When Residential Neighborhoods Are Rezoned for Warehouses

At a Valentine’s Day event last February called “We Love Bloomington,” framed photographs lined the walls of a small community center.

Stocky horses strode against the backdrop of a lush green hill. White clouds sailed across a blue sky over a bright red barn.

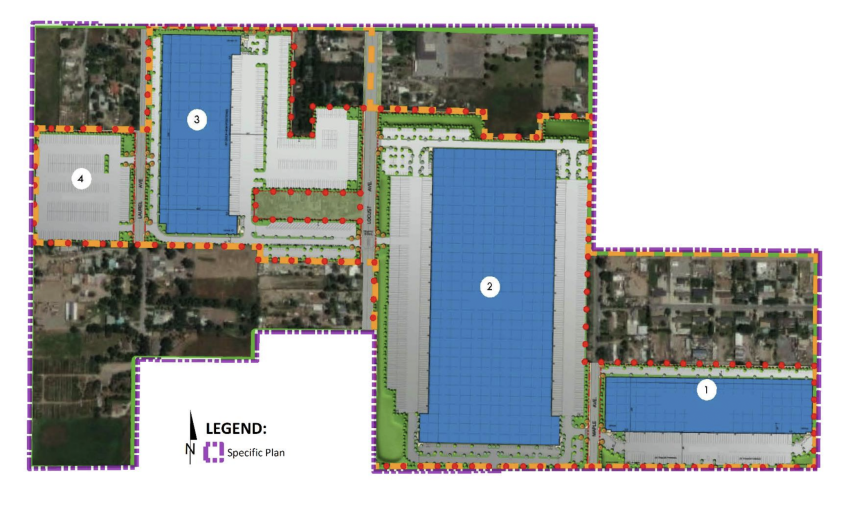

The images captured a pastoral landscape and lifestyle that the event’s organizer, Ana Carlos, contends is under threat as a 213-acre projectin Bloomington seeks to rezone low-density residential land for industrial use to make way for warehouses.

Bloomington is located in the heart of the Inland Empire, where warehouses have come to dominate much of the landscape over the last decade as e-commerce has supercharged a burgeoning logistics industry.

The region, just 60 miles inland from the ports of San Pedro Bay, is an integral link in the global supply chain. Inland Empire cities all along the 10, 15, and 60 freeways have developed robust warehouse corridors, easily accessible to diesel trucks hauling goods from the ports.

The new development in the San Bernardino County-run unincorporated community of Bloomington has prompted particular uproar from residents and environmental justice groups because it seeks to replace residential neighborhoods with warehouses, building within a stone’s throw of houses and schools.

The project, proposed in December 2020, would sit next to a high school and displace about 200 people, according to activists, though none of the property owners are being forced to sell. The developer, Howard Industrial Partners, told the San Bernardino Sun that 80 property owners in the project area have agreed to sell.

Nearby, a separate 259,000 square foot warehouse development was proposed last year.

Local leaders have exalted the revenue and economic benefits created by the expansion of warehousing, but many residents hold that they don’t outweigh the negative impacts, like the exacerbation of what ranks among the poorest air quality in the nation and the reconfiguration of whole neighborhoods.

A uniquely rural Bloomington on the verge of change

Only six warehouses — four near homes — have been built in Bloomington in the last four years compared to surrounding cities, like Fontana, which has seen more than 50 warehouses go up in the last decade under the leadership of Mayor Acquanetta Warren, one of the most vocal supporters of warehouse development among Inland Empire leaders. But Bloomington has still borne the environmental impacts of warehouses in neighboring communities.

Every census tract in Bloomington is in the 90th percentile or above for ozone pollution in California, meaning its ozone pollution is worse than at least 90% of census tracts in the state.

Bloomington, where 83% of the 24,000 residents are Hispanic, has endured as one of the few remaining rural pockets that straddle the 10 Freeway. The proposed warehouse project site is currently filled with ranches and farms. One property owner runs a plant nursery; another grows and sells giant palm trees.

While the poverty rate in Bloomington is considerably higher than the state poverty rate (19% compared to 11.5%), nearly 70% of the community’s residents own and live in their homes. Many have carved out a Mexican “ranchero” lifestyle. Horses share the roads with cars on Bloomington’s dirt-lined streets.

Numerous county planning documents over the years register the community’s wish to maintain this rural character.

To Carlos and members of Concerned Neighbors of Bloomington, a community group opposing warehousing, the proposed Bloomington Business Park is incompatible with that wish.

“I have no idea how developers can go to the county and put in an application for our homes that they have no right over,” Carlos said. “That’s the frustrating part. How it’s even allowed.”

A San Bernardino County spokesperson said the developer is allowed to propose the project even if it doesn’t yet own all the properties within the project zone.

“Proposing a project does not create any impacts on a community nor does it provide any guarantee that the proposal will move forward,” the county spokesperson said. “The burden will be entirely on the applicant to acquire the land necessary to execute the project.”

If the project does move forward, it wouldn’t be the first time that residential land in Bloomington is rezoned against nearby landowners’ wishes.

Thomas and Kim Rocha founded Concerned Neighbors of Bloomington in 2015 as an effort to halt the rezoning of an empty plot of residential land directly behind their house for the construction of a warehouse.

The County approved the project in 2018 and last year when an Amazon delivery center opened up in the new warehouse, the Rochas sold their “dream” home and moved to Nevada. Carlos, who lives just outside the boundary for the new 213-acre project under contention, took over leadership of the group.

A tabled state bill to reduce health risks from warehouses

Regional environmental justice groups like the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ) and the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice have backed local community efforts to halt this project and others like it in the region. They argue that projects like the one in Bloomington are examples of environmental racism because they’re proposed in mostly Hispanic communities.

The stream of diesel trucks visiting the warehousescreate ozone and particle pollution, linked to illnesses such as the development of respiratory diseases in children. And a recent study showed that warehouses are disproportionately located in low-income and medium-income communities of color.

“I’m here to simply ask you to lead with your heart,” said CCAEJ member Adonis Galarza to county supervisors regarding the proposed project at a meeting last year. “I think we have all been seeing the influx of warehousing in the Inland Empire. Our most vulnerable communities— communities of color— are suffering the most. Our health is the worst.”

The environmental justice movement that has formed against warehousing in the Inland Empire has found allies in Sacramento.

“If we contemplate what it really means, it will make you cry just to think of those poor families, those children, those teachers,” said California Assembly Majority Leader Eloise Reyes, who represents Bloomington and large parts of the Inland Empire. “The fact that we are saying that they are unimportant.”

In March 2021, Reyes introduced a bill that would impose more stringent requirements on warehouse projects, including a 1000-foot buffer zone— slightly more than three football fields — between project boundaries and sensitive areas like homes and schools. It would also require developers to commit to implementing a plan to transition to zero-emission trucks, among a suite of other measures.

The bill, which was tabled earlier this year, has received little support from local leaders.

“Cities want to decide for themselves; counties want to decide for themselves,” said Reyes.

The Bloomington Business Park project would fail to meet the buffer zone requirement of Reyes’ bill.

A parallel fight in Fontana

As globalization sent blue-collar manufacturing jobs overseas in the 1980s and 1990s, political and business leaders in Southern California invested heavily in a logistics industry that could support the new flow of manufactured goods from Asia, said University of Southern California professor and geographer Juan De Lara, who provides a history of the Inland Empire’s logistics industry in his book Inland Shift: Race, Space and Capital in Southern California.

“They knew there wasn’t enough land in Los Angeles County,” explained De Lara. Comparatively, land in the San Bernardino and Riverside counties was cheap and abundant, making it an ideal place to build warehouses. Leaders started supporting heavy spending on infrastructure like rail, off-ramps and grade separation in the area, De Lara said.

In recent years, Fontana representatives have pushed back against warehouse regulations like the ones in Reyes’ bill in the name of protecting jobs. “What we need to discuss is ensuring that cities can retain the ability to establish land use policies that are appropriate for the local area,” Mayor Warren told the Fontana Herald. “We don’t need one size fits all mandates from Sacramento that will eliminate jobs and force Fontana residents to go elsewhere for work.”

In July 2021, Attorney General Robert Bonta sued the City of Fontana for its approval of a warehouse project that shares a boundary with Jurupa Hills High School. Bonta alleged that the project violated procedures laid out by the California Environmental Quality Act, a decades-old state law that mandates an environmental impact study for new projects. Twenty warehouses have already been built in the area around Jurupa Hills High School, according to the Attorney General’s office.

A group of Fontana residents called the South Fontana Concerned Citizens Coalition collected more than a thousand signatures in an online petition last yearto appeal the approval of the project. They demanded more commercial development — like retail and grocery stores — instead of industrial development in the city.

Fontana and the attorney general’s office reached a settlement earlier this month. The project will move forward, but the developer will pay $210,000 to a community benefits fund and Fontana will adopt what Bonta called the “most stringent warehouse ordinance in the state.” The ordinance requires new warehouses adjacent to sensitive receptors like homes and schools to include a 10-foot buffer zone. Still, the buffer zone is exponentially smaller than the one called for in Reyes’ bill.

Southern California’s air quality regulatory agency announced this month plans to update the guidance in the California Environmental Quality Act to consider existing air pollution in environmental impact reviews of new projects.

“Doing nothing is not an option”

In Bloomington, some residents accept the incoming industrial development despite its proximity to homes and schools.

Cheryl Garnder lives in a house inside the Bloomington Business Park project zone.

If you ask Garnder, Bloomington is already surrounded by warehouses in neighboring cities, trucks already congest the streets, and the air pollution is already bad. She thinks the town might as well reap the economic benefits of a seemingly inescapable industry and give residents the opportunity to sell their properties for a handsome price. Gardner said she hopes to sell her property to the developer.

A similar argument has been made by members of Bloomington’s Municipal Advisory Council, which serves as a liaison between the San Bernardino County board of supervisors and the community of Bloomington.

I ask my county board members, ‘Where are you? Why haven't you protected us from this?’Bloomington resident Benjamin Granillo

Its longtime chair, Gary Grossich, said the council moved to open Bloomington up for industrial development in 2017, citing the fact that Bloomington was running a deficit and lacked basic services like sewage and police.

“Doing nothing is not an option, because, in reality, the community has been deteriorating for quite a period of time and it’s become a magnet for unpermitted uses,” Grossich said, pointing out that many residents have used their large plots of land to operate illegal truck yards.

The advisory council hasn’t welcomed all logistics development in Bloomington. Last year, it sent a letter to Bonta’s office asking him to look into two controversial trucking facilities approved by the county board of supervisors. Grossich told the San Bernardino Sunthat the projects would have worse impacts than the Jurupa Hills High School warehouse in Fontana.

Grossich believes the Bloomington Business Park can potentially generate the kind of revenue that can help set Bloomington on the path toward incorporation as a city.

The project is currently under environmental impact review before it goes to the county planning commission for a vote. If the planning commission approves the project then it goes before the county board of supervisors who will make the final vote on whether to rezone the land and greenlight the project.

Still, many residents feel ignored by the advisory council and the country board of supervisors, which ultimately make decisions for the community.

Hundreds of Bloomington and nearby residents signed their names to letters to the county expressing concerns or opposition to the project. Alongside concerns about increased air pollution, some discussed the danger truck traffic poses to children walking home from schools, especially in Bloomington where many streets lack sidewalks.

“It is time to put a stop to Orange County & L.A. County developers out to destroy the Inland Empire with countless warehouses only to line their pockets leaving us with truck traffic and pollution,” wrote Bloomington resident Benjamin Granillo in a letter to the county. “I ask my county board members, ‘Where are you? Why haven't you protected us from this?’”

Granillo’s parents bought a two-acre plot of land in the project zone more than 40 years ago and built their own ranch-style house on the property. On some weekends, the Granillos sell ripe avocados from their tree out of a small shack near the edge of their property.

A number of their neighbors have already agreed to sell their homes to the project’s developer, but Granillo said his family is holding out. They intend to hang on to what they worked hard to build.

On a recent Sunday, Granillo’s mother stood out by their avocado shack and pointed east to the ridgeline of the San Bernardino mountains, lamenting the thought that what could soon greet her instead is the mute wall of a warehouse.