Warehouses Pave Over Historic Dairy Lands in Ontario and Chino

In 1976, my parents bought a three-bedroom home in Chino at the western edge of San Bernardino County. The idea was to escape growing neighborhood gang violence in the Los Angeles Crenshaw area and halve my father’s 40-mile commute to Anaheim. The new house sat on a sprawling lot of over an acre, surrounded by other homes and horse stables. Remnants of former orange groves and ranching still characterized the area. My parents were going to live the “country life:” grow vegetables, raise chickens and tend fruit trees, especially when my father retired in ten years.

Unfortunately, that dream did not play out. My parents fell prey to industrial development and were pressured into selling their property. The home they had purchased was north of Riverside Drive, on unincorporated land, close to the Pomona (60) and Corona (71) freeways: developers targeted this area for industrial business parks. Although some of the last holdouts, my parents eventually caved, accepting the seeming inevitability of development. They abandoned their dream and moved back to Los Angeles to be closer to friends and family — less than two years into my father’s retirement.

What my family experienced over 30 years ago was just the start of a massive transformation of the Inland Empire. Because of its proximity to the ports of Long Beach and L.A., the Inland Empire became a transportation hub during California’s citrus heyday and then during World War II. But the infrastructure built then pales in comparison to what came after. According to data from the Robert Redford Conservancy, the number of warehouses in San Bernardino and County has grown from 24 in 1975 to 3,176 in 2021, paving over 23 square miles of the county. That is equivalent to 82 percent of the City of Chino, or over half of the area of neighboring Ontario.

As a teenager trying to escape the monotony of suburban life, I remember taking marathon bike rides from the northwest corner of Chino, heading east, through miles of open land, crossing unpaved roads lined with eucalyptus trees and smelling the sharp aroma of cow manure. Now, housing developments and business parks dominate the landscape until you cross Euclid Avenue (83) into the City of Ontario, where a few dairies and farms survive. This area, formerly a dairy preserve, is ground zero for a battle to preserve and reclaim land from warehouse development.

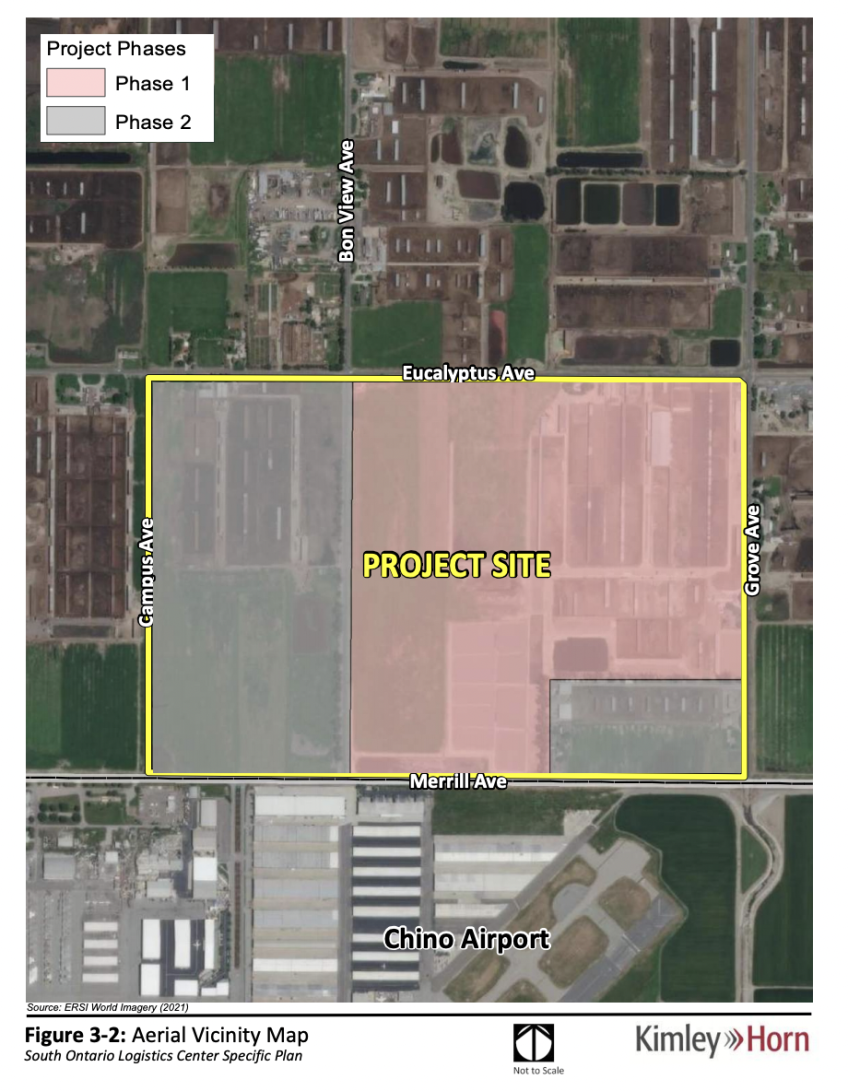

The land in question is 219.39 acres of Ontario agricultural fields, where the South Ontario Logistics Center Specific Plan has been proposed. It is part of what locals call the “donut hole,” approximately 4,000 remaining acres of open dairy and farmland in the middle of encroaching urban development. Most of this land is made up of former dairies that have already been bought out, and it also includes some land under conservation easement, so-called Prop 70 lands, that were supposed to be protected with state bond money as agriculture in perpetuity.

Residents, including environmentalists, urban farmers and local civic groups, are fighting against the South Ontario Logistics Center Specific Plan, demanding that Ontario evaluate more sustainable land-use possibilities, given the air pollution and local health impacts of warehouses, as well as climate change concerns. They want the City to consider an alternate vision, which would halt rezoning, set aside farmlands for small-scale farmers, and initiate the reclamation of former dairy lands contaminated by nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide from years of cow manure.

Farmers like Randy Beckendam, of the Southern California Agricultural Land Foundation, want the City to consider support for local food systems, the importance of which were highlighted during COVID-19 supply chain disruptions.

The history of the San Bernardino County Dairy Preserve

The “donut hole,” the last remaining open land in Ontario and neighboring cities, was legislated as a conservation district in the 1960s. In the 1950s, mostly Dutch but also Portuguese and Basque dairymen settled in Chino and Ontario after being incentivized to sell out their Artesia, Cerritos and Paramount dairies to suburban developers. In 1967, under the 1965 Williamson Act, 17,000 acres were designated as the San Bernardino County Dairy Preserve. The law gave considerable tax breaks to property owners who agreed to restrict their land to agriculture for at least ten years, but the land was not protected in perpetuity.

In the initial years, dairy farmers who were part of the preserve thrived. The region produced most of Southern California’s milk and during its heyday, in the late 1980s, the preserve was home to over 400 dairies and 350,000 cows, the largest concentration in the US.

Dairy is a highly polluting industry, and as toxic waste from cows accumulated on the land, farmers could see that implementing cleaner practices would start to impact their profit margins. Dairy waste made these lands undesirable for home development, and city planners in San Bernardino and Riverside saw huge revenue sources that could be “milked” through mixed-use development, literally paving over the dairy stench to make way for the logistics industry. As dairy operation costs and property prices rose, developers lured farmers to sell, and San Bernardino County officials decided to break up the preserve, allowing dairy farmers to withdraw from their contracts early and cash out their lands.

In 1986, Jerry Blum, current director of the Ontario Planning Department said, "In its truest sense, this is a brownfield — about four feet thick! … Our point was, let's build the hell out of this place because it's the doughnut hole. It's surrounded by urban uses. It's not habitat for anything.”

Meanwhile dairies moved to cheaper lands in Tulare and Merced counties, continuing the cycle of dairying on cheap land and then selling to developers for high prices.

In 1999, the City of Ontario annexed 8,200 acres of former dairy preserve land. In 2003, the City of Chino annexed 5,300 acres while Chino Hills annexed the remaining few hundred acres. In 2002, Chino Mayor Eunice Ulloa announced a 5,226-acre master plan called “The Preserve at Chino,” developing much of the city’s newly-acquired dairy preserve land into a mixed-use landscape of homes and industry.

Paving over Prop 70 conservation lands

In 1988, as the dairies were starting to sell, then San Bernardino County Supervisory Larry Walker received 20 million dollars of Prop 70 funds, state bond money set aside to rehabilitate and protect natural lands supporting unique or endangered species and to place them under conservation easements in perpetuity.

The Southern California Agricultural Land Foundation was founded to manage 350 acres of former dairy lands in Ontario that were purchased with the Prop 70 funds. However, these agricultural lands were not placed under conservation easements and development rights were never retired, as required by the state. Some of these Prop 70 lands are part of the area that is currently under consideration for the South Ontario Logistics Center Specific Plan; farm conservation advocates describe the potential sale of these lands as a violation of public trust.

If the plan goes through, it wouldn’t be the first time Prop 70 lands in the Inland Empire have been purchased and developed for warehouse use. J & D Star Dairy, one of Chino’s last remaining large scale dairies, sat on land leased from San Bernardino County, which auctioned off these lands in 2014. Developers snatched up the dairylands for over 65 million dollars. The dairy shut down in 2018, and now a massive parking lot and Fedex-Chino warehouse lie at the corner of Merrill and Flight avenues where hundreds of cows used to moo and graze.

Developers have also been chipping away at the former farmland adjacent to the Chino Airport, buying out dairies, cleaning up contaminated water supplies, pushing for rezoning and building warehouses. Dairy farms that stretched from the airport in all directions have been replaced by warehouses, including Amazon, Nike and Fedex. At the Watson Industrial Park, Chino — part of Chino’s “The Preserve” development — all that remain are bronze cows, grazing on warehouse lawns.

The fight against the South Ontario Logistics Center

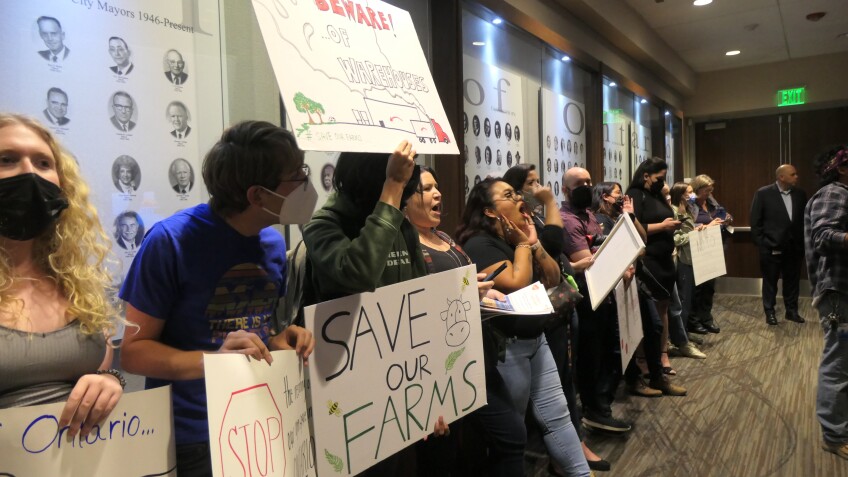

At a March 1 Ontario City Council meeting, residents voiced opposition to the South Ontario Logistics Center Specific Plan, urging members of the City Council to vote “no” on a General Plan to amend zoning. A coalition of environmental and resident groups insisted that the City consider the well-being of residents who are already fed up with growing air pollution and traffic congestion from warehouses. They gathered over 1,000 signatures in an opposition letterthat outlined their concerns and urged the City to consider the current climate crisis.

Many at the meeting pointed out how the city council has aligned with developers, anticipating higher tax dollars generated by industrial uses. During public comments, Andrea Galvan, who grew up down the street from City Hall, said, “The City is evolving in a way I didn’t expect. I’m here today like many of my neighbors to voice opposition to taking away farmland to allocate for warehouse industrial use….We live somewhere special, and you would give that up for short term tax revenue?”

Lifelong Ontario resident Angela Miramontes argued that while warehouses do create jobs in the short term, the jobs are low paid, and not worth the cost of increased air pollution and ongoing greenhouse gas emissions that warehouses entail. “We and you need to think about more than money,” she told the council.

Labor unions including Ironworkers 416 and 433, Plumbers, Steamfitters Union Local 398, and Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA) showed up to support the project. Ralph Velador of LIUNA said, “We have partnered with the developer because their core beliefs of well-paid benefit construction jobs with health care and pensions mirror ours.”

After public comments, City Council Member Debora Dorst-Porada defended the city’s position, noting that the city was not making anyone sell their land. "They’re selling their land because they want to for whatever reason they want to….It’s difficult these days to operate a dairy and be successful," she said.

Despite the feisty opposition, the City Council voted unanimously in favor of the logistics plan, siding with developers and labor constituents who would benefit from short term construction jobs.

The current fight against the South Ontario Logistics Center is not over. The Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, an Inland Empire environmental justice organization, is suing the City of Ontario over what it claims was a fast tracking of the project’s environmental impact review and failure to give proper time for community input.

The opposition attempted to gather 10,000 signatures for a referendum campaign that would override the city council's ordinance and allow Ontario residents to vote on the logistics center plan, but they weren't able to collect these by May 2. They are now strategizing next steps to put pressure on the City.

An alternate vision of a sustainable food system

The coalition opposing the logistics center plan includes the Pitzer College-based Robert Redford Conservancy, the Southern California Agricultural Lands Foundation, the Sierra Club, Inland Valley Advocates for the Environment, the League of United Latin American Citizens and many other non-profit and civic groups. They are urging the City of Ontario to retire the development rights on all Prop 70 lands in the City and place them under permanent conservation easements.

Instead of warehouses, these groups envision a future master plan for the 4,000 acres of “donut hole” lands that could include reclaiming and restoring dairy lands and creating space for community food gardens. They are encouraging the creation of land trusts for food-producing nonprofits, which would support farmer training, biodiversity and community health.

Models include the flourishing Huerta del Valle community garden in Ontario and Jurupa Valley and Just Plant It, a non-profit in San Bernardino; both provide organic produce in food deserts. The coalition is also exploring net-zero housing models that combine lower and median density housing with agriculture.

My own family's story, like so many in the area, ended with us selling our land. These residents and advocates are fighting to change the narrative that rampant industrial development is inevitable; they are helping to rewrite the story of this area. By bringing environmentalists, farmers and other residents together, they hope to reclaim lands for more healthy and sustainable uses.