Why are Green Groups So White? A Talk With George Sánchez-Tello

The common stereotype of environmental activists would tell you that they're all either high-priced lawyers or trust fund hippies. That hasn't been true for decades, if it ever was at all. Our series This Is What Green Looks Like profiles Californian environmental activists from diverse communities and walks of life, bringing you stories of your neighbors campaigning to protect the planet.

Somewhere near the start of every term in his environmental justice class at Cal State L.A., George Sánchez-Tello asks students to close their eyes and imagine an environmentalist. “What do you picture?” he asks his 45 students – all students of color this semester, some of whom are standing because there aren’t enough seats for them in the classroom. And every time, the students’ responses are more or less the same: cargo shorts, hiking boots, and a Toyota Prius always make the list.

As he asks students to be more descriptive, a fuller image emerges: The environmentalist in the students’ imagination is almost always a man, and that man is always white. None of the students in Sánchez-Tello’s class ever imagine an environmentalist that looks like them.

What the students are articulating, explains Sánchez-Tello, is a set of consumer choices – the clothes you buy, the car you drive – that’s largely based on one’s access to wealth. He pushes back and invites his students to dig a little deeper, asking them to describe their family’s gardens (including ranchos in Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala they may have heard about), their recycling practices, and their relationship to water. “Together, we quickly establish that they have an environmental history,” says Sánchez-Tello. “What they don’t use is the word ‘environmentalist’ or ‘environmentalism’ to describe that.”

That’s not just the case in Sánchez-Tello’s classroom. A 2015 survey of registered Latinx voters indicated that while immigration reform was extremely or very important for 80 percent of respondents, environmental issues like strengthening the Clean Water Act, reducing smog, and increasing water conservation polled five to ten points higher. The survey, conducted by LatinoDecisions on behalf of Earthjustice and Green Latinos, reveals that 82 percent wanted their families to learn more about protecting the environment – yet fewer than one in four had ever been contacted by an environmental organization. And, despite numbers that reflect an overwhelming interest in protecting the environment, only 18 percent described themselves as environmentalists. The majority, 62 percent, identified as “someone who cares about the environment, without using the term.”

82 percent of Latinx voters wanted their families to learn more about protecting the environment. Fewer than one in four had ever been contacted by an environmental organization.

The LatinoDecisions survey results pose a challenge for white-dominated environmental organizations in a demographically-changing United States. Sánchez-Tello, meanwhile, is teaching in Los Angeles, where white people make up less than 30 percent of the population. Despite a multi-generational investment in caring for the environment, Sánchez-Tello says his students will inevitably picture a white person from the suburbs as an environmentalist before they identify themselves as one.

Sánchez-Tello, who’s previously worked as a journalist, started the imagine-an-environmentalist exercise when he was working with The Wilderness Society’s San Gabriel Mountains Forever campaign. The answers always came back the same: the environmentalist is almost always a white man sporting dreadlocks, hiking boots, and a Prius. Sánchez-Tello began working with The Wilderness Society, a land conservation group not exactly known for its diversity, while he was in graduate school at Cal State Northridge working on a master’s degree in Chicano Studies. His thesis chair had a connection at The Wilderness Society and encouraged him to apply.

“I literally laughed,” he recalls. “I told her, ‘I’ve never done anything in the environment, I don’t have anything like that on my resume, and I don’t even identify with that word.’” Back in 2010 Sánchez-Tello, who grew up as a Boy Scout in Arcadia hiking and camping in the San Gabriel Mountains in his backyard, was not unlike his own students today: connected to the land, but unlikely to identify as someone who had anything to do with the wilderness. But he needed a job, so he applied. He did land an interview but didn’t get the fellowship that was initially being offered.

Nevertheless, Sánchez-Tello was asked back to apply for another position. He was hired to create an organizing training program to serve a coalition, housed within The Wilderness Society; he also focused on creating a leadership academy that served the communities the trainees came from. The organizer toolbox he helped develop lends itself to responding to everything from environmental justice to police abuse. To this day, the leadership academy that Sánchez-Tello started overwhelmingly engages with young Latinxs – more than half are women, and more than half are immigrants.

Those are inspiring numbers for any leadership academy, particularly one that’s tied to the environment. He credits part of that to a supervisor who treasured that Sánchez-Tello arrived to the organization with a different worldview – one that was critical of groups like The Wilderness Society but also willing to talk about equity and inclusion. Yet when I asked Sánchez-Tello, who left the organization in 2015, how much The Wilderness Society’s own demographics changed since he worked first worked there in 2010, he takes a long breath and an even longer pause. The answer is that he's not sure whether the organization has more people of color now than it did when he started there seven years ago. It might even have less.

When colleagues would ask Sánchez-Tello how the organization could arrive at racial equity, he would answer, “You choose to get there.”

Sánchez-Tello says the allies he had within the organization all regret what happened – that the explicit understanding around the need for equity never materialized into a change in the organization’s makeup. When colleagues would ask Sánchez-Tello how the organization could arrive at racial equity, he says he would always answer, “You choose to get there.”

He notes that 20 years ago, The Wilderness Society was mostly made up of men, but that now there are women at every level of leadership (though not women of color). The fundamental change that got white women on board occurred because the organization made a decision to make it happen. The Wilderness Society isn't alone here. A recent study reveals that out of 493 staffers hired by a total of 191 conservation groups between 2011 and 2014, only 12.8 percent were people of color. The Green 2.0 study points out, "Ethnic minorities are grossly underrepresented in the leadership of environmental organizations."

Sánchez-Tello adds that Trump’s victory also means that, as one colleague told him, “The goal now is to lose as little as possible.” Sánchez-Tello says that defensive focus may mean that engaging communities of color, not just at The Wilderness Society but also across most white-led environmental organizations, could fall by the wayside under the current administration.

It’s a troubling gamble, both on the numbers side and on the moral argument: Big Green prioritizing legislative and regulatory gains at the cost of ignoring communities of color for another generation seems ill-advised at time when communities of color are growing in size and political importance. It also suggests that the way certain human beings interact with the environment continues to not only be undervalued, but also perhaps wholly unrecognized.

The white, Prius-driving, hiking boot-wearing environmentalist in Sánchez-Tello’s students’ imaginations regularly goes on 20-mile endurance hikes on state and federal park land. For people of color, the connection with the land might be different – but just as valuable. “It’s that abuelita who’s using runoff shower water to tend to her avocado tree in a backyard that’s otherwise encased in concrete,” says Sánchez-Tello.

Other stories that Sánchez-Tello notes don’t fit the official environmentalist narrative include the people who drive to the mountains (and never leave their cars) to look at the trees, as well as families that barbeque at the edge of a riverbed while a boom box blares. It also includes the father of five who works six days a week, packs a minivan with his family to get to the wilderness, and finds a quiet moment standing with his toes in the San Gabriel River with a beer in his hand. “For that moment, he is at peace,” says Sánchez-Tello. “Other people just see a crowded, loud, noisy environment, but for him, it’s solitude – and it’s unfair to discount that.”

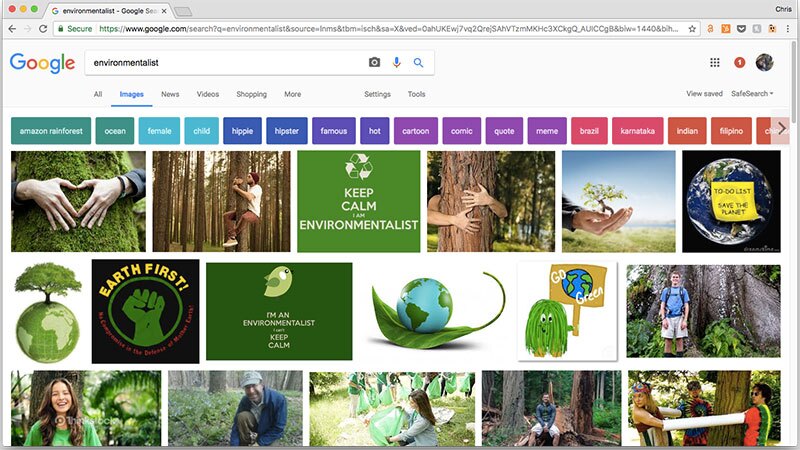

Take a moment yourself to close your eyes and picture an environmentalist. It might match what Sánchez-Tello’s students regularly describe, or it might match the white tree-hugger images prominently featured in a Google image search for the word “environmentalist”. Shaking those images, which are embedded into our imaginations by the mainstream white environmental culture that’s long left others out, is difficult. And it’s unclear if it’s even necessary. If Latinxs don’t identify as environmentalists, that’s fine. The real challenge is whether Big Green will prioritize and embrace the different experiences of people of color with the environment. It’s not an exaggeration to offer that the future of the planet, and the future of all of us who live on it, may very well depend on it.