The Transgressive Act of Holding Hands on the River

Over the past few months, the Los Angeles River has been a political issue. It has been the center of debates about social equality, health, and fiscal feasibility. The Los Angeles River has been so buried in these laden terms that it's easy to forget this waterway is first and foremost a place where real people gather, where they seek shelter legally or illegally, where residents come to simply commune with others.

Artist Paige Tighe seeks to reorient the experience of the Los Angeles River by the simple yet powerful act of holding hands. Her "Walk with Me" series on the Los Angeles River was made possible by Play the L.A. River, a collective of river enthusiasts looking to increase awareness and accessibility to the river by engaging people in fun activities.

Over the course of a week, Tighe, a Minnesotan who used to live in Los Angeles' Mar Vista neighborhood, asked anyone willing to walk with her on the banks of the Los Angeles River. Not only will they be walking, but Tighe's process specifically requests that Tighe and her companion walk while holding hands.

More art and activism along the L.A. River

It is the last phrase that always gives people pause. I know, because it did me. As I read through Play the L.A. River's description of the event. Would I be comfortable holding a stranger's hand? Will my hands get too sweaty? What would it feel like to feel the unfamiliar contours of an unknown? It turns out, the experience was surprisingly freeing.

Tighe and I met at the Valleyheart Riverwalk between Fulton and Coldwater Canyon, a space that I've always admired because it represented the hard work and dedication of so many neighbors to revive their piece of Los Angeles. If nothing else, the history of the place and its transformation would be meaningful to me during our walk.

As I alighted the bus, walking toward the Riverwalk, I experienced a few more minutes of trepidation. We are all trained to protect ourselves, to stay within our comfort zones. The prospect of holding an anonymous hand seems in violation of all those instincts, but as I crossed the road, I also crossed a mental checkpoint. I had already signed up and I would follow through.

Tighe turned out to be a petite lady, much like me. That day, she telegraphed the vigor of Los Angeles with a hot pink top, blond pixie cut, and speckled pink sunglasses. She called our linking hands "an exchange of energy." Rather than expect her to lead, she let me take the reins, leading her where I felt. With her hand in mind, we wandered the well-maintained paths of the Riverwalk, past joggers, pedestrians, and pet owners. We meandered past blossoms and passed by the occasional piece of rubbish -- a reminder of the Village Gardeners constant battle against disarray along the river.

Tighe is no stranger to holding hands. She has been conducting her "Walk with Me" sessions for almost three years now. A graduate of Otis College of Art and Design with a Master's in Public Practice, Tighe has always been interested in art that involved another. Before holding hands, she danced in public buses and sang pop songs with strangers. Her work is all about drawing ourselves out of our usual solitary state.

The idea for "Walk with Me" first began with a Burke Williams Day Spa session. "I was laying down and warm water was being sprayed all over my body," Tighe writes on her successful Kickstarter page for an East Coast tour of "Walk with Me," "As this woman massaged my hand, all I wanted to do was hold her hand. Not out of romantic desire but a desire for connection."

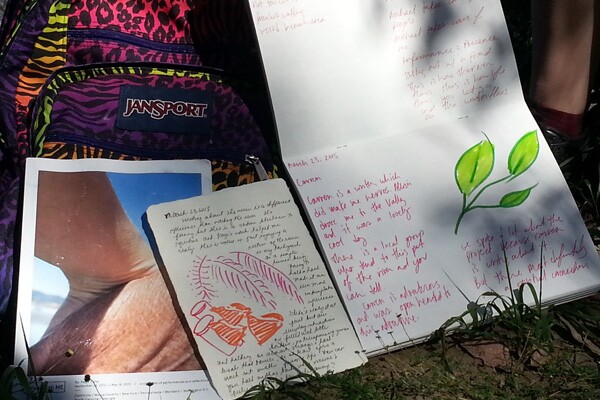

That need pushed Tighe to reach to friends, first on Facebook, asking to hold their hand. Surprisingly, people wanted to do the same. It's as if a shared light turned on, by writing down her need to be held, other people also realized their own loss. In the next months, Tighe walked with people, held their hands, took photos, and wrote down their thoughts. She even took her show on the road to the East Coast, traveling nine cities in three months. At the end, she produced an artist book about the experience.

Tighe came to realize that "Americans don't touch each other very much and I reflected that touch was not a part of my daily life either." A study by psychologist Sidney Jourard in the '60s showed that English friends would never touch each other during a conversation over coffee. Americans did slightly better by touching at most twice in an hour during a rare burst of emotion. But in France, the number shot up to 110 times per hour. And in Puerto Rico, those friends touched each other 180 times.

Yet touch is such an important part of life. Dacher Keltner of UC Berkeley's Greater Good Science Center writes, that touch is "far more profound than we usually realize: They are our primary language of compassion, and a primary means for spreading compassion."

In that hour holding hands by the river, I could understand why this was so. Tighe and I exchanged thoughts of the river, impressions of the waterway as two people would. We didn't view the river as a mere political platform or an issue to be tackled. Our walk humanized us and opened us to the gushing life on the river. Tighe's walks along the river seems to have the same effect on others. It encouraged them to see the river as a catalyst to one's own creativity and a way into one's own humanity.