Standing Rock: Art and Solidarity

Last summer and fall, we at the Autry Museum of the American West were in the final months of preparing a large exhibition, California Continued, about California Native peoples and the environment — a companion project to KCET’s show Tending The Wild.

Meanwhile, in a different corner of the West, the camps of the Standing Rock water protectors — as those hoping to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) called themselves — began to receive widespread attention. As far as California is from Standing Rock, many of the issues Native peoples face in each place are parallel. Historical dispossession still affects Indigenous peoples; sacred sites are being destroyed; clean water is a precious and sometimes endangered resource; and tribes remain resilient and resistant in the face of these challenges.

A number of the museum’s California Native advisers began traveling to North Dakota in solidarity with the NoDAPL movement. It seemed that the Autry — a museum trying to maintain and develop strong relationships with the Indigenous communities represented in our collections, and seeking to tell stories relevant to those communities — had a responsibility to reflect on the events capturing such wide attention across Indian Country and beyond.

This sparked our proposal to mount a quick-turnaround (by museum standards) mini-exhibition, Standing Rock: Art and Solidarity, which opens Saturday, May 20.

What can a small museum display add to the already vibrant dialogue that these events have inspired? As a cultural history institution, the Autry is not the best venue to detail the probability of a pipeline leaking or the economics of oil. But we are poised to demonstrate the “shared cultural heritage of the Lakota nations and all people,” as the American Alliance of Museums put it in a statement last fall, and to stand against the destruction of sacred cultural sites. We can also place these news events in the context of much deeper histories. And we can offer visitors the opportunity to stand in the presence of artworks and artifacts that convey the energy of the movement and the profound questions it raises.

Something historically significant occurred at Standing Rock. The artist Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan/

“What was happening at Standing Rock that was most amazing to me was the solidarity formed by different culture groups coming together to support one another and to look out for one another.”

Indigenous people from around North America and around the world, joined by non-Native allies, traveled to rural North Dakota or otherwise supported the water protectors. Intertribal solidarity is nothing new, but at this scale it may be unprecedented. Zoë Urness (Tlingit/Cherokee), who lent four powerful photographs to this installation, also noted the spiritual significance of the movement: “Belief in the spiritual workings from ancient times is a weapon that doesn’t need violence to win.”

The environmental movement, which has too often ignored or disparaged Native perspectives, recognized Native leadership in a new way. And these alliances, while not without their difficulties, gained public and media attention for a Native American-led movement to a degree not seen since the 1970s “Red Power” era.[1]

Of course, part of that attention sprang from the violent responses of security and law enforcement. While the violence was shocking to many non-Native observers, many Native people I have spoken with were outraged, but not surprised. As most of us know in general terms, American history holds a long trail of violence against Native peoples. Looking at those histories more closely, it is remarkable how often that violence accompanied natural resource extraction.

In the book The Last Indian War, about the Nez Perce struggle to retain their territory in the Northern Rockies, the historian Elliott West makes this astute observation: “With few exceptions, every major Indian conflict in the far West between 1846 and 1877 had its roots in some gold or silver strike.” West enumerates the violence that followed the California gold strike of 1848 (which led to out-and-out genocide), the Colorado strike of 1859 (which led to wars on the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples, including the Sand Creek Massacre), the Arizona strike of 1863 (leading to wars on Apache groups), and the two strikes, in Montana and South Dakota, that led to wars with Lakota peoples in 1868 and 1876 (including the Battle of Little Bighorn). Even Cherokee removal and the Trail of Tears were preceded by a gold rush in Georgia in 1829.

With this in mind, it is hard not to see the Bakken oil boom of the past decade as today’s gold rush, with a familiar mix of economic opportunity and social-environmental upheaval. The Standing Rock movement, too, is part of a long lineage—a lineage of protectors, or a lineage of obstructions to great fortunes, depending on your perspective. The Autry tells some of these histories in other galleries, and we have tried to place the recent events in context through a self-guided “Sovereignty and Struggle” tour we produced in association with Standing Rock: Art and Solidarity. This context may help visitors understand the painful echoes and the real threat that the pipeline represents for many of the Indigenous activists (and non-Native allies) who felt such solidarity to, as the T-shirts say, “stand with Standing Rock.”

We must not oversimplify things, and a museum display may run some risk of doing so. Many Native people in fact favor energy extraction as a means of developing economic and political sovereignty. The Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara Nation has taken part in the Bakken boom; others from Oklahoma to Montana have pursued oil, gas, coal, and other fossil fuels over the past century. Often, unscrupulous and even murderous outsiders have sought to exploit these tribes’ relatively weak political position to siphon off much of the wealth.

There is a long-running stereotype of Native peoples that paints them as preternaturally ecological, most obviously exemplified by the “crying Indian” of the 1970s TV commercial, played the Italian-American actor who re-christened himself Iron Eyes Cody. (Cody married the Seneca/Abenaki archaeologist Bertha Parker, and they were active in the Los Angeles Native community—they both contributed to the Autry and historic Southwest Museum collections, now merged in the present Autry Museum.) We have tried to avoid using the water protectors as ecological PSAs by simply presenting their work and their words, but as Melanie Benson Taylor put it in an important recent essay, “the line between comradeship and co-optation is frustratingly dim.”

"The line between comradeship and co-optation is frustratingly dim."Melanie Benson Taylor

Demian DinéYazhi´ (Diné), another artist who contributed work to this exhibition, offered these thoughts on making sense of the movement growing out of Standing Rock: “Moving forward, we must collectively ask ourselves how this revolution will work, continually address our methods of resistance and decolonial praxis, and honor our relationship with the land as a sacred communion interwoven with our will to survive.”

From the museum’s side, our job is not to promote or impede this “revolution,” but we do need to engage in our own “decolonial praxis.” This may be unfamiliar terminology — I understand it to mean a way of acting every day in our work and life that acknowledges the painful history of colonization on this continent, and seeks to remediate (even in small ways) the damage that history has caused, for peoples both Indigenous and non-. Adding a “from the headlines” space to our galleries hopefully accomplishes one small step in that ongoing “praxis” and continues our broader exploration of the many intertwined stories of the American West.

[1] Sherry Smith’s excellent history, Hippies, Indians, and the Fight for Red Power (2012), shows how a similar series of sometimes awkward and problematic alliances in the 1960s and ’70s nonetheless accomplished real progress for Native self-determination.

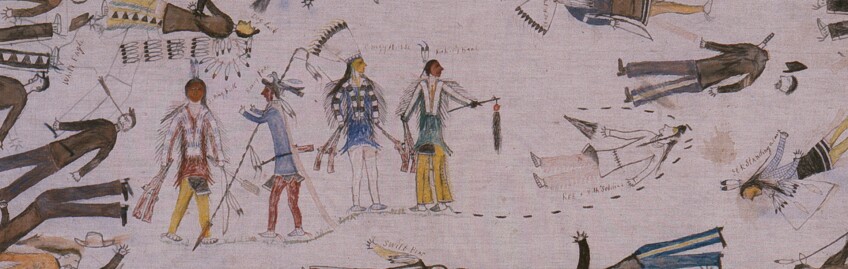

Banner: Detail from Kicking Bear (Lakota), "Battle of the Little Bighorn," circa 1896. Southwest Museum of the American Indian Collection, Autry Museum.