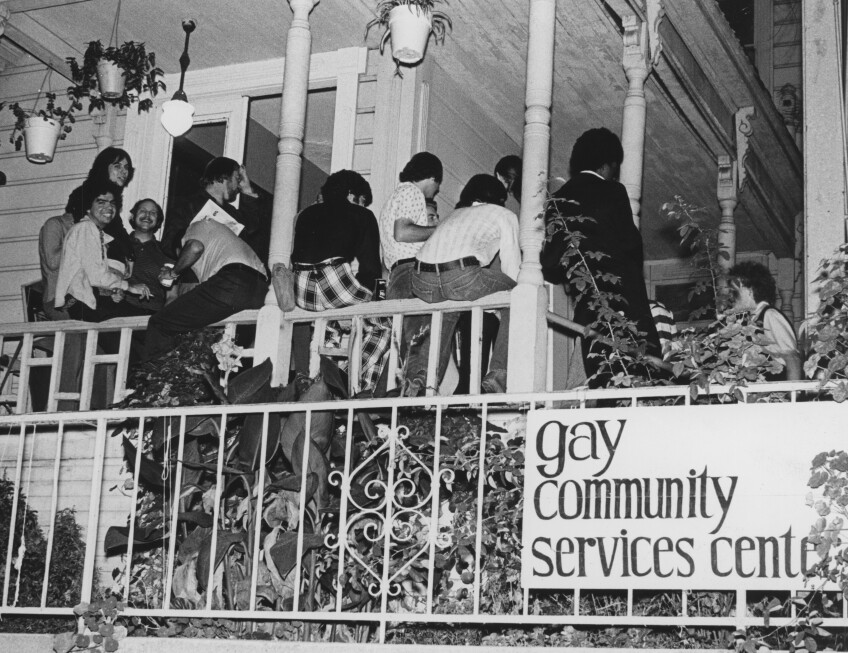

L.A. LGBT Center

The Los Angeles LGBT Center has cared for, championed and celebrated L.A.'s LGBTQ community since 1969. The Center began as a loose association of activists volunteering to provide mental health support and referrals for LGBTQ individuals. From their work came the idea of a Gay Community Center. Among the center's founding group of organizers was gay and lesbian rights activist Morris Kight.

The group opened its first "Liberation House" for homeless LGBTQ individuals and opened its headquarters at 1614 Wilshire Boulevard in 1971, providing services like counseling, family services and a venereal disease clinic. A year later, the center would establish the first lesbian health clinic in the world, staffed by volunteer lesbian medical professionals. In 1974, after being initially denied non-profit status by the IRS, the center won its appeal and became the first openly LGBTQ organization to receive tax-exempt status. The Los Angeles LGBT Center now operates nine facilities in Los Angeles, offering services in health, housing, social services education, leadership and advocacy.

Griffith Park

Griffith Park was one of L.A.’s most notorious spots for men to cruise after dark. But perhaps Griffith Park is more well-known in L.A. queer history as the site of the 1968 "Gay-Ins" organized by the Gay Liberation Front. "Gay-Ins," a riff on the hippie “be-ins” at the time, were gatherings that combined education and recreation, starting with a primer on police harassment and ending with a bar crawl that ran late into the evening.

Hollywood Gay Pride Parade

On June 28, 1970, the first LGBT pride parade in Los Angeles stepped off the corner of Hollywood Blvd. and McCadden Place, powered by over 2,000 people on foot and floats. The event was organized in early 1970 by Rev. Troy Perry, Rev. Bob Humphries and Morris Kight, a founding organizer at L.A. LGBT Center, to memorialize New York's Stonewall Uprising in Los Angeles, with simultaneous events in New York, Chicago and San Francisco.

Barney's Beanery

Barney's Beanery is remembered for its history of hostility towards the LGBTQ community. Located in West Hollywood, the gritty roadhouse was well-known for a sign mounted over the bar reading, "Fagots stay out" (sic). The sign, installed by then-owner John "Barney" Anthony, hung on the wall as early as the 1940s but it wasn't until the 1970s that LGBTQ community leaders like Rev. Troy Perry and Gay Liberation Front founder Morris Kight pressured the new owner, Irwin Held, to take down the sign; Held refused.

What followed were persistent protests outside Barney's Beanery which led to the temporary removal of the sign only for it to be remounted along with more hostile signage. The hateful signs were permanently taken down in 1985 when West Hollywood became an official incorporated city and adopted an anti-discriminatory ordinance.

Redz Bar

Redz Bar represents an important intersection of race, class, gender and sexual identity as one of few lesbian bars to cater to Latinas. Redz, originally Redheads, opened in Boyle Heights in the 1950s, catering to a predominantly Mexican and Mexican American clientele at a time when working-class lesbian bars were on the rise around Los Angeles, particularly in Westlake and North Hollywood. Redz Bar closed in 2015.

Merced House / Merced Theatre

The Merced was the first building in Los Angeles built for theater arts before it closed in 1887 due to a local outbreak of smallpox. It re-opened as an informal entertainment venue. The Merced quickly became popular for its masked balls, becoming a safe gathering place for LGBTQ individuals who were able to socialize under the safety of concealed identities. The masquerade balls also created a safe space for attendees to dress outside of the constraints of gender without fear of prosecution, serving as precursors to drag balls of the 1930s, '40s and '50s.

The location was later converted by Frederick Purssord into a lodging house for queer men. The Merced still stands on Main St. as one of the few remaining locations in Los Angeles that signify early 19th century L.A. queer history.

The Hay House / Mattachine Steps

Harry Hay was a gay rights activist, communist and labor advocate who founded one of the earliest gay rights activist groups in the U.S., the Mattachine Society. Starting as "Bachelor's Anonymous," the group was originally composed of Hay, his partner and five other gay male friends who would congregate at Hay's house in Silver Lake. The organization grew steadily and quietly in Hay's home, organizing around LGBTQ+ issues and publishing the Mattachine Review, a widely circulated magazine by and for the gay and lesbian community. The Mattachine Society would later grow outside of L.A., branching out to other cities across the country. In 2012, the concrete steps adjacent to Hay's home were named the Mattachine Steps, commemorating his contributions to the gay rights movement and honoring his home — what some consider "the birthplace of the gay rights movement."

Julian Eltinge Residence

Julian Eltinge, renowned for his vaudeville female impersonations and often regarded as America's first celebrated drag performer, lived in the Villa Capistrano in Silver Lake at the height of his silent film career in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Spanish revival style hilltop estate was the backdrop of frequent lavish parties for Eltinge's Hollywood peers.

The silent film industry provided a safe space for those who identified as non-heterosexual, like Eltinge. Relaxed attitudes around homosexuality at the time could be attributed to the influx of actors and performers arriving in Hollywood from Europe, where perceptions of sexuality and gender identity were more lenient.