Yesterday's Water System Back in Los Angeles

If the 1974 film "Chinatown" has taught us anything, it's that water is a big deal in Los Angeles, then and now. Water helped Los Angeles grow into the bustling metropolis it is today. Now, artist Lauren Bon is giving Los Angeles a glimpse at history with Siempre Agua.

Slated to be built in time for the centennial celebration of the Los Angeles Aqueduct's opening in November 2013, Siempre Agua is a three-part piece that consists of the zanja, represented by the 72-inch diameter tunnel buried 30 feet below the ground that will divert L.A river water; LA Noria, or 60-foot water wheel; and the Delta of Mt. Whitney, a 2-acre wetland area on the Los Angeles State Historic Park that will receive the diverted water.

When finished, water from the Los Angeles River would be carried through the tunnel, disinfected with ultra-violet light and distributed for non-potable uses in and around the State Park, including a man-made habitat on State Park property. It is designed help alleviate annual water demands for the park, representing a savings of $101,000 each year in water costs.

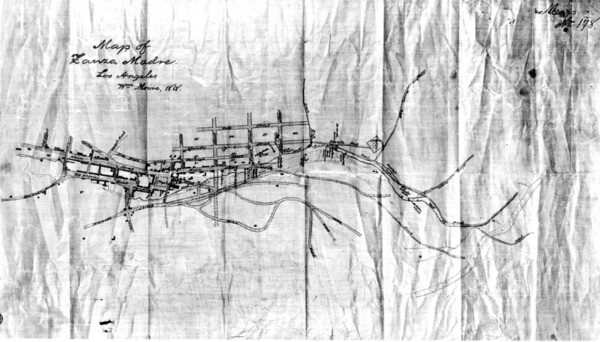

It is not the first time a system like this has been used in Los Angeles. According to Blake Gumprecht's "The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth," the zanja system, a network of ditches that diverted water from Los Angeles River into the new Pueblo de Los Angeles by gravity, has been a part of L.A. as long as it had been in existence.

Felipe de Neve, the first governor of California, selected the site that would become modern day Los Angeles because it was "a land suitable for irrigation." The first settlers in 1781 were farmers. They were responsible for the building and maintaining a dam, as well as the ditches that would carry water for agriculture.

Unlike now, L.A. was a sleepy agricultural town that with the help of the zanjas became California's first wine-producing center (yes, even before Napa). In 1850, "Los Angeles was the number one wine-making county in the nation, producing 57,355 gallons, a third more than its nearest competitor," wrote Gumprecht. Farmers eventually diversified to plant the fruit-bearing trees like oranges and lemons that are staples in the Los Angeles landscape today.

As the city grew, so did its demand for water, and the zanja system. By the time 1849 came around, zanjas and its water wheels reportedly powered the first flourmill in Los Angeles, as well as a local newspaper's printing press.

Under U.S. rule, zanjas became regulated, though crudely and inefficiently. An official was put in charge, fees were levied and permits issued. As more newcomers poured into Los Angeles, the demand for water increased and zanjas soon couldn't keep up with the demand. Eventually, open ditches were abandoned, to be replaced by pumps, closed pipes and regulated systems. Soon, it was as if zanjas never existed. But come November next year that won't be the case.

Siempre Agua is ambitious, but it's a challenge right up Bon's alley. The artist was the mastermind behind the Not a Cornfield project some years back. Not only that, but Bon is working with a team of experts to help her realize this project. Geosyntec is Bon's engineering firm, and separate companies are handling the actual tunneling, water wheel fabrication and environmental permitting.

Despite its grand plans, Siempre Agua is still very much a work in progress, says Mark Hanna of Geosyntec, "We were going over some design considerations and it turned into a healthy debate on how this thing is going to look and operate."

The team's biggest challenge is perhaps how to revive a forgotten technology and make sure that it works. "We are trying to get every bit of energy out of the river that we can," said Hanna in a phone interview. During the water diversion, small details can make a big difference. "You want that water to flow through as smoothly as possible. From the blades of the wheel to the ball bearings on which the wheel is going to spin, I'm working to minimize all the losses that could occur."

Bon is exploring using different materials for each part of the system. Blades could be made out high-strength recycled plastic. The hub and support structure could be made of steel. The rims could be made of aluminum, theorizes the artist and her team. But all of these are subject to cost and resiliency toward water. In response to how long this project will last, Hanna says: "We want this thing to last a hundred years."

Permitting is also undertaking. The project requires permits from ten different agencies: one federal, two state, two regional and five local agencies are included in the planning. When talking about the river, one needs to talk to the Army Corps, who oversee the channel; the Department of Fish and Game, who looks over the streams that Bon's team is seeking to alter; the L.A. Department of Water and Power needs to be notified because the project is set to go underneath its power line easements; the Department of Public Health has to be in the know because of the project's water re-use aspects. "The list goes on and on," said Hanna. But if all goes well, come November 2013, Siempre Agua's big wheels will turn smoothly, reminding Angelinos of where we've been, how we can work with the water around us, and how best we can manage our water in the future.

[Update 8/31: Earlier version noted that Hanna is exploring using different materials. It is Bon and her team who are exploring.]